“Why have you come here?” our guide asks us within minutes of meeting. “People usually tell me they come here only when they run out of other countries to go.”

Well, we have been to more than our fair share of countries, for sure, but we have plenty of places we still want to visit. So, it was not for that reason.

We came to (Outer) Mongolia to experience the land of the Eastern Steppe, of the Gobi Desert, of Genghis Khan, of Chinese domination, of Soviet allegiance, of isolation caused by politics as well as by challenging topography and vicious climate, and of a unique cultural festival. Sain baina uu.

Eurasian Steppe, vast plains of grass and shrubs, stretches about 8,000 kilometres from Hungary in the west to Manchuria in the east, though it is divided into distinct segments by various mountain ranges. The section known as the Eastern Steppe extends about 700km north to south, and 2,500km west to east, between the Altai Mountains and the Greater Khingan Range, centred on Mongolia.

Here, the seasonal fluctuations of temperature are more extreme than anywhere else on earth, with summers soaring over 40°C and winters plunging below -40°C. This makes it a harsh land for human habitation, and encourages peripatetic lifestyles.

Today, Mongolia is the most sparsely populated country on the planet, with a population of only three million people, and a density of just two per square kilometre (compared to say Hong Kong with more than 7,000). Nomadic farmers tend their herds in much the same way they have for thousands of years.

The most forbidding part of all, of course, is Gobi, the fifth largest desert in the world, 1,600km long and 500km wide, most of which is scrubby rather than sandy.

The Eastern Steppe was ruled by disparate itinerant tribes from before the time of Christ. These included the Xiongnu (third century BC to first century AD), the Xianbei State (93–234), the Rouran Khaganate (330–555), the First (552–603) and Second Turkic Khaganates (682–744), then the Liao Dynasty (916-1125). The competing tribes in these kingdoms were united only after the arrival in the late twelfth century of Temüjin, eldest child of Yesugei, a Mongol chieftain of the Borjigin clan.

In 1206, Temüjin, meaning blacksmith, formally adopted the honorific title Genghis Khan (here spelled, and pronounced phonetically, as Chinggis Khaan), the precise meaning of which is disputed, though it is usually interpreted to mean “Lord of the Felt-Tent-Dwellers”. He transformed the Mongols’ tribal structure into a meritocratic fighting force that brutally forged an empire ultimately stretching from China through Central Asia across Persia, Mesopotamia and the Levant to Eastern Europe, reaching as far north as the Arctic and down to the Himalayas. Since his death in 1227, Genghis Khan has been a byword in large parts of the world for hideous desecration, though here he has been deified, and modern Mongolians recognise him as the founding father of their nation. His story is warmly told at the Chinggis Khaan Museum in Ulaanbaatar, and he will be present with us throughout our deep dive into Mongolia.

As Genghis Khan’s heirs sent out armies in every direction, within fifty years of his death the Mongol Empire began to fragment over succession disputes about which of his sons and grandsons were the authorised descendants. These conflicts were compounded by ideological disagreements over whether they should adopt a settled and cosmopolitan lifestyle, or continue their nomadic approach.

The Yuan Dynasty, Mongols led by Kublai Khan, a grandson of Genghis Khan, based in Khanbaliq, the forerunner of Beijing, seized eastern parts of this empire in 1271. It was these Yuan emperors who converted to Tibetan Buddhism, thereby bringing the faith to shamanist Mongolia for the first time.

Meanwhile, Marco Polo, the Venetian explorer, arrived in China, also in 1271, and spent the next twenty-four years travelling the Silk Road through Mongolia and China, including a stint as a foreign emissary of Kublai Khan. Polo thus took back to Europe for the first time stories of the Mongol Empire and the Yuan Dynasty, as well as envious examples of their paper money, porcelain and gunpowder.

The Yuans collapsed in 1368, causing their retreat to the Mongolian Plateau, marking the start of the rump state Northern Yuan Dynasty, which staggered on until 1635. In 1691, Mongolia was subsumed into China by the Manchu-led Qing Dynasty. It was during this period that Outer Mongolia, now the country of Mongolia plus the Republic of Tuva in Russia, was identified as a separate territory to Inner Mongolia, land closer to Beijing with a majority Han population that remains in China to this day.

During the Xinhai Revolution of 1911, which toppled the Qing Dynasty and established the Republic of China, the Outer Mongolian government led by Bogd Khan declared independence. However, inspired by the Bolsheviks’ October Revolution in 1917, the Mongolian People’s Party was formed and in 1921 led an uprising of their own, backed by the Red Army. They defeated the White Russian forces, evicted the Chinese rulers, and in 1924 founded the Mongolian People’s Republic as a satellite state of the Soviet Union that was immediately cut off from the rest of the world.

Just like today, back then most educated males were monks or nobles, contributing little to the economy, and the rest were illiterate nomads shepherding livestock that at that time belonged mainly to the monasteries and the aristocrats, though these days at least they tend to be smallholdings. The communist prescription was forcible collectivisation and Stalin-style purges in the late 1930s that murdered the religious, the wealthy, White Russian Buryat minorities, and as much as 10% of the Mongolian population.

Following the collapse of the USSR, the Mongolian Revolution of 1990 led to a new constitution, a multi-party system, a market economy, and a snazzy national flag. Despite all that, in the way of these things, the newly reformed Mongolian People’s Party maintained its rule in the early years of the new era, and despite periods of opposition is back in power again today. Plus ça change, just before we arrived in the country the MPP prime minister was ousted by a rival party official after public anger over his son’s extravagant lifestyle. Meanwhile, little or nothing can prevent Mongolia being squeezed by its two giant neighbours, dependent on Russia for its energy supplies, and in thrall to China for its trade in everything else.

