Oil wealth, liberal Islam and above all a Grand Prix probably captures what many people think of the tiny country of Bahrain if they ever bother to think of it at all. However, beyond those there is also a relaxed capital city with beach resorts, souq shopping, eating and even drinking, as well as heritage sites from both an ancient civilisation and the era of the most successful pearling industry in the region. Then there are some unique oddities including a 400-year-old tree growing in the middle of the desert with no apparent water supply, and a Boeing 747 resting in 20 metres of diveable ocean. It is easy to spend a long weekend here, which I have done half-a-dozen times in the years I have been living and working nearby.

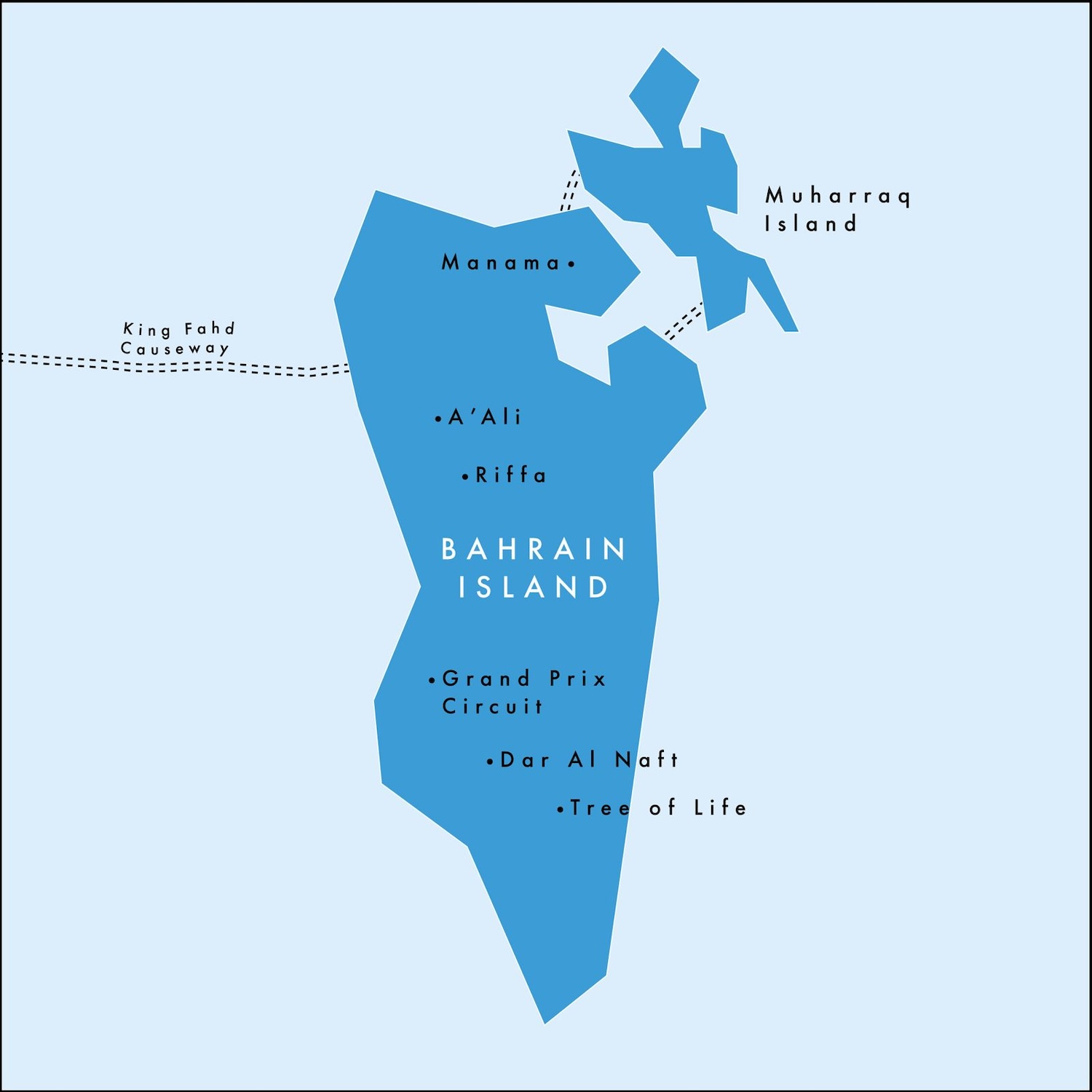

Bahrain is sheltered in a huge inlet in the Arabian Gulf, nestling between Dammam in Saudi Arabia to the west and the Qatar peninsula to the east. A collection of fifty natural islands, the territory has been enlarged with the addition of thirty-three artificial ones. More than 80% of the land mass is on Bahrain Island, which is itself only 50kmx20km.

