April 1998. Pol Pot was sitting alone in his secret mountain hideout listening to the radio. He was, ironically, a big fan of Voice of America. The news came over that his former Khmer Rouge allies had agreed to turn him over to an international tribunal. A few hours later he was dead. Suicide or heart failure? There’s enough internet speculation about that to power Phnom Penh. But in that one moment everything changed for Cambodia.

When I was growing up, Cambodia was a name synonymous with genocide. A name used by the US punk band Dead Kennedys in 1980 to encapsulate all that was worst in the world.

It’s a holiday in Cambodia

It’s tough, kid, but it’s life…

Yet now a holiday in Cambodia is a reality for almost five million travellers a year. With one of the wonders of the world, Angkor Wat, that’s hardly surprising. And there’s a hell of a lot more to it than the famous temples.

Getting off the beaten track you can really see and feel a thousand years of history; how it was shaped by ancient rivalries to how it is embracing twenty-first century culture. And, on top of all that, enjoy some of the most perfect beaches in South-East Asia.

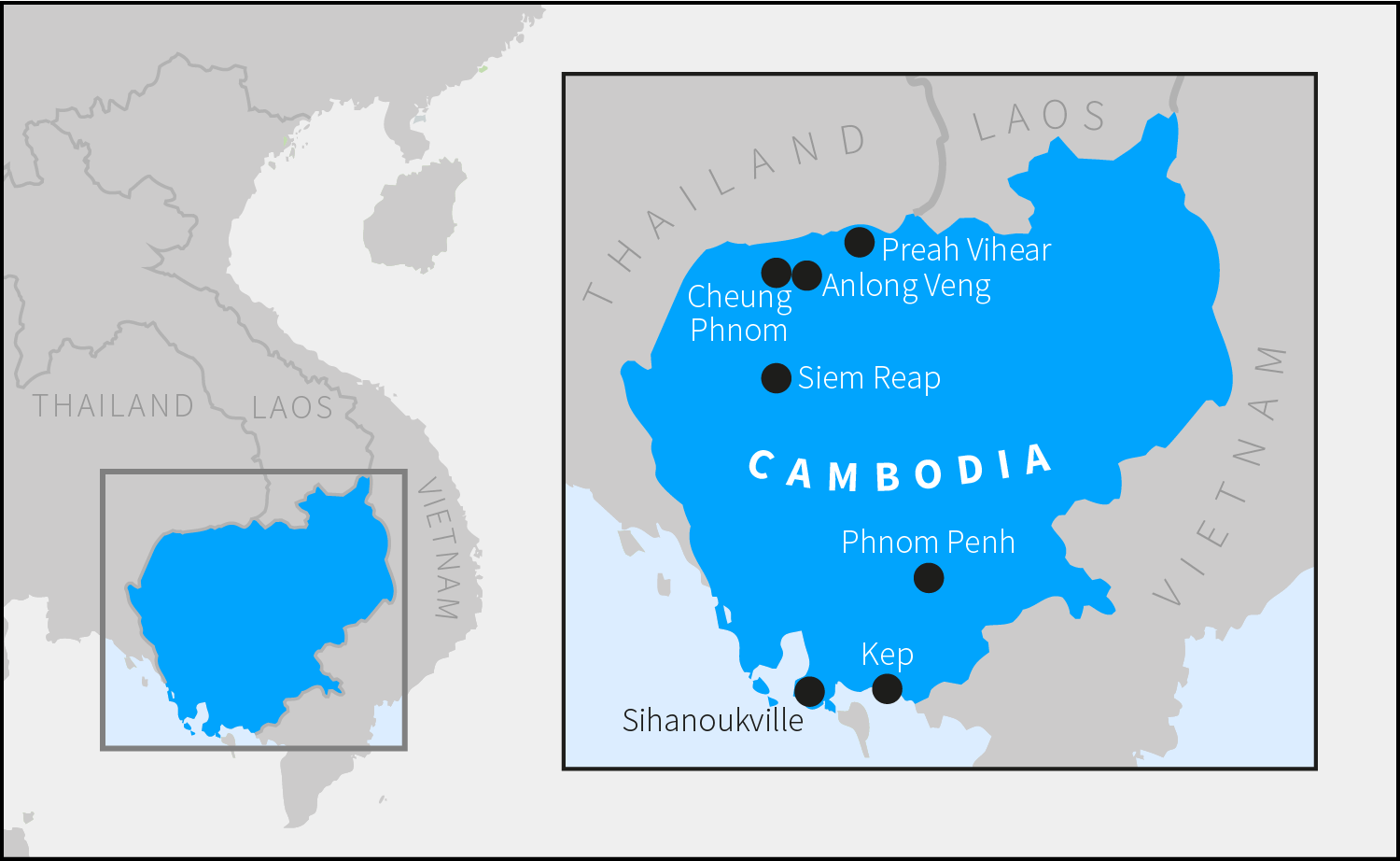

The North: Preah Vehear, Anlong Veng & Cheung Phnom

Siem Reap is the tourist town that’s grown up since 1998 to service the famous Angkor Wat complex. It’s also the jumping off point for a day trip where you can double-dip into some of the country’s most controversial recent history. The easiest way to explore the far north of Cambodia is to hire a car and driver (there are many reliable travel agents and tourist offices in the old market). The journey to Preah Vehear takes about four hours, covering just over 200 kilometres of pretty nondescript countryside on relatively good roads.