Although Mongolia is renowned as a difficult country to get to, it is a surprisingly easy place to enter. British citizens, for instance, have visa-free access for up to 30 days within any six-month period.

The territory is colossal. There are internal flights to destinations at the extremities, including highly prized Lake Khövsgöl in the northwest, and usually some places can be reached by train because the Trans-Siberian Railway, which runs from Moscow to Beijing, passes through the country. Unfortunately, the northern segment is currently closed because of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, although you can still go south to Beijing.

However, outside the capital and only real city, Ulaanbaatar, there are few roads and few basic tourist facilities, such as hotels and restaurants. This creates two significant challenges for those looking to visit this exotic location independently and in style.

First, in style is difficult. Although there are chichi aspects to Ulaanbaatar, most of rural Mongolia is in subsistence poverty. To experience the Steppe and the Gobi you will often have to sleep and eat in ger camps, like yurts, which are traditionally used for nomadic living, and homestays, usually without running water.

Second, independently is all but impossible. For starters, gers and homestays are hard for foreigners to reserve directly. Moreover, the lack of roads means most of the time you need to travel on tracks not marked on Google Maps, and therefore require a local driver, guide and Toyota Land Cruiser. Hence, a cottage industry of travel agents has sprung up to try to turn independent travellers into package tourists.

![]()

There is no doubt this is frustrating. Most agents simply sent us their standard itineraries and advised us to join a group tour. In the end we went with Travel Buddies because they were the most willing to let us sculpt our own private schedule.

We still managed to sort a hybrid trip. We arranged our own time in Ulaanbaatar, including at the Naadam Festival, and we rented a self-drive Russian Patriot from Sixt because it is easy to visit the Genghis Khan Statue Complex as well as the Gorkhi-Terelj and Hustai National Parks independently as there are paved roads marked on maps. Incidentally, we had to pay a deposit of 6m tögrög (€1 is about MNT3,500) that we did not get back for a month. Despite warnings to the contrary, the standard of driving is more than fine.

For the Steppe, centred on the Orkhon Valley and the ancient capital of the Mongol Empire at Kharkhorin, and the Gobi, as far south as Dalanzadgad, we booked a private tour with a driver and guide. While we did everything we could to escape the yoke of our chaperones, there were inevitable annoyances. They were pleasant enough, of course, but they did not – how could they? – understand that we would have preferred to be left to our own devices and take our own decisions.

With such freezing winters, the best time to come is of course summer. Even though this is technically the rainy season, that really means little more than occasional showers, often at night, every few days. That said, locals report that in recent years the rains have been getting heavier and longer because of climate change.

Ulaanbaatar & Around

Ulaanbaatar

The most frequent flights to the capital, previously called Urguu but since 1924 named Ulaanbaatar, meaning “Red Hero”, come from Beijing and Seoul, though there are also direct connections with Istanbul, Frankfurt and occasionally other places too. From the air as you approach, you can see miles and miles of rolling brown and green hills until UB, as it is universally called locally, hoves into view 1,300m above sea level.

This is the world’s coldest capital city by average yearly temperature, largely thanks to icy winters, though it is also pretty nippy in the evenings even during the summer. That notwithstanding, this is a pleasant city, easy to get to grips with, and I advise you not to pass through too quickly on your way to the wilderness as there is plenty of fun to be found here.

Genghis Khan International Airport is south of the city, in the middle of the Steppe. You can buy a visa on arrival, though most nationalities will not need one. After getting a simple passport stamp, the terminal is a good place to use an ATM and get a cheap Mobicom or Unitel SIM package, which you will need.

From here to UB, you have to take a loop around the Bogd Khan Mountain, going east or west, a journey of 75km, on Asia Highway 3. Although this is one of the very few tarmac roads in the whole country, it took us about two and a half hours thanks to the extraordinary congestion. We did arrive at the busiest time of the year, a few days before the Naadam Festival, but locals report the traffic has been getting worse and worse as more and more rural people move to the big city for education and work. Ulaanbaatar is now home to 1.5m residents, about half those who live in Mongolia. The best way to get about beyond the walkable centre is to simply flag any private car and offer to pay them to take you where you want to go. Failing that, try UBCab.

A good place to start is Zaisan Hill, in the south, which hosts a Soviet memorial and offers panoramic views.

The city was founded in 1639, with the permanent settlement of the Citadel of the Lord of Mongolia’s Buddhist Sangha. There is a monument marking the claimed exact spot, near a statue of Marco Polo, close to Sukhbaatar Square.

Sukhbaatar Square is the centre of today’s city. It is named after a hero of the 1921 Revolution, Damdin Sukhbaatar, who has an equestrian bronze statue in its middle. All around the vast open space are fabulous low-rise Soviet-era buildings, and beyond them are the beginnings of a forest of contemporary skyscrapers.

The most imposing edifice is on the north side: Parliament House, which actually houses both the legislature and the executive. It has a gigantic statue of Genghis Khan at the top of a series of steps up to its formal entrance.

To the west are the long green City Hall and the Greco-Roman columned Stock Exchange.

On the east are the candy-striped State Opera and Ballet Theatre, and the colourful pillared Cultural Palace.

After the Berlin Wall fell, demonstrators rallied in countries across the Soviet Union and its satellite states, including Mongolia. On 9 March 1990, outside the minor Yalalt picture house, now the Tengis cinema, and the State Central Museum, now the Natural History Museum, 100,000 protestors bravely assembled to demand the overthrow of the communist regime.

They marched 1.2km east towards Parliament House, which then hosted the People’s Great Hural, the Council of Ministers, and the MPP HQ. Though their starting point is still ramshackle, it has a vital place in Mongolian history, and it has subsequently been renamed Liberty Square. One of the leaders of the democracy movement, Sanjaasürengiin Zorig, was later murdered in unresolved circumstances. He is still revered as the man who ushered in freedom, and is recognised near Sukhbaatar Square with both a formal life-size statue and a more appropriately revolutionary huge mural on the end of a housing estate.

It was not until the collapse of communism that openly practicing Buddhism became possible once again. Two centuries previously, there had been more than a hundred sum (temples) and khiid (monasteries) in Urguu, though only a handful survived the atrocities of the 1930s. These purges were led by General Khorloogiin Choibalsan, whose statue still stands outside the National University just north of Parliament House.

The principal Buddhist complex, the spiritual centre of Ulaanbaatar, is Gandantegchinlen Monastery, roughly meaning “Great Place of Complete Joy”. This Tibetan-style shrine was founded in 1809 in the north-west of the city. In 1939, Choibalsan ordered its destruction, though it was only partially damaged. In 1944, however, Stalin pressured Choibalsan into restoring it as a showpiece for the visit of US Vice-President Henry Wallace to demonstrate to his Western allies that the communist regime permitted freedom of religion. From then until 1989 it was the only active monastery in the country.

They are relaxed in these parts these days, so you can visit in shorts and keep on your shoes. The centrepiece of Gandantegchinlen is Janraisig Temple, constructed in the 1910s, which holds a 26m-tall standing statue of Migjid Janraisig Süm, the Buddha of Compassion, surrounded by hundreds of small statues of Ayush, the Buddha of Longevity. Sadly this Janraisig is a replacement, put there in 1996 after independence, as the original was removed by the Soviets in 1937 to be melted to down to make bullets.

To the right, in a small courtyard, are two smaller colourful temples, Didan-Lavran and Ochidara, where in the early mornings lamas in their blood-red robes sit on rows of benches chanting their mantras, which makes a lovely spiritual atmosphere. Visitors are permitted to wander around them quite freely, though photos are understandably outlawed.

To the left is a large new temple, Kiidiin Zahirgaa, behind which is the monastery itself where today’s monks live and learn.

The other main Buddhist complex in UB is Choijin Lama, home to five small temples with classic intricately-carved hip-and-gable rooves. It was opened in 1908, just south of Sukhbaatar Square, where it is overlooked by the emerging skyscrapers of the city centre.

Most Mongolians are said to adhere to a blend of Buddhism and Shamanism. Shamans claim to be able to direct spiritual energy into the corporeal world through trance. Their headquarters, the Centre of Shaman Eternal Heavenly Sophistication, is next door to one of the city’s many karaoke bars. It is open 9am to 3pm, and has authentic ceremonies once a week.

During the crucial interregnum years of 1911 to 1924, the ruler of Mongolia was Bogd Khan. His Winter Palace, a two-story Russian-style house built between 1893 and 1905, is on the standard tour guide itineraries.

I imagine almost every agent also sends their tours to the traditional show at the National Theatre. When we went, it was packed, mostly with Chinese tourists, although all the PA announcements and commentary are in English. Starting at 6pm every night, this is the classic showcase that introduces traditional Mongolian culture and heritage, which has been reborn and repackaged since independence. The Tumen Ekh Ensemble performs twenty or so short snippets over an hour of acrobatic contortion, folk music, shaman dancing, mask dancing, and iconic throat singing.

Later that evening, we went across the street to Fat Cat Jazz Club with some of the coolest kidz in Asia, who are also big into hip hop and folk metal.

Around here are several beer gardens, including UB Street Food, Café 78, MB and Grand Khan, which although it calls itself an Irish Pub is in fact a long way from those you normally come across around the world. They all sell rib-eye steaks and a range of amber lagers and craft beers. The most popular include a brand called Chinggis. Incidentally, do not come here on the first day of any month, as UB will be totally dry.

The national drink is of course vodka. There are scores of brands, the most popular include Genghis, inevitably, as well as Soyombo and Xapaa, though we never took to Shiguderi, made from fermented cow’s milk. When you receive a glass of vodka, apparently it is customary to dip your right-hand ring-finger into it and flick a drop towards the sky. Tölöö.

Mongolia is no foodies’ paradise. Surprisingly, to me at least, Mongolian BBQ has nothing to do with Mongolia, nor even barbeques. The concept was in fact invented by Chinese immigrants to Taiwan in the 1950s and involves meat cooked on a flatiron grill like teppanyaki.

The Modern Nomads chain is popular, where you can order an appetiser called “Calories” (roasted beef marrow with cheese, plus fried scone and liver paste with sour cream), and a “Socialism Salad” (beef tongue with cucumber and cabbage). More typically, main courses include buuz fried or steamed dumplings, with goat, beef, horse, camel or marmot, and khuushuur meat pastries a bit like Argentinian empanadas. It is usual to accept food and drink with your right hand; you use your left hand solely support your right elbow if the food is heavy. And Mongolian meals are heavy, in that they are high in fat and low on salad and vegetables.

You will usually not only need to book a table in advance, you will also have to order your meal a day or two ahead too, so the kitchen has enough chance to buy the raw ingredients to make your meal. They tend to close around 9pm.

This may be a legacy of Ulaanbaatar’s time as the capital of a USSR satellite state. This period was overlooked by all the agencies we spoke to while arranging our programme, though it is worth flagging that Koryo Tours has a specialist package dedicated to examining the remnants of Communist Mongolia. However, we explored alone the numerous examples of Soviet-era architecture in the city.

The Russian district is to the east, where 1960s tower blocks, crumbling pavements and unpaved roads remain much as they were in 1990. A good place to start to reflect on that time is the Military Museum, which has Soviet T-72 tanks and MiG-29 fighter planes in its overgrown courtyard.

Nearby is the house used by Marshall Georgy Zukhov when he was stationed here from 1938 to 1940. One of Stalin’s most senior generals and later his Minister of Defence, Zukhov was sent here to prevent the expansion of the Japanese Imperial Army from Manchuria into spheres of Soviet influence. There is an imposing bust of him in the street outside.

It has become a tenet of popular culture that teenagers behind the Iron Curtain were listening to smuggled records by Western pop acts, especially the Beatles. To honour them here in UB, Beatles Square has a memorial of not completely accurate representations of John, Paul, George and Ringo against a large red apple, their label.

At the end of Beatles Square is the State Department Store, dating from 1921. This is the place the tour guides advise you to buy your souvenirs, and there are a lot of them on the sixth floor. There is also an enormous selection of local vodkas on the first floor to take home.

The best place to shop, however, is the Narantuul Black Market, a warren of outdoor alleyways selling leather belts and shoes, jewellery, and homeware. Aimed mostly at locals, it is a joy to wander around, and it is also the best place to pick up a vintage snuff bottle, gorgeous onyx versions of the little flasks used by every nomadic herder. The most exquisite cost more than our guide’s monthly salary.

The other must-have is a cashmere woollen. Gobi sells cashmere from goats, premium quality scarves, sweaters and jackets with a wide choice of designs and colours at prices about which Westerners can only dream. Bodio offers slightly thicker and coarser down from yaks.

The premier hotel in the country is the Shangri-La, at the centre of its own high-end bubble that includes the mall, the fitness centre and several excellent restaurants and swish bars. The iconic and storied option is the Ulaanbaatar Hotel. Opened in 1961, the first lodgings in the country, the first public building with running warm water, designed by the wife of then Communist local leader, Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal, it has recently been renovated. However, I would advise against staying here as the service is too awful.

Naadam Festival

Without a shadow of a doubt, the best time to come to Mongolia is mid-July for the Naadam Festival, the country’s preeminent celebration. The main event takes place in the National Stadium, over three days, 11th to 13th, with smaller activities all around the country. It is known as eriin gurvan naadam, “the three games of men”: wrestling, archery and horse racing (though these days women also participate in the horse racing and the archery if not the wrestling).

Tickets for the National Stadium go on sale just a few weeks before it starts, in three categories: tourist seats (under a roof), regular seats (with no roof), and standing areas. With massive demand for the Opening Ceremony, and a total capacity of only 12,500, foreigners are best to place a reservation via an agent weeks if not months in advance, though you absolutely do not need to be accompanied by a guide on the day.

The action begins on the 11th at 9.30am in Sukhbaatar Square, where crowds gather to watch Genghis Khan’s “nine horse’s tails”, representing the nine main tribes of the Mongol Empire, start a ceremonial procession to the National Stadium. They are paraded down the steps past the Genghis Khan statue, and handed to officers on horseback who set off in regimented order followed by a cavalcade of spectators, including us. By the way, it is also worth coming to Sukhbaatar Square the day before to watch the full dress rehearsal by the uniformed marchers and the military band.

The procession finally erupts in chaos and uproar at the National Stadium, 3km south, where all the action takes place under the watchful eye of a gigantic version of the most common portrait of Genghis Khan, drawn in 1278. The two-hour Opening Ceremony begins at 11am. Following a live speech from the President, which since 2021 has been Ukhnaagiin Khürelsükh, there is a spectacular presentation of Mongolia’s history and cultural heritage involving 2,500 dancers and horse-riders.

The games begin at 1pm. It is worth getting a schedule of the events, although you should expect everything to run significantly late; you can pick one up from any tourist information gazebo. The wrestling takes place in the stadium, the archery in a little arena of its own nearby, and the horse racing at Khui Doloon Khudag, 40km west of UB. Whatever your guide says, it is not possible to see the Opening Ceremony and all three sports in one day.

Aggressively camp in their red or blue loincloths, 1,024 wrestlers participate in knock-out rounds over the three days. They pour onto the field hundreds at a time as bouts of no more than 60 seconds break out seemingly randomly all over the place in a whirl of frenetic activity.

In the archery, lines of around twenty men – or women – shoot arrows 50m towards a small pile of coloured cubes. Each has an assistant dangerously positioned near their target to advise by open arms how far away their arrows fall. Again, there are repeat knock-outs but proceedings are subject to delay as various senior politicians arrive to work the crowd.

Horses are central to Mongolian culture, so the equine events have a major status all of their own. It is quite easy to drive yourself to Khui Doloon Khudag, a dusty bowl among the gently rolling hills, and the “finish of horse race” is even marked on Google Maps. There are horses and gers as far as the eye can see in all directions, locals everywhere are selling anything you want from the back of their cars, and there is a general commotion from the fairground attractions and of course rides for spectators on ponies and camels. We saw two kinds of racing.

As many as twenty horses at a time run very long distances, up to 30km depending on their age. They are ridden by child jockeys, aged 6 to 11, who have to weigh under 35kg, dressed in colourful overalls, without saddle or stirrups, though they whip their mounts constantly with short pieces of rope. They start from beyond the horizon, though everyone watches live on Facebook and hears the excitable commentary – in Mongolian, of course – blare out over the scratchy PA system. They run in a straight line and gradually the lights of the accompanying vehicles and the dust kicked up by the hooves comes into view, thundering towards us like the Lakota Sioux in Dances With Wolves. Rather than a fort, we are in the little grandstand at the finish line.

Near us, there is an oval track scratched into the earth with another couple of small grandstands at the start/finish line. Here there are short 1 -2km races for horses that have to move with a sort of trotting shuffle. These have adult jockeys in traditional costume.

It is a privilege to be at this wonderful experience. Naadam is much more than a sports event. It is a cultural celebration, a national carnival with local street parties, full of food stalls, pop-up gazebos, musical acts, and knucklebone shooting (check it out).

Above all, Naadam showcases the skills that helped Genghis Khan win so many wars and build such an empire. I knew before I came that he was a Mongolian hero, and I assumed he would be honoured in the way that many national founders are, with a few statues and the title of the international airport. But Mongolia has really doubled-down. Since the release of the Soviet embrace, his story has been mythologised and entrenched, telling a foundational narrative of the country, and so rebuilding a sense of unifying national identity. His face is on the bank notes, in every public building and in many private homes too. His name is lent to everything from streets to pubs. Considered the definition of brutality and destruction across China, Central Asia, Russia, the Middle East and Eastern Europe, here he is the ubiquitous and loved warrior. Naadam is the contemporary expression of his power that reveals today’s country is still in thrall to his thirteenth century triumphs.

Genghis Khan Statue Complex

As if further proof were needed of the hold that Genghis Khan still has on Mongolia, an astonishing tribute to him was unveiled in 2008. The biggest single attraction in the country – in every sense – is the Genghis Khan Statue Complex at Tsonjun Boldog, 50km east of Ulaanbaatar, an easy drive on smooth tarmac in your own car.

At 40m tall, this is the largest equine statue in the world, and it takes a while to adjust to its presence here in the middle of the Steppe. There is an excellent gift shop in the base, from where you can climb up inside to reach the horse’s mane for close-ups of the great man’s head and wide-angles of the surrounding green plains.

Genghis Khan & the Mongol Empire

From a Mongolian perspective, it can feel like abroad that their national champion, Chinggis Khaan, has been rather misunderstood by history and caricatured in popular culture. For instance, Hollywood trivialised him in The Conqueror, starring of all people John Wayne. More recently, there was a frivolously ignorant and condescending two-part biography on The Rest is History (His Rise and as Lord), which managed not to take him at all seriously.

Yet he is obviously a hugely significant historical figure, the man who forged the largest contiguous empire the world has ever known. Born as Temüjin in 1162, he evidently owned extraordinarily sophisticated political and leadership talents, able to shape a loyal following based on merit not kinship. He melded an army of 200,000 men from eighty feuding clans in his quest for world domination, for which he believed the shamanic supreme deity Tengri had destined him.

Using some of the fighting skills on display at Naadam, with composite-bows fired from horseback, he imposed laws, taxes and a new script on the jumble of tribes that comprised his rapidly assembled confederate empire. Ultimately, his dominion stretched from China to Eastern Europe, facilitating unprecedented commercial and cultural exchange over the Pax Mongolica.

There is no doubt of his brutality. I have seen first-hand the consequences of his policy of demanding surrender or inflicting destruction, notably the flattening of Bukhara and Samarkand in Uzbekistan, and Konye Urgench and Merv in Turkmenistan. There are reliable estimates he murdered as many as 4 million people, though oddly no archaeological evidence of mass graves has yet been uncovered.

The oldest surviving work in Mongolian, The Secret History of the Mongols, is a biography that was published soon after his death at the age of 65 in 1227. Through sketchy sources and apocryphal storytelling, it has added lustre to the mixed mythology.

To understand Mongolia today, it is bizarrely essential to put time and effort into understanding a thirteenth century warlord who is one of the most famous and controversial figures in history.

Gorkhi-Terelj National Park

Just 60km east of Ulaanbaatar, beyond the Genghis Khan Statue Complex, Gorkhi-Terelj National Park is also easy to reach on your own, though it is mostly frequented by coach parties of older people making short trips to the country. It is renowned for its dramatic rock formations, horseback riding, hiking and camping, and its grasslands are speckled with little round white ger camps.

The main site is the Aryapala Meditation Temple, reached by a 15km drive from the park gate to the end of the valley, followed by a short walk up 108 white steps, which apparently and discouragingly illustrate the meaninglessness of human life. There are 108 praying wheels around the top, and Om Mani Padme Hum, a Buddhist mantra, is crafted onto the rocks beyond in gigantic lettering, which you are encouraged to recite in the temple 108 times. This is a number that Buddhists like.

The inside of the temple is brightly colourful, but honestly the principal reason for coming here is the view back. At the other end of the valley, you can just make out Turtle Rock, an interesting formation that from a certain angle does indeed look like an enormous terrapin.

Hustai National Park

On the other side of Ulaanbaatar, just 100km west, Hustai is also easy to explore independently because the road to get there is paved, and though the single path through the National Park is not, it is not especially bumpy or hilly. However, it is usual to stop here on a tour to or from the Orkhon Valley and Kharkhorin.

The time to be here is just after sunrise or just before sunset. That is when its rare Przewalski wild and untameable white horses come down from the hilltops to drink from the water on the valley floor. There are only four hundred of them and this is a vast area, so during the heat of the day you will be lucky to see them even through binoculars.

Western Mongolia is also the home of Golden Eagles, which have been central to the Mongolian hunting tradition since the time of Genghis Khan. Skilled bürkütshi train these beautiful birds, which can weigh up to 7kg and have a wing span of more than 2m, to catch hares and foxes.

It is possible to spot these giants circling around the grasslands, though sadly it is more common to see them tied to posts for photos at tourist sites.

Orkhon Valley & Kharkhorin in the Steppe

The Mongolian Steppe is vast, covering an area of almost a million square kilometres, yet is has almost no asphalt roads. To stand any chance of getting to grips with any of it, it is advisable to focus on a relatively accessible but representative segment, such as the Orkhon Valley to the west of Ulaanbaatar. Orkhon is the most alluring place we visited in Mongolia, and it has the additional advantage of close proximity to the ancient capital of the Mongol Empire at Kharkhorin.

Hotels are few and far between in the Steppe, so you will undoubtedly stay in ger camps. Gers are the traditional accommodation of nomadic herders, circular white wood-and-felt homes with pointed rooves. In the Steppe they are pretty basic, though in the Gobi for tourists the best are sturdy constructions on solid foundations, with double-beds, ensuite bathrooms, stoves for heating and fans for cooling, at camps with restaurants, bars and Wi-Fi. They tend to be bigger, cleaner and warmer than their cousins, Central Asian yurts. They say it is customary for women to enter a ger on the left and men on the right, though as they all have narrow doors in reality that is quite hard to arrange.

The other option is a homestay with one of the 200,000 nomadic families who live on the Steppe. I cannot recommend this strongly enough. Despite, or maybe because of, the lack of running water and other basics, this was a highlight of our expedition in Mongolia. This was the first time this family had hosted foreign guests, and it was clear they enjoyed it as much as we did, not only because we left a spree of useful gifts such as batteries and pens. Their closest neighbours, from miles up the valley, were constantly popping in for a look at the strange visitors.

They told us they have government certificates guaranteeing that this land is theirs. So when they move the five little gers that make up their family home 10km into the mountains for greater shelter every winter, they are secure that their plot on the valley floor will still be there for them when they return each summer.

At one level, they live a simple life unchanged in centuries, where the toilet is a hole-in-the-ground hidden on three sides by a wooden fence but without a door. Their home is swarmed by goats and yaks, which are astonishingly friendly, coming up to lick our hands. Yaks, hairy oxen, can be ridden like horses, in races and for polo. At 7am, we joined in the daily routine of milking them. Half of this milk is then churned into a delicious butter, which is apparently popular for making sculptures too.

We helped out with the preparation of the meals (minced beef and onion steamed dumplings for dinner, and urum, clotted cream from yak’s milk, with aaruul, dried curd, for breakfast). All evening we shared sniffs from a bottle of snuff (tobacco soaked in water), and passed around a repeatedly replenished little bowl of airag (home-made vodka usually from fermented horse’s milk but in our case fermented yak’s milk) and the single shot-glass of Soyombo vodka we brought as a present.

In other ways, the ownership of cars, motorbikes, solar power, and smart phones with 4G connections are changing everything. Our new friends told us that no foreigners came to the valley until about fifteen years ago so their knowledge of the outside world was scant; but while we were here their ten year-old spent the entire time watching YouTube on his phone. He still has to move 20km to stay with his grandmother during term time though, so he can access the nearest village and get to the closest school.

Orkhon Valley

The open fields, stretching to the horizon without enclosures, lend the Steppe a Medieval feel, buzzing with livestock around the smattering of families’ gers and occasional larger tourist camps of no more than ten or twenty tents. Horses and cattle as well as goats and yaks are everywhere, and nowhere more so than here in the Orkhon Valley.

Although you could come here on the way to or from the Gobi Desert, if you did arrive straight from Ulaanbaatar it is 350km southwest of the capital, a drive that would take as much as ten hours over the bumpy, often muddy, tracks. We are conscious that while it is never as much fun as driving ourselves, and making our own decisions, there is no way we could do this on our own. The internet is intermittent, Google Maps does not show most of these faint paths anyway, and even our driver was occasionally caught out getting lost.

The valley itself, 15km wide, spreading out from both banks of the eponymous river, and 80km long, is breathtakingly beautiful. Its waterfall is a particular attraction, reached by a short horse ride, for its sunset prettiness as well as the makeshift zipwire that flies across in front of it.

In addition to its natural charms, the Orkhon Valley is a UNESCO World Heritage Site because of its role as the cradle of nomadic civilisation. Its earliest monuments are Deer Stones, carved tablets assumed to be at the head of graves, which date from the Bronze Age, 5,000 years ago.

It is not far north across the valley from the main set of Deer Stones to the Tovkhon Khiid Monastery, though because of the squiggles in the tracks it is a journey that takes a couple of hours when the rains have made them boggy.

Tovkhon, “Land of Happy Solitude”, was first built in 1653 by Zanabazar, the original Buddhist leader in Mongolia, though it was largely destroyed in 1688 by the Oirat Mongols from the Altai region of Siberia. It was restored in 1773 but desecrated again in the 1930s by the Communists. The current edifice was spatchcocked onto the remains of the original two buildings after the arrival of democracy, in 1997.

It is on Shireet Ulaan Uul Mountain, 2,600m above sea-level and beyond a picturesque fir-tree forest on the lower slopes. It is an easy 3km journey up by foot or on horse. Half-a-dozen lamas live here, and we happily wandered around while they incanted their mantras. Just up from the main temple is a little rock-climb, which leads to a cracking perspective of the Khangai range.

Kharkhorin

The Orkhon River flows all the way 100km northeast to Kharkhorin, a drive of roughly ninety minutes, from where it is in turn 360km in the same direction on to Ulaanbaatar, about six hours away.

Kharkhorin, previously called Karakorum, was founded in 1220 by Genghis Khan. It was then anointed capital of the Mongol Empire in 1235 by Ögedei Khan, his third son and the second khan. After the short tenure of Güyük Khan, it flourished between 1251 and 1259 during the reign of Möngke Khan. When Kublai Khan succeeded the throne in 1260, he moved his capital to Khanbaliq, later renamed Beijing, as he defeated the Song Dynasty and became ruler of all China until his death in 1294, by which time he had left behind the Mongol Empire and founded the Yuan Dynasty.

Today, there is little left of this imperial stronghold. The museum contains a model of that ancient capital along with fragments of porcelain and carvings that have been excavated in the town, but that is about it.

As there is nothing here but the ghostly memory of those glory days, the main reason for coming is to experience the wonderful Erdene Zuu Monastery, built to the northeast of the ruins of Karakorum. This was the first in Mongolia, erected in 1586 by Prince Abtai Sain Khan, who elevated Buddhism to the religion of the state. Incidentally, on a hill overlooking the monastery is a stone-carved phallus that is said to restrain the sexual impulses of the monks and so ensure their good behaviour; visitors seeking fertility are encouraged to pray while sitting on this so-called Penis Stone.

Like the Gandantegchinlen Monastery in Ulaanbaatar, Erdene Zuu was damaged under the direction of Khorloogiin Choibalsan in 1939 but then reprieved by Stalin in 1944 as he was seeking to cement relations with the United States at the end of the Second World War by demonstrating religious tolerance.

The site is surrounded by a wall, almost 2km long, in the shape of a Buddhist rosary, and holding 108 (yes, that number again) equally spaced stupas. It was restored as an active shrine in 1990, and these days you are likely to come across the lamas saying their mantras in the Lavrin Temple.

Finally, I should flag that Kharkhorin is an actual proper town, with a fun black market and a four-star hotel, the Ikh Khorum, which has a good gym and an excellent restaurant.

The Gobi Desert

One of the principal attractions of Mongolia is to experience first-hand the beauty and the extremes of the Gobi Desert. During our summer here, we felt temperatures rise to 35°C, though at night it sometimes slumped to a chilly 15°C.

There are several places of topographical and geological marvel, and there are miserable remnants of various monasteries desecrated by the Soviets, including Baga Gazriin Chuluu and Ongi. These points of interest are spread over a wide area, so it takes about a week to get round them all. Luckily, each site has a smattering of ger camps to hand, though they are of variable quality so be sure to press for the best.

After a couple of hours of driving south out of Ulaanbaatar beyond the airport, the hills start to fall away as the grass becomes more patchy. Surprisingly, it is still largely green, and apparently getting more so as climate change brings additional annual rain; in fact, it was pouring as we entered the desert.

This is noticeably sparser of humans and animals than the Steppe. There are fewer villages, fewer cars and just less life. There is little but the occasional ger – not even a tree, not even much trash – with the stars clear in the night sky, creating a tranquillity with the cleanest possible air.

There are, however, goats galore. Their white and brown coats are ideal for cashmere, though the black ones are thought too coarse. These days, they are herded by nomads skidding around on motorbikes not horses.

The Gobi is rich in mineral resources, and we see occasional little coal, copper and gold mines, as well as what appear to be abandoned wooden shacks, which become the herders’ homes during the freezing winter months. Lammergeier, bearded vultures, stand like sentries monitoring our arrival.

After four or five hours, the land gradually becomes more sandy and rocky, and Bactrian two-hump hairy camels become common. Mongolia has half the world’s population; most of the rest are in Inner Mongolia and parts of Central Asia. Some wander free, and some are tied near gers, protected from intruders, like humans taking photos, by ferocious guard dogs.

It is more than 500km south of Ulaanbaatar to the first properly interesting feature, a route of almost ten hours. You can break the journey at any of several ger camps on the way. By now we are in Middle Gobi, and suddenly rising from the barren plain is Tsagaan Suvarga, the White Stupa, a limestone canyon of 30m-high cliff walls. The best view of it is at sunrise.

The best view from it is at sunset. Not all our overnights are at ger camps and here the Gobi Caravanserai is a minimalist eco-lodge with an excellent terrace restaurant, right on the sand in the middle of the desert.

From here it is about 180km, which takes roughly two-and-a-half hours, down to Dalanzadgad in South Gobi. Mongolia’s second city is 1,470m above sea level, but only in the foothills of the Altai Mountains. There is an impressive gate on the approach.

There is not much here, but you need to pass through the city to reach the Gurvan Saikhan National Park, a rectangle running 380km east-west and 80km north-south, with Dalanzadgad at its east edge.

The National Park covers the eastern portion of the Altai Mountains, which reach up to 2,600m and are spread across a vast area where Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan and Russia converge, stretching from the Gobi to Siberia. Apart from its natural beauty, rising out of the desert plain, where for much of the year the mountain tops are snow-capped and waterfalls are held in motion as the flow turned to ice, this is a crucial ecological habitat for great-horned argali sheep, ibex, lynx, bears and snow leopards.

Sadly, there are stuffed and skinned versions of these endangered creatures in the museum at the entrance to Yolyn Am, known as Vulture Valley. An hour west of Dalanzadgad, Yolyn Am is the central feature for visitors in the eastern section of the National Park. Up in the Altai, this is a long canyon of tall grass with a weak stream running through it. There is a pleasant 10km drive before the passage narrows sufficiently that you need to ramble on foot or mount a horse the rest of the way, another 3km or so. As the channel narrows further still, you wander over cute bridges and scramble down little waterfalls until a sign warns you to go no further. It takes no more than a couple of hours round trip, and it is best to come when there is a high sun to avoid too much being hidden in shade.

From here we drive west along the foothills of the Altai for two hours before turning back into the mountains at the coffee shop that some enterprising soul has set up in the middle of the desert, miles from anywhere.

After a total of 180km – four hours of bouncing across the desert – we come through a pass in the mountains at the centre of the National Park. This haw-haw frames a stunning view of another great plain below, the rocky mountains on the other side of it, and between them a 100km-long 20km-wide line of brown sand dunes.

This is Khongoryn Els, the Singing Dunes, so called apparently because of the noise they are reputed to make when you walk on them after rain. Just in front of them are several small herders’ gers, where you can cadge a ride on a two-hump camel.

The real treat is to climb the 250m-high Duut Mankhan sand dune, along with a parade of young kids carrying boards for zipping down again. It is a steep and stiff trudge sinking into the sand for more than half an hour, but the sunset panoramas of the valley below and the virgin dunes at the top are well worth the struggle.

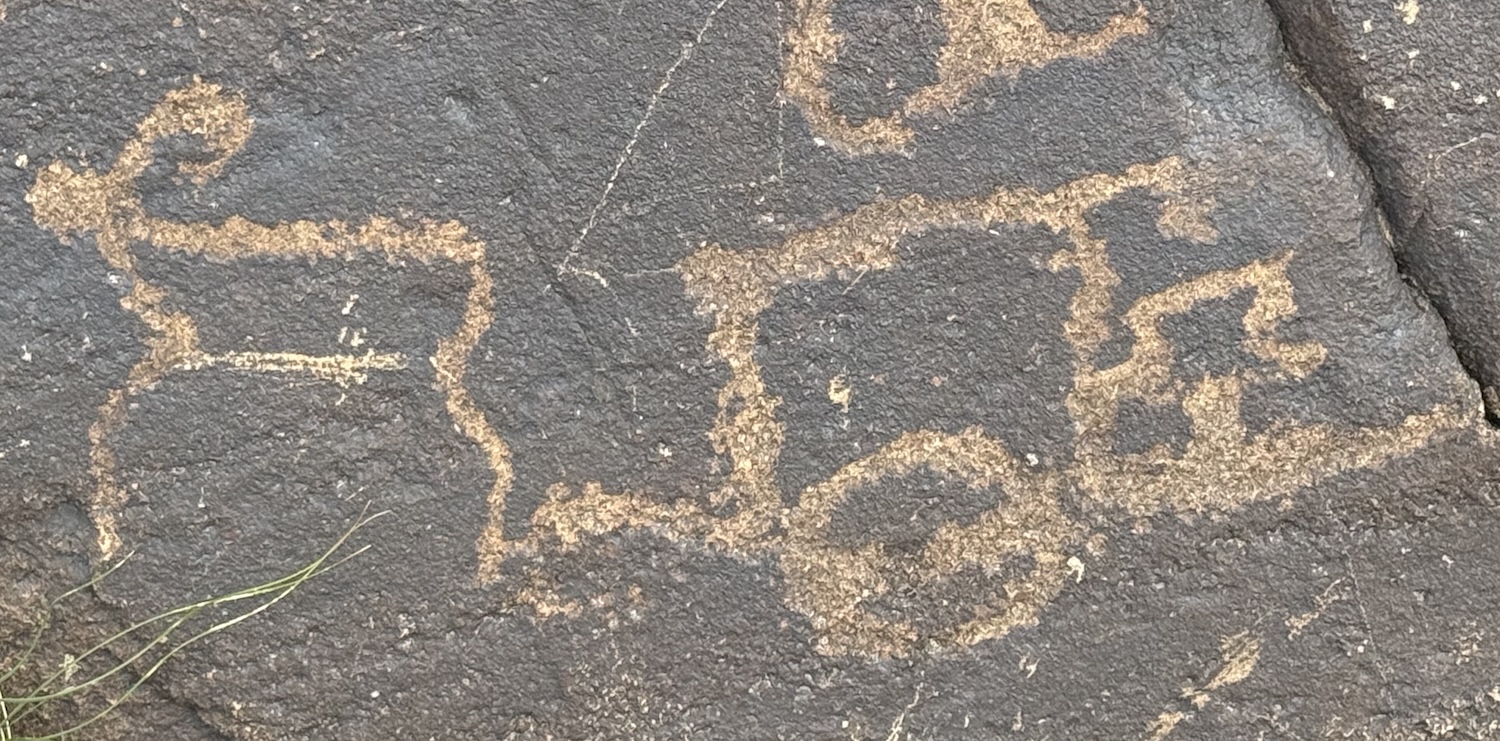

Khongoryn Els is the furthest south and west we go in the Gobi as we now circle back east-north-east for 130km, another three bumpy hours, to reach Khavtsgait on the north edge of the National Park. There are several rocky locations across the desert where travellers have scratched the outline shapes of humans and animals dating back more than 9,000 years, and the best of these petroglyphs are here at Khavtsgait. There are hundreds of drawings, including a cart pulled by a horned creature, at the top of a steep fifteen minute clamber up a hill.

Not far from here is Three Camel Lodge, considered the most luxurious accommodation in the Gobi Desert. However, they require you to stay more than one night and also book tours with them, and they do not permit guides and drivers to stay, which are significant drawbacks.

It is another 40km, just an hour, north across the plain to reach Bayanzag Canyon, known as the Flaming Cliffs because of the fiery colour of the sandstone that formed them 60-70m years ago in the Cretaceous Period.

This is regarded as the most popular site in the Gobi because, in addition to their aesthetic splendour, this is where humans first discovered dinosaur eggs. There is a terrific short film in the museum at the entrance about the team led by American explorer Roy Chapman Andrews that unearthed this site in the 1920s. Using primitive footage shot at the time, the movie reveals that the eggs were found right next to a fossilised complete skeleton of an adult male dinosaur, which subsequent DNA evidence proves to be the father, who is assumed to have been sheltering them in a cave away from a sandstorm.

Not that far from here, in an area known as Tsoorhai, is a monument marking the spot where Genghis Khan last camped in Mongolia. Having embarked on what turned out to be his final campaign, another invasion of northern China, he fell in 1227. No body or tomb has ever been found, though there is a mausoleum dedicated to him in absentia in Ordos in Inner Mongolia.

As we leave the great warlord behind, this also feels like the perfect place to end our Mongolian adventure by heading back to Ulaanbaatar. Bi Mongold khairtai. Bayarlalaa and bayartai.

10/08/2025 @ 14:36

Absorbing account.

Beautiful photos.

More would certainly enhance the illuminating travelogue.