Reviews

Solomon Islands: an untainted Pacific Island culture with wreck dives at World War II battle sites

From the Air Nuigini flight out of Port Moresby, the horizon separating the deep blue sea from the deep blue sky is virtually invisible. There are a few cotton clouds as if drawn by a child having fun, and occasionally there are dotted islands as if set there by a Creator having a particularly happy day. Welcome to the Solomon Islands, which here in the South Pacific are usually just passed over on the way to even more glamorous destinations. Yet for the most intrepid visitors, there awaits an authentic culture almost untainted by tourism, along with many Second World War wreck dives.

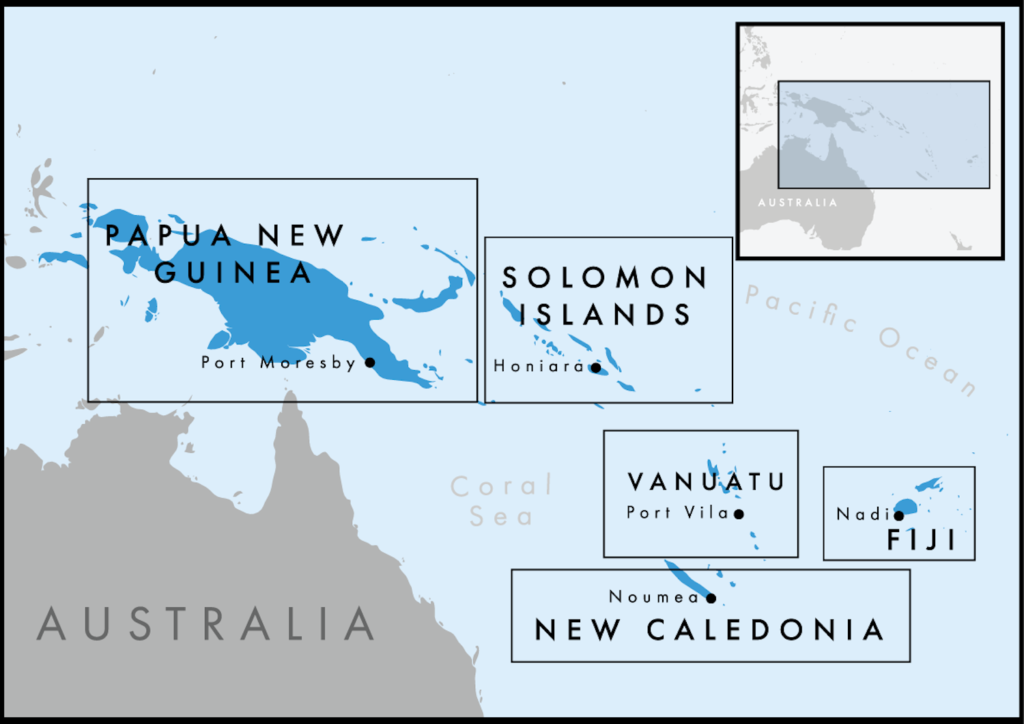

There are just six major islands; 992 in total, of which 347 are inhabited. Part of Melanesia, to the east of Papua New Guinea and its dependent territory the North Solomon Islands, they are spread over 28,000 square kilometres. They are mostly volcanic, with dark sand, and covered in tropical rainforest, though ravaged by logging.

The Solomon Islands were first settled 4,000 years ago by Melanesian people. They were a British Protectorate from 1893. At the end of the nineteenth century slaves were stolen away to work in the sugarcane fields of Australia and Fiji. In 1942 they were the site of a crucial American battle with Japan in World War II, hence the large number of wrecks to dive. Independence came in 1978 along with the local dollar currency. At the end of the twentieth century ethnic tensions between peoples from the two main islands in the centre of the country, Guadalcanal and Malaita, flared in civil war.

It is politically stable these days, though there are concerns about human rights abuses and homosexuality is illegal. It feels remote, isolated, and something of a backwater.

The population is just over 650,000, with 10% in the capital Honiara on Guadalcanal. More than 95% are Melanesian, mostly very dark skinned, many of whom cling to ancient customs and village life. There are about 90 local languages, though business is official conducted in English, which is widely spoken along with Pijin, a slave trade development. The land is mostly owned by tribal leaders, which deters foreign investment but permits the exploitation of precious raw materials, notably trees, the country’s main economic activity. Some 65% of these exports go to China while less than 1% go to nearby Australia, which clearly illustrates the extent of Sino influence in the region. There is very low mobile phone penetration and very poor connectivity throughout the country though there are hopes that the long-promised Coral Sea cable link to Papua New Guinea might actually open sometime in 2020. And 95% of people are Christian; you will see colourful churches in every poor village and you are likely to find a Gideon Bible in your hotel room drawer.

The country claims as many as 25,000 tourists a year, which they hope to double by 2025. But we saw no more than half a dozen when we were there for a week in August, which is a good time to go given it is both balmy – daytime 27°C, nighttime 23°C – and dry. There are two rainy periods to be avoided: from February to May and from September to November.

In these parts they say “west is best”, by which they mean in the Western Province, particularly around Gizo and Munda, there is a smattering of more conventional tourist resorts. The appeal is some good sandy beaches, decent surfing on waves of up to 2m, game fishing charters for marlin and tuna, and several renowned dives (particularly the Toa Maru, a 140m Japanese freighter, and the Grand Central Station Reef).

You can get to the Western Province on a one hour flight with Solomon Airlines from Honiara. There are also a handful of private companies operating all sizes of ferry. And of course you can yacht, but you will need to agree mooring rights in advance with local tribal leaders, to whom you will have to pay variable rates of kastom fees.

However, most of these attractions are bettered in other parts of the South Pacific. So the principal interest in coming to the Solomon Islands is to get a feel for a relatively unmodernised community life, and to visit historic Second World War sites, especially underwater, and that is all best found in the central islands of Guadalcanal and around.

Most people enter the country at the airport fifteen minutes east of Honiara on the north coast of Guadalcanal. We were the only Westerners on our two and a half hour flight. You get your passport stamped by officials wearing fabulously lurid shirts, typical of the Pacific Islands, which sets an appropriately relaxed tone. The airport is not the most modern and you are well advised to check ahead of departure that your ticket has been processed correctly. Leaving the airport, take the tarmac road into town by cab or pre-arranged pick-up, probably blaring reggae or country music, past blokes playing football on full-size pitches without shirts or shoes.

It is immediately apparent that Honiara is gritty and authentic. For example, the pavements, where they exist, are splashed with red stains despite the numerous signs requesting people not to spit the ubiquitous betel nut that also tints their teeth and gums.

In the Central Business District near the harbour you will find the four main hotels in a line by the Pacific Ocean: the Solomon Kitano Mendana Hotel, a pleasant boutique; the Heritage Park Hotel, host of the British High Commission, proud base of William and Kate as displayed in photographs on the walls, and home of an excellent open-air bar right on the sea called Splash; the Coral Sea Hotel & Casino, where the minimum bets are as low as €1; and the IBS Monarch Hotel, which has a very good bar and grill attached.

Along the coast road back towards the airport, plied by numerous white van buses, there are dozens of ersatz shops selling electronics, kitchenware, balls for various sports, flip flops, T-shirts, and second hand clothes. Some have Chinese names, many have local youth lolling in the displays, and all have security guards sitting on high chairs at the doorway. Close to the harbour there is a tailor specialising in over-night made-to-measure Pacific Island shirts. Nearby is the Central Market, under one large roof, where lines of sellers sit amid their fruit and fish; this is also where villagers from remote islands come to take cash in exchange for rare shells and teeth stripped from dolphins, which are used as barter and dowries to pay what is known as a ‘bride price”.

The best place to begin to understand the Solomon Islands is at the impressive American War Memorial, high on a hill with great views back over the town and out across the ocean.

Exploiting their successful December 1941 attack on Pearl Harbour, Japanese planes soon struck at American, British, Chinese and Dutch territories across the Pacific. By spring 1942, the Japanese were threatening Australia from the Solomon Islands, building an airfield on Guadalcanal and taking Tulagi, the former capital, amid the neighbouring Nggela or Florida Islands, 40km to the north.

The tide began to turn in the Pacific at the Battle of Midway in June 1942, so in August US forces landed on the Blue Beach in Tulagi, the mainland of Guadalcanal, and the tiny island of Savo in the channel between them. Liberation took six months and this water subsequently became known as Iron Bottom Sound because of the vast amount of military hardware – ships and planes – that were downed there. That is why this is a site of world importance for wreck divers.

The American Memorial itself is very dignified. As is the Japanese Memorial on a nearby hill; the white towers in front of the setting sun is a beautiful sight.

To get there, take an unmetered taxi (get one by the hour for SI$100 or €10) for ten minutes up the hill past lines of market stalls, the circular National Parliament on Hibiscus Avenue, to which you can take tours, and the National Museum on Mendana Avenue.

We arrived late in the afternoon, only the second visitors to sign in that day, though a handful of locals also lounge about. The Florida Islands are clearly visible towards the horizon, and in the foreground among palm forests stilted houses of wooden walls and corrugated roofs are propped against the hills on both sides of the valley. Smoke floats from indoor fires up through chimneys, flooding our nostrils with lovely smells of cooking food. Sounds rise of children playing football and choirs singing in church.

The best wreck diving in the world is at Chuuk in Micronesia, also in the Pacific Ocean. That is because the reef enclosing Truk Lagoon has beautifully preserved the vast Japanese fleet sunk there during WWII. Although there are similar numbers of huge ships and aircraft haunting Iron Bottom Sound, the channel between Guadalcanal and Tulagi is open sea, so the tides have disturbed the wreckages, turning many on their sides, sweeping away their cargo and artefacts. That said, there are lots of them and many are worth investigating.

In a sign of the scale of tourist interest here, there are fewer than half a dozen dive shops throughout the whole of the Solomon Islands. To get at Iron Bottom Sound you need to use either Tulagi Dive, near the Yacht Club at the harbour in Honiara, or Raiders Hotel & Dive, on Tulagi itself – though neither of them had a functioning boat while we were there – or one of the two liveaboards, both of which operate from Honiara: the Bilikiki and the Solomons PNG Master.

Several of the best wrecks can be reached from the shore. For instance, just 12km west of Honiara, but taking well over half an hour in a truck along the pot-holed main road, is scruffy Bonegi Beach. This is hailed as the best beach on Guadalcanal, and you have to hand over SI$50 to a couple of kids at the shack on the way in for upkeep, though they clearly do not over-exert themselves in clearing the rubbish and picking up plastics. Within 10m of the beach are two big sunken ships: the Hirokawa Maru, a massive freighter known as B1, from which fled more than 2,500 Japanese fighters, though every single one was killed as soon as they made land; and the Kinugawa Maru, B2, a smaller transporter, which breaks the surface around the corner.

A little further west at Domo Beach there is the front half of a mammoth B17 Flying Fortress lying in clear shallow waters and smothered in fishlife. And on the west tip near Cape Esperance off the town of Tambea, about an hour and a half from Honiara, there is a 100m long I-1 Japanese submarine with a very storied history: it is because this vessel was hit and salvaged that the Allies were able to crack the Japanese wartime code, revealing the flight plans of Marshal Admiral Yamamoto, enabling the Commander-In-Chief of the Imperial Navy to be shot down in a major blow to Japanese morale.

On the other side of the channel are the Florida Islands, a chain of 50-odd small islets, one of which is Tulagi. Tulagi, just 5km by 1km, was the capital of the British Protectorate from 1896 to 1942, chosen for its relative lack of disease and its gorgeous views. Today, there are three cars and three trucks on the island of 2,000 people and it is the other good base from which to access Iron Bottom Sound. There are two more wrecks near the shore here: USS Kanawha and USS Aaronwarno.

There is talk of a ferry but nobody seemed to know if it is currently running. In any case, the fun way to get across is to wander down to the harbour in Honiara where you will find 20 or 30 red and blue small speed boats. Just talk to any one of the blokes hanging about there and negotiate a price for where you want to go, usually with extra sleep-over, return trip and gas costs; ours was SI$1,200 all-in.

At Raiders Hotel & Dive on the crescent bay, Bob and Eve can fix you up not only with diving, but boat tours of the Florida Islands and walking tours of Tulagi. There is not much to see but you’ll find a great atmosphere and get an inside view of local life. They also have the best dive shop T-shirts I’ve ever come across, splashed with local colour in the typical manner of the Pacific Island shirt. We were the only ones staying at the time.

A good metaphor for the recent history of the Solomon Islands is the site of the old British Governors’ No 1 House on Tulagi. Sited here for its tremendous views from the top of the highest hill back over the blue sea towards Guadalcanal, abandoned to the Japanese, won back by the heroic Allied invasion, then more or less forgotten about ever since.

The Solomon Islands are not the most fashionable destination in Melanesia, but they are certainly worth a look the next time you are passing through the region.