You drive to the foothills of the Dangkrek Mountains, the verdant range separating Cambodia from its bigger, richer neighbour, Thailand, and park up at a hut signposted “ticket office”. It’s here that you get the permit needed to visit the eleventh century Preah Vehear temple that’s been at the heart of a violent border dispute lasting over a hundred years … and one that’s still rumbling on. Permit in hand you are ushered into an old vehicle, like a cross between a pick-up truck and a jeep. You sit in the bone-jarring seats at the back, and bomb up the mountain to within 100 metres of the Thai border. Suddenly you see a lot of soldiers.

From the car park, it’s about another half a mile up to the temple complex. The remains themselves are nothing to compare with the crumbling splendour of Angkor Wat, but in atmosphere, location and sheer remoteness they win hands down. This is not a temple where you find yourself surrounded by dozens of Chinese tour parties taking selfies. Instead you sit, entirely alone, at the top of a sheer cliff; on one side you look back into Cambodia, and at the other you stare straight into Thailand. It’s immediately obvious how this temple has stirred up issues.

For more than a hundred years this remote set of ruins has been the flashpoint for a major international dispute. Since cartographers in the early 1900s marked Preah Vehear over the other side of the border, Thailand has refused to accept it as Cambodian and has continued to dispute numerous International Court of Justice rulings ever since. Things flared up big time when Cambodia applied for a UNESCO World Heritage listing in 2008. Thai nationalists wanted it to be a joint Thai-Cambodian listing. Cambodia, well, didn’t. Troops built up on both sides of the border and sporadically fighting breaks out. Even as recently as 2011 a number of soldiers died in clashes, although things have largely been quiet for a couple of years.

When we visited we found a trouble-free, pastoral scene. So we juddered back down the mountain in search of something more controversial.

Back in the hire car we retraced our steps for about 50km and within an hour were driving around a town called Anlong Veng. From 1979, when the Vietnamese drove into Phnom Penh and drove out the Khmer Rouge, this remote backwater served as the unlikely stronghold of Brother Number One and his fugitive cohorts. Right up in the mountains there’s an old outhouse where Pol Pot holed up in his most difficult days, but it’s hard to find someone willing (and able) to make the journey into the mountains to reach it. Not everyone wants to test the theory that all the landmines in the area have now been cleared.

More accessible is the old Khmer Rouge HQ and Ta Mok’s house. Brother Number Five directed the worst purges of the short-lived Democratic Kampuchea, earning himself the nickname “The Butcher” in the process. Ta Mok was the last remaining Khmer Rouge leader at large in Cambodia (he died in 2006), and his compound remains pretty much as he left it the day he was captured back in 1999.

Wandering around his old house among the trees is an unsettling experience. It’s not much of a stretch to imagine the horrors perpetrated in and around these bare wooden rooms. There’s even an old Khmer Rouge van, which doubled as Pol Pot’s mobile radio station, parked outside. (Whether for atmosphere or because they just ran out of petrol it’s hard to know in these parts.) When it dawns on you that the people sitting around staring at you are all ex-Khmer Rouge you realise it’s probably time to move on.

Just a few kilometres north-west sits Cheung Phnom Village. In the years since Cambodian forces ended the Khmer Rouge resistance, time hasn’t completely stood still. Ta Mok’s house might look the same, and the country might still be a one-party state, headed by a former Khmer Rouge communist leader, Hun Sen, for the last twenty-five years, but there’s something new in the air here: global capitalism. For as you turn into this border village the first thing you see, standing more than ten stories tall, is the Sangam Casino and Hotel.

Cambodia might have won Preah Vehear but this modern day temple belongs to their neighbour, as it’s been built so that rich Thais can come across the border to gamble and buy cheap whisky. The casino floor wouldn’t look out of place in Vegas. Table after table of largely automated roulette and card games are inhabited by Thai gamblers. But our attempts to join them fell flat. We had no Thai baht. Cambodian riels were useless. We discovered that the whole place, despite being in Cambodia, is off limits to its people. It’s illegal for Cambodians to gamble.

Nowhere does Cambodia’s peaceful present collide more vividly with its gruesome past than in the street outside the casino. Just twenty yards away, dwarfed by the massive new building is a hand-painted blue sign. Badly spelled, but obvious in what it’s trying to indicate: “Pol Pot’s Creamation”.

You follow the sign down an alleyway behind the village houses. After paying off the old man at the entrance, a former acolyte who guards the area from a fold-up chair in the shade, you access Pol Pot’s gravesite. The old man takes down the chain to let you wander across the dusty backyard to a rusted, corrugated iron hut: the cremation site, where his ashes have rested since 1998.

It’s hard to believe it’s here at all – as a would-be tourist attraction, and with occasional sympathetic mourners. And it’s hard to think of a more unprepossessing end for one of the architects of twentieth century history. A life that led to the death of more than a quarter of Cambodia’s population (more than 2 million people) between 1974 and 1979 is commemorated by a patch of earth marked off by some old concrete and cheap, blue plastic sheets. And another misspelled sign: “Pol Pot was cremeted here”.

Since we visited, the government has announced plans to turn Anlong Veng into a major tourism centre. They claim that at least eighty former Khmer Rouge officers are being trained to become tourist guides. They’ve got a long way to go. For now only around twenty tourists make the trek each month. We were the only ones that week.

Driving south from Anlong Veng back to Siem Reap, the only other tourist stop is of a more conventional kind. Apart from genocide the one thing the area is known for is its woodwork. The intricately carved wooden furniture you see in all the top boutique hotels in Siem Reap is likely to have started life here, in the hands of Khmer Rouge craftsmen. We wait by the side of the road for a couple of hours while our driver chooses a table for his home, and gets it finished off with woodstain. As we hang about for it to dry, night draws in and we still have three hours left on the road when we discover one salient fact. It won’t fit in the boot. We eventually have to leave without it.

The Coast: Sihanoukville & Kep

A flight south from Siem Reap to Sihanoukville takes only fifty minutes and costs just $70 but feels like you’ve headed a million miles from Cambodia’s dark past. For when you land you find yourself in a tropical beach playground. Comprising a small town centre, a few miles of coastline and two inhabited outlying islands, Sihanoukville is developing into a beach destination with something for all travellers.

Ignore the main beach, Ochheuteal, and the islands, Koh Rong and Koh Rong Sanloem, unless you’re looking for a backpacker experience. Instead, head a couple of kilometres out of town to the region’s most upmarket beach, Otres II.

You’ll find a mile or two of perfect white sand fringed with palm trees. Tiny deserted islands dot the horizon across still, turquoise water. Standing every fifty metres or so there’s a beach hut or thatched bamboo bar. Each has a handful of loungers. Behind the beach, a dirt track and a handful of shops. And behind the road, a row of places to stay, ranging from cheap cottages to brand new small hotels to a few beautifully appointed huts. (There are cabanas on the beach itself; but there’s no hot water or A/C on the beach side of the road.)

We stayed at Elephant Garden, a collection of boutique rooms and thatched cabanas. On the beach they have a fantastic bar/restaurant. European owned, the quality of food (our Xmas dinner was marlin steak and beef carpaccio), high-end wine cellar and a decent cocktail list raises it above its neighbours; though we’d have to say the quality of food, drinks and ambience right along the beach is hard to beat. $10 gets you dinner, booze and good wifi for the whole night.

If you can’t see yourself staying anywhere that isn’t lifted straight from the pages of a design magazine then try Tamu, an all-white Asian-styled retreat. There’s just 12 rooms and a lap-pool, complete with chill-out sounds, and a beach lounge whose candlelit transformation at night is wonderfully atmospheric.

With the three biggest hotels in Otres II about to open in the next year it’s probably a good place to go sooner rather than later. The ecosystem and fragile infrastructure looks like it could only take so much expansion without its perfection being lost. But right now it is pretty much the quintessential tropical beach. The only hawkers interrupting your daydreams are local women offering inexpensive massage and pedicures without you having to get off your beach loungers. You get used to taking one every day.

For a more traditional spa experience and holiday shops you’ve got the town at Ochheuteal, about fifteen minutes away in a tuk-tuk. The beachfront barbecues are surprisingly decent and it’s much less of a tie-dye, full moon party vibe than you’d expect, though if you stay too late the disco soundclash of the cheap rave scene gets going.

When you can rouse yourself sufficiently from your beach sun-lounger, grab a $50 taxi drive around 70km east to Kep-Sur-Mer to see a different aspect of Cambodia’s coastline, and get a glimpse of Cambodia’s more gracious colonial past.

Kep was the seaside retreat of the French elite at the start of the twentieth century, and by the 1960s was a St-Tropez-style ultra-fashionable resort. It fell into ruins in the Kampuchea era as the whole area was forcibly evacuated. Now it’s being slowly restored bit-by-bit and lush, newly-renovated, colonial villas sit side-by-side crumbling bullet-ridden shells of modernist architecture.

There’s a grown-up, quiet vibe but not much of any town or resort yet – or even beach. Just a few hotels and apartments spread out back from the water into the green rolling hills.

The focal point, if there is one, is the Crab Market. This is a 100m line of rickety wooden shacks leaning out over the sea, housing bars and restaurants as well as the actual market. These days Kep is most famous for its crab. Pepper crab. Cooked with the region’s highly-prized Kampot peppers. Our favourite Crab Market restaurant was La Baraka. A smart, French-tinged sea-food menu and two outdoor terraces over the water mark it out, as there was always enough space to get some peace and quiet to enjoy the moonlight hitting the still waters of the Gulf of Thailand.

The best tip is to stay within walking distance of the Crab Market. The top place (if you want to pay top dollar) is Knai Bang Chatt Resort. A stunningly restored collection of villas on the water, plus bar, sailing club and high-end restaurant, you’re looking at shelling out around $300 a night here. For a fraction of the price – $60 – and even closer to the crabs, we stayed at Le Ponton, a new French-owned and run hotel with a dozen rooms, a lounge bar and a swimming pool.

For a beach, people hop on over to Rabbit Island (Koh Thonsay), named because its outline resembles a rabbit’s face. Your guest house or any local bar can arrange the 20 minute trip for a few dollars. Rabbit Island is low on frills but ultra-chilled out. You could walk around the circumference in a couple of hours, Robinson Crusoe style, but most people find a lounger or hammock near to the beach where the boats drop off and just flop. You’re never more than 50 metres from someone who’ll fetch you a coconut, a rum punch or a massage.

When you’re back on the mainland the next and final step is to take a taxi away from Kep to the capital, which will set you back about $70 and take two-to-three hours. And from here you step right out from colonial reveries into what Cambodia is today.

Modern Day Phnom Penh

If the name conjures up any images at all they’re probably linked to Year Zero, 1975, when the Khmer Rouge moved in and tried to wipe out the city’s entire history, or from the film of the Killing Fields. Something involving helicopters circling white villas, while hundreds of despondent residents trudge away through heavily policed streets, no doubt. But Phnom Penh is finally starting to move on from that era.

Trying to make a modern capital city from the ruins of Phnom Penh obviously hasn’t been easy. When the Khmer Rouge were forced out in 1979 what was left was said to resemble an apocalyptic wasteland. Animals rather than people roamed around the ruined government buildings, and the fierce fighting had destroyed much of what Pol Pot’s regime hadn’t itself managed to raze. To get a feel for that, of course you must visit the memorial and museum of the Killing Fields and the S21 school-cum-prison.

But while Phnom Penh can’t yet be said to be booming, a modern Asian capital city is definitely emerging. The hectic traditional street life – motorbikes, tuk-tuks, busy markets, steaming food-stands and downmarket tourist sex clubs – rubs up against a new paradigm: glass and metal skyscrapers, international hotels and fashion malls. Plans are already afoot to open a Rosewood Hotel some time in 2016 at the top of Cambodia’s highest building, the Vattanac Capital Tower. The skyscraper is still being fitted out but the top fourteen floors will house 148 rooms, an open air “sky bar on a cantilevered terrace”, over a shopping arcade featuring all those luxury brands you see in any big city.

But before this opens, the city’s most fashionable scene is centred around Street no. 240 (helpfully most of the city is based on a simple numbered grid system), right behind the Royal Palace. Stay at The Plantation, the coolest boutique hotel among a burgeoning number.

240 is a quiet, tree-lined avenue with the kind of hipster boutiques you’d expect to find in Sao Paolo, Salamanca or Shoreditch. It has everything from an organic deli to local fashion designers to gourmet burgers and a Prosecco bar. Undoubtedly the best buys to bring home are clothes made from bamboo by Bambou Indochine and especially the Elephant Brand bags that you see hanging up outside every good shop and market stall (they are made from recycled cement sacks by landmine victims).

For what else to do in the city try www.phnompenhpost.com.

With economic growth at over 7% a year since 2010, and the disposable income of the top 20% of Phnom Penh’s population up 74% since 2011, it’s a good bet that the gentrification of the capital will power on. Although it remains to be seen if such a small – and remote – capital city can really sustain the level of development the government has planned for it.

But for now when you visit you can’t forget the city’s tragic recent past, even as you enjoy experiencing its exciting present and sensing its hopeful future. When you head a few minutes out of town to the tiny airport, past the barrios housing some of the 90% of the population who still earn less than $4 per day, it’s pretty clear that there’s still a long way to go before tourists associate Cambodia with its killer shops rather than its Killing Fields.