Bahrain was the capital of the Dilmun civilisation, which dates from roughly 4000 BC but whose heyday as prosperous traders lasted for more than a millennia from about 2000 BC until they were conquered by the Assyrians. After converting to Islam during the lifetime of the Prophet Mohammed (PBUH) in the seventh century, Bahrainis have largely been under Arab rule ever since, apart from a spell in the sixteenth century when they fell to the Portuguese Empire and in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries when they lived under a British Protectorate.

In 1971, like Qatar, Bahrain was set to join the United Arab Emirates at its foundation, but at the eleventh hour declared independence instead. The House of Khalifa has been the local ruling family since 1783, when Ahmed al Fateh became the first hakim or governor; today the Kingdom of Bahrain is a constitutional monarchy that hosts the US Fifth Fleet, which patrols the Arabian Gulf.

Although 75% of Bahrainis are Shia Muslims, the Khalifas are Sunni. They have been accused of human rights abuses while suppressing opposition, notably during the Arab Spring of 2011, and they are reliable allies of Saudi Arabia, for instance joining the boycott of neighbouring Qatar from 2017 to 2021.

Bahrain was the first economy in the Arabian Peninsula to strike oil and the first to diversify, investing heavily in banking and tourism. Of the 1.5 million people who live here, only half are Bahrainis; the rest are low skilled immigrants and high paid expats who have been invited in to support the modernisation of the country. There are in fact very few actual tourists not from adjacent countries so it still feels like a bit of an adventure, but with five star facilities.

Bahrain is one of the most socially liberal of the six Gulf Cooperation Council countries, attracting hordes of Saudis for relaxed weekends of fun forbidden them back home. Alcohol and sheeshas are readily available in bars and restaurants, more so than anywhere else in the GCC, and while you do see plenty of women in head-covering black abayas, even face-covering burqas, and a few men in long white thobes, most are casually dressed in the latest international fashions. Homosexuality is legal and the age of consent is equal, although at 21 it is the oldest in the world.

Bahrainis have a wonky working week, Sunday to Thursday, and a phenomena created by and for expats is the Friday brunch, which actually starts around noon and goes on drunkenly all afternoon in all the major hotels.

It can be a chilly 15°C in the winter but a sizzling 50°C in the summer, when sand storms are also frequent, so the best times to come are the short spring and autumn months. The most buzz is of course around the Grand Prix in March every year.

The oldest international airport in the Arabian Gulf, which has recently undergone a US$1 billion expansion, is on Muharraq Island, to the north of the archipelago, just a fifteen minute cab ride over one of the three bridges that cross the turquoise ocean south to downtown Manama on the north-east corner of Bahrain Island.

Manama

The centre of the old town is at Bab Al Bahrain, the large white gate erected in 1949 opposite the historic Post Office building that once housed the government’s administrative offices. Atop it is of course a national flag, the striking red and white jagged tooth you see all over, almost identical to the Qatar flag but a bloodier red. Originally overlooking the sea, this imposing landmark is now landlocked by reclamation and has become the epicentre for taxis because it marks the entrance to the sprawling souq.

The souq swarms around a large complex of cobbled streets full of shops selling all the usual stuff from perfumes, spices and textiles to fruit and veg and knock-off Rolexes. It is open from 9-12.30 in the morning and then again 4-8 in the evening.

This whole area is known as Little India – hosting a community of 300,000 South Asians – and at its core is the wonderful 200-year-old Shrinathji Krishna Temple. That is open only for the three daily prayer times (6.10am, 11.15am and 6.45pm), when anyone can attend. You will almost certainly be the only outsider and by the time you have taken your shoes off in the courtyard opposite the multicoloured entrance to the inner sanctum, you are sure to be welcomed by the temple manager eager to show you around and talk you through its history.

To the east of Bab Al Bahrain is the Yateem Mosque, distinctive because of its unusual feature of a clock tower on its minaret. To the west is the Merchant House boutique hotel, the best in the city, with its charming Indigo rooftop little terrace bar and restaurant of comfy chairs with floral patterns. Around here are two excellent Bahraini restaurants: Naseef is one of a small chain ideal for breakfast trays, machboos dinners, or mango ice creams; and Haji’s Café has been an essential spot since 1950 for traditional local cuisine, where the specialties are tikkas, kebabs and grills.

Facing all this, from the other side of the King Faisal Highway, are the distinctive green glass buildings of the Harbour Towers, not far from the World Trade Centre that looks like a giant pair of tweezers. Those modern skyscrapers are a world away from the buzz of life still happening on these old streets.

The tourist hotels are mostly spread along the north coast of Manama. At the east end of it is an area being developed as Bahrain Bay, where several five star resorts are under construction. Presently, the landmark is the Four Seasons, which has two reputable restaurants: re Asian Cuisine is in the high bridge of the H structure, from where you get a great view of the city, and Cut by Wolfgang Puck is the place for meat.

Manama is home to many chichi restaurants. I strongly recommend Lumee (Bahraini), Dar Noura (Kuwaiti), and Um Sherif (Lebanese) in the Avenues Mall as well as Villa Mama’s (Bahraini) in Al Markh.

However, Manama’s culinary and nightlife district is to the south-east, in the unromantically titled Block 338, more poetically known as Adliya neighbourhood. Since it emerged in a sleepy residential area in the 1990s when the licensing laws were initially relaxed, this has been the country’s coolest vibe with dozens of bars and restaurants, most with tables and chairs spilling onto the pedestrianised streets. This is the antidote to the high-rise hotel staples found elsewhere, and though it is gentrifying with larger chains recently starting to replace the smaller boutiques, this is still where the kewl kids go. There are far too many places to reference, but particular favourites include Fusions By Tala (Bahraini), Gunaydin (meatery), Lanterns (curry house), and Masso (Mediterranean).

Of the other tourist attractions in town, the most prominent is Bahrain Fort, dating from the sixth century and the country’s premier UNESCO World Heritage Site. It is set on a hill off Qal’at Al Bahrain, the ancient harbour and former capital of Dilmun. There is a very nice walk around the moat, with striking views off to sea, and at the museum the excellent GB Cafe has a lovely terrace and garden.

Al Khamis mosque was the first built in Bahrain, dating to the eleventh century, though the twin minarets were added in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. It is very close to a large burial ground, which now has an equally large extension just for those who died of coronavirus; both areas are distinctive because of the local custom of flying flags over the graves, and both are usually buzzing with people come to visit their loved ones, especially on Fridays.

The main centre for prayer is Al Fatih Grand Mosque, one of the biggest in the world when it opened in 1988. It holds 7,000 worshippers over its 6,500m2 and non-Muslims can visit it from 9am until 4pm except on Fridays.

Near it is the Supreme Council for Islamic Affairs and the Isa Cultural Centre with ornate massive petals on its roof, and not far away is the Beit Al Quran, one of the most renowned Islamic museums in the world. Here there is a significant collection of Qur’anic manuscripts, some dating as far back as the first century Hijra, 700 AD.

Rest of Bahrain Island

There is a simple route around the rest of Bahrain Island to tick off what sites of interest are there. It is easy to rent a car or hire a cab to do it in a day, making stops not at all far apart.

Heading out of Manama west and south you will drive past compounds of brown concrete villas-behind-walls that are the basic builds of the whole region. First up are a couple of sites of temple ruins – Barbar and Saar – that are important archeologically, if not on the standard tourist itinerary, and to find them you may need to ask the locals to point the way.

At Barbar, you will see an area that has been cleared for parking hundreds of cars, and a state-of-the-art visitors’ centre, all incongruous as you will almost certainly not find a single other person at the small pile of rocks spread around. This is the site of three early Dilmun-period temples built from limestone rocks on top of each other, all to worship Enki, the god of wisdom and freshwater. The oldest dates from 3000 BC, the next two were added at 500-year intervals.

At Saar – where you need to drive off-road for five minutes at the end where the sign points – are the ruins of a temple dating from 2000 BC that is believed to have played a part in marking the summer solstice. Here you will find only wild dogs, though the honeycombed foundations are at least intelligible to the lay eye.

About 20 minutes’ drive south-west from Manama are the A’Ali Royal Burial Mounds, the country’s second UNESCO World Heritage Site, dating from 4,000 years ago. Oddly, here there is no kind of border fence never mind a car park and a visitors’ centre, so you just drive up and walk about. In all, there are twenty-one separate Dilmun-era burial grounds across Bahrain, containing almost 12,000 individual tumuli, though these are the most significant because of the status of their inhabitants.

Heading down the centre of the country, the city of Riffa was the seat of government until 1869 and its fort was the home to nineteenth century ruler Sheikh Salman bin Ahmed and his heirs. The fort has been carefully renovated and its Raazji Bahraini restaurant has a terrace with fine views across the Hunanaiya Valley.

To enhance their global prestige and to attract first-time visitors, governments in the Arabian Gulf have for some time been falling over themselves to host major sporting events. This all began in 2004 with the Bahrain Grand Prix, which has become a firm fixture in the F1 calendar, a night race that often raises the curtain on the new season. It has been contracted to run to at least 2036.

Bahrain is so proud of its Grand Prix, which is such a big deal in such a tiny place, that it has almost come to define its modern national identity. The arena itself is small and cute, and it all feels much less of a circus than other Grand Prix, though it is nicely done with coffee shops and souvenir stalls set around the main grandstand. It is one of the easiest races in the Formula 1 calendar to get tickets, which can even be available on the day of the race itself as it never sells out; they can be booked from the Circuit.

Outside of race weekend, you can take tours of the circuit and even have a Dragster Experience on the track. There is also a Karting Circuit next door that takes walk-in would-be racers.

At present, the nearby horseracing course, a thin circle of green grass lined by white rails in the sandy desert, feels a bit small-time, with a little car park and a little grandstand. However, leading international owners, trainers, jockeys and horses have recently been attracted by the Turf Series held from December to February, with the chance to enjoy early run-outs before returning for the flat season in Britain. The Parade Ring is full of elegant royals in golden ghutrah, while the neighbouring forecourt is packed with young men quite happy to throw a few punches after each race if they feel cheated in their bets; gambling is illegal at the track but there is plenty going on for sure.

Going south from here you really are into the empty desert. For miles, occasional oil fields and several military bases are about all there is amid the beige rocks and sepia sand. At Dar Al Naft there is a small oil industry museum right next to the sign by a hole in the ground marking the spot of Bahrain’s – and the Gulf’s – first oil well.

In the middle of this arid landscape, seemingly miraculously stands a 10m-tall acacia tree. It is known as the “Tree of Life” because for over 400 years it has grown all alone on a barren hill in the Sakhir desert, almost never feeling raindrops, but with unseen roots that stretch 50m below the ground into the water table. It is heavily plugged in guide books, some of which bizarrely claim this to have once been the mythical Garden of Eden, and consequently it is visited by as many as 65,000 tourists every year. Mystical, man.

It takes barely an hour to drive directly from central Manama all the way to the south-east tip of Bahrain Island, where almost nobody comes except for the expat residents of Durrat Al Bahrain. This is a vast gated community on a series of artificial islands shaped like horse-shoes that is clearly crying out for David Lynch to lift the lid on its plastic paradise of identical cream villas, manicured lawns and ponds laden with black swans. Typical of the new Gulf. Each villa has its own jetty for jet skis and boats, and it is only 25km from here to Qatar. It took me a while to charm the security guards to let me in just to see the oddness.

Back up the west coast, close to the start of the bridge that connects Bahrain with Saudi Arabia, and not far from the Sofitel Hotel where the Formula 1 drivers all stay during the Grand Prix, is the Royal Camel Farm. Open from 7am to 5pm for anyone to wander around, there are scores of dromedaries tethered to their spot, basking in the sun and waiting their turn to appear in the next ceremonial parade.

It was the opening of the King Fahd Causeway in 1986 that caused Bahrain to switch from driving on the left, as in its legacy imperial power Britain, to the right, like its contemporary partner Saudi. It takes an hour to cross the 25km because of course there are a couple of border stations to navigate. Most of the traffic is incoming as many Saudis have long used this passage to retreat to Bahrain for weekends of illicit fun and games. Though this flow largely dried up during covid, badly hitting the local economy, it is back in full swing now. On either side of the border are identical Observation Towers with views across the whole scene, though they are tinged by the green glass.

Muharraq

The historic district of Muharraq city, on its eponymous Island north-east of Manama, has been immaculately restored and is assertively marketed for its “Pearling Path”, which completes the national hattrick of UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

The regional pearling industry was led by Bahrain and dominated the Gulf economy for the better part of 2,000 years. Its boom time was between the 1850s and the 1930s, when as many as 30,000 divers sought gems thought more precious than diamonds. It collapsed after oil was found in 1932, also the year that the country’s capital switched from Muharraq to Manama. Today, there is still a bit of diving for natural pearls, mostly for tourists, but the trading of cultured pearls is prohibited.

The cultural heritage of this golden age is preserved in the seventeen bright white coral stone buildings that stand along the 3.5km maze of the Pearling Path, many of which have the feel of authentically renovated boutique hotels. You can buy a ticket for 1 dinar at the House of Abdulla Al Zayed to access them all. The standouts include the House of Sheikh Isa Bin Ali, who ruled Bahrain from 1869 to 1932, and the House of Siyadi, a leading pearl merchant, both of which give an idea of elite life at that time. There are several public squares and cafes, the pick of which is the Bu Khalaf Coffee Shop with its lovely terrace.

The UNESCO World Heritage Site also includes three offshore oyster beds, part of the seashore, and the Qal’at Bu Mahir fortress on the southern tip of the island where boats loaded with divers used to set off. To get to the fortress you must take the lift to the bridge that goes above the prohibited land of the Coast Guard HQ.

Nearby Arad fort was built in the Islamic style in the fifteenth century for the protection of this whole valuable pearling territory against the Portuguese. It was originally on a separate islet of its own before it was joined to Muharraq.

Dive Bahrain is an underwater theme park off Muharraq, with 100,000m² of artificial coral reefs, artistic sculptures and a sunken Boeing 747. There are four dive centres that arrange trips: Dive Vision, Extreme Sportz, Scuba Life and Scuba Master. However, after half-a-dozen attempts I am yet to find the site open, as it seems to suffer bad weather and serious accidents. I refuse to give up, and one day I will get there.

Other Islands

Of the remaining 80+ islands, not that many are of interest to visitors. Jarada, which is no more than a sandbar that is repeatedly washed away by the rising water, is popular at low tide among picknickers and snorkellers. There are several private operators that run boat trips out towards Qatar, past a series of ugly industrial plants but through deep blue waters broken only by rolling dolphins.

Al Dar does have facilities for day-trippers, even if its wooden loungers and tumbledown restaurant are a little low rent. It also has a lovely relaxed atmosphere on its little curved beach where women in bikinis sipping piña coladas rub shoulders with women in burqas holding their children. Furthermore, it is much closer to home, taking just eight minutes in water taxis that leave from the dhow harbour at Sitra fishing port. To be allowed on board, the Coast Guard will need to see your passport.

The Hawar Islands are ideal for birders as there are several species of international importance, including falcon concolors and fish eagles. All but one of this mini-archipelago, less than 2km from the Qatari mainland, have been Bahraini since they were first surveyed in the 1820s. They are uninhabited except for a police garrison and several hotels on the main island, and access to the others is severely restricted.

Bahrain has long hoped to build a 25km bridge to Qatar via the Hawar Islands, mirroring that to Saudi Arabia, so the entire region would be linked by road. However, this ambition has not yet recovered from the recent boycott of Qatar so you still have to take a 50-minute boat trip (from Durrat Marina Yacht Club) to get there and no further. As the whole region awakens and realises its future is likely to be better with greater cooperation, finally fulfilling this dream feels like it would be an important statement of modernity.