Côte d’Ivoire, Ivory Coast, has had a violent recent history, so very few tourists come here, no doubt fearing for their safety. As a former French colony, its main appeal was only ever to French speakers, and almost nobody here parlays any English at all. Yet right now it is sufficiently stable that experienced travellers should not be deterred from accessing the principal wonders of this amazing country.

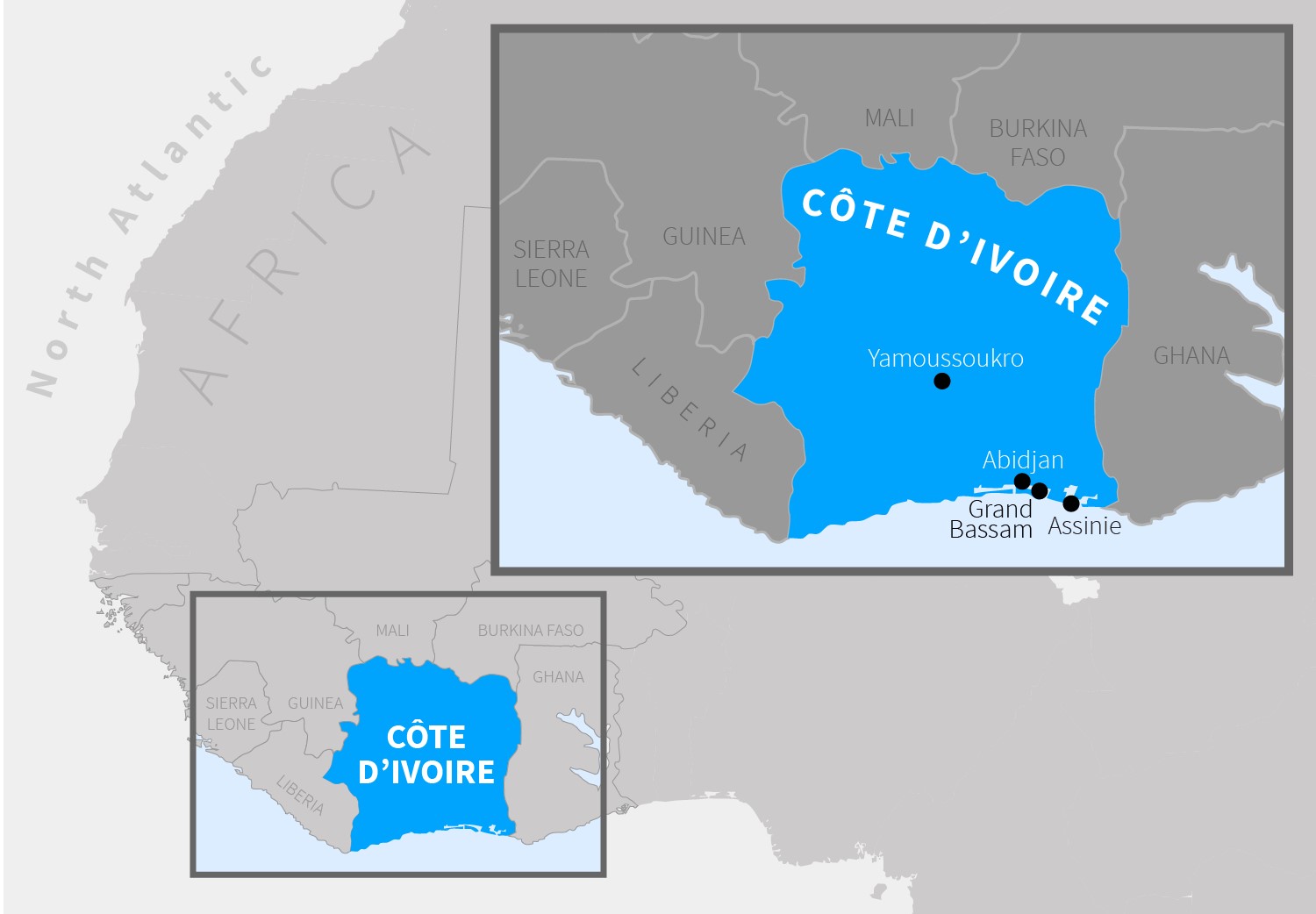

Current Foreign Office Travel Advice is to avoid altogether the western part of the country because of fighting between local militias. This means we can’t get to see the reputedly beautiful Parc National de Taï and its chimps, or reach the famed wood-carving tribes around the town of Man. One day. But in any case the main attractions are in the south-eastern corner, where we can enjoy the exciting party town of Abidjan, marvel at the world’s tallest basilica in very odd Yamoussoukro, roam the former colonial capital of Grand Bassam, and relax on the beach in one of the most naturally beautiful places on earth at Assinie. For a small country with a small reputation, Côte d’Ivoire packs a big punch and is full of knock-out surprises.

We entered the country by road from Ghana; it is a good three-hour drive from the border at Elubo to reach Abidjan, the capital in all but name. There are no direct flights from London, but there are plenty of connecting routes. Wherever you come from, you will need to collect a visa from the embassy, and to get that you will need to show them your yellow fever certificate.

Abidjan

Abidjan is set in a stunning natural topography: its six million people are spread around Ébrié Lagoon, which is linked by canal to the Atlantic just a few kilometres south. I was surprised to learn that Côte d’Ivoire had one of the fastest growing economies in the world in 2016 – 8.5% according to the IMF – and it shows in Abidjan. There is an impressive skyline of mostly 1970s high-rise buildings, with cranes currently constructing more. Sadly, we did not see this silhouette in its full glory thanks to the hamoutan: winds from the Sahara that occasionally fill the air with sand particles causing a hazy mist in winter (when it is dry and still over 30°C).

The statement hotel is the Sofitel, formerly run down but now fully renovated, standing proudly over the water in the wealthy suburb of Cocody to the east. This is where the local elite live, including the families of Premier League footballers. And where the foreign embassies are found, near the president’s domestic residence, with its yellow turrets at each corner featuring soldiers’ heads poking out above sandbags.

The other smart address is the Novotel at the bottom of Le Plateaux, the business district on a peninsula sweeping down from the north. There are great views from the terrace across the water between the bridges of Pont de Felix Houphouet-Boigny to the west and Pont de Charles de Gaulle to the east, major landmarks about a kilometre apart. (This is a great place to be on New Year’s Eve as just below is where the entire country seems to gather. This year the fun was enhanced enormously when almost 45 minutes after midnight the official PA system countdown and firework display caught us by surprise and suddenly kicked in, long after the streets were drunkenly rocking to local beats. It was gloriously chaotic.) Soldiers did storm the Novotel during the 2011 conflict to get at journalists hunkered inside; but, not surprisingly, these days all the big hotels have airport-style strict security checks.

In the west of Le Plateaux is Place de la Republic, not far from the president’s working residence. In the north is the national sports stadium, scene of several fatal stampedes in recent years, the Assemblee Nationale, flying scores of flags and circled by thousands of bats, as well as the modernist St Paul’s Cathedral, with very cool Africa-themed stained-glass windows. In the east is La Pyramid, a 1970s architectural icon fallen into rack and ruin. Nearby is a clutch of the very best restaurants in the city; these tend to have an authentic African ambience and decor, with a fusion of African and French cuisine.

To the north-east of the city is Le Deaux Plateaux. This is the middle class residential area with decent shopping, including Galerie d’Arts Pluriels, offering pieces from all over Africa, and the flagship stores of Vlisco and Woodin, high-end suppliers of the colourful costumes for women and men that are worn everywhere (cheaper versions are of course available in the markets). It is also home to a number of French-style villas turned into boutique hotels and excellent restaurants.

Yamoussoukro

It is 230 kilometres, two and a half hours on good duel carriageway, north-west towards Lake Kossou in the dead centre of the country, to Yamoussoukro, the family village of Felix Houphouet-Boigny. Houphouet-Boigny led Côte d’Ivoire to independence from France in 1960 and as the country’s long-serving strongman first president he egregiously decided to shift the capital here from Abidjan in 1983. Because he could.

A relative moderate, Houphouet-Boigny presided over what is known as the “Ivorian miracle”: exceptional economic success in West Africa in the 1970s. This was caused by maintaining strong ties with France – Francafrique – and by developing the country’s significant coffee and cocoa industries. However, it was followed by difficulties in the 1980s when commodity prices dropped sharply. (It is noticeable that even today the hotels all serve instant Nescafe, and it is very hard to find locally manufactured chocolate in the airport duty free shop.)

Houphouet-Boigny remained in power until his death in 1993, when he was succeeded by his deputy, who was overthrown by a military coup in 1999, presaging the country’s recent troubles.

In 2000, Laurent Gbagbo, a Catholic, was declared the winner of a hotly disputed election. After he survived a coup attempt in 2002, Côte d’Ivoire erupted in civil war, which lasted for two years, leaving thousands dead and the country split. Rebels, led by former IMF economist Alassane Ouattara, held the north. And Gbagbo the south, where he was accused of persecuting Muslims, immigrants from neighbouring countries, and Westerners.

Things were brought to a head by the 2011 election, which was regarded as free and fair by international observers. After Gbagbo refused to accept defeat, he was captured by UN- and French-backed forces, and transferred to the International Criminal Court in The Hague, where he remains, facing charges of crimes against humanity. Ouattara continues as president as an uneasy peace has settled on most of the country, which is trying to re-build.

As you arrive in Yamoussoukro, on the left hand side is the Hotel President, a brutalist 1975 structure with a weird 14th floor restaurant stuck on top like the bridge of a spaceship. Given our novelty as English-speaking white tourists, we were given an impromptu guided tour by the manager, including a peek at the US$1,000 a night president’s suite, a local Flag beer in the bar with its yellowing chandeliers and orange club chairs, and a look out from the panoramic observation deck at the top.

I freely admit that I had never heard of Yamoussoukro before I came to Côte d’Ivoire and so I had no idea what to expect. It was only as we were enjoying these views that I spotted the Basilica of Our Lady of Peace rising dramatically in the far off wilderness, and suddenly realised that there was a very impressive structure on our hands right here in the middle of nowhere.

Opened in 1990 by Pope Jean Paul II, this turns out to be the tallest basilica in the world at 160m, and costs are estimated to be equally high, as much as US$600m. Roughly modelled on the Vatican (140m tall), it stands on seven acres of European marble, and can hold 18,000 people in the nave with a further 150,000 in the courtyard. Oh, and to add spice, while we were there it had several white UN-logoed vehicles parked out front in case of emergencies.

You must take your passport to get in, and you should take the guided tour (in broken English) as it is rich in weird record-breaking statistics. The whole thing is a great hoot, all the more so for being unexpected. You can get up to the top, to look down on the chancel as well as across the village-cum-capital outside.

The other fun stop in Yamoussoukro is Houphouet-Boigny’s palace, visible though not accessible behind a large lake. Beyond that, hidden by trees, is his mausoleum. These are guarded by soldiers at an entrance across a narrow bridge.

The lake is home to scores of crocodiles, which are fed at 5pm every day. As I was taking a photo of three basking in the foreground with the palace behind, a man snatched the camera from my hands. He was bigger than me, wearing army fatigues, and waving a gun. He pointed me to a sign in French that simply told me that crocodiles are dangerous, but then he marched me across the bridge to the guards. I was informed that my camera had been confiscated. Though there was a very unpleasant air of threat, it soon became clear that they were simply shaking me down for a bribe. After about half an hour, they demanded 30,000 cfa (US$1 = 600 cfa) and we settled on 10,000 cfa. Our taxi driver, who served as translator during the angriest exchanges, was very upset at the damage he perceived this incident had done to his country’s image.

(This anecdote might help illustrate the mood of many soldiers in the country. This is germane because a couple of days after this, soldiers mutinied at army bases across the country, holding hostage the defence minister, protesting at their poor pay and living conditions. Although on this occasion their demands were met, it is precisely in this way that the coup began in 1999.)

Grand Bassam

In the “Scramble for Africa” European powers were deterred from establishing permanent garrisons on this stretch of coast by the strong currents and the absence of sheltered harbours. Therefore, the slave trade had relatively little direct effect here. Of course, there was a short-lived market in ivory during the seventeenth century, but it died out within decades along with the elephants.

By allying with local tribes to ward off the British, the French finally established the by-now misnamed Côte d’Ivoire as a colony in 1893, and based its capital in Grand Bassam.

Grand Bassam is only half an hour east along Ébrié Lagoon from Abidjan, and it is really just a suburb of the city (though with a very different vibe). You pick up some fun-sized bananas and gigantic pineapples at the roadside markets and drive through the modern town, across the bridge and down to the French Quarter, which is the very cliché of faded glamour. There are only a handful of streets, but they are extremely pleasant for bimbling about.

There are several decent hotels and restaurants along the track by the coast, among which the historic place to be is Etoile du Sud. Behind the classic colonial façade are rooms with four-posters and rich-red wood furniture. In the enclosed courtyard is a manicured garden, a pool, and a restaurant above the beach. This was the scene of a random Al-Qaeda terrorist attack that hit worldwide headlines in March 2016 when 18 people were killed, including a number of foreigners, but these days there is heavy security front and back. (We had in fact been due to come here at that time, but after this incident we postponed our trip until now.)

As you can imagine, there are very few tourists around. It was really just us and the scurrying Rainbow Lizards (the males grow up to 30cm, have brilliant orange heads and tails, and do press-ups to attract mates). Yet it all felt very safe, even if we were on the lookout with more alert senses than usual.

The former French governor’s mansion is now the Musee de Costume National, which is virtually bereft of exhibits but is the best place around to buy antique wooden masks and statues.

The beach is pounded by roaring waves, and feels like a small town market, especially on Sundays. People pop down from Abidjan to promenade, and the local women respond by filling their baskets with anything that could be bought, placing them on their heads, and patrolling up and down looking for business.

Assinie

No matter how well one has travelled, one does not often come across a place quite as magical as the area around Assinie. Though Abidjan and Grand Bassam are in beautiful locations, they cannot compete with Assinie.

It is 45 minutes further east from Grand Bassam by car, though the local elite come here for weekend retreats by helicopter from Abidjan. From the town of Assouindé, a finger of land, mostly no wider than 100 metres, stretches into the Gulf of Guinea for 20km, creating a peninsula with strips of beach on each side, leaving a spine studied with palm trees hiding the luxury villas of the Ivorian glitterati.

This thin protrusion runs east parallel to the shore, so half of its beaches face the crashing open sea, and the other half the enclosed serene lake it creates. This inlet is about half a kilometre wide and runs the full 20km from Assouindé until it reaches the ocean. This natural barrage causes this entire stretch of water to be calm and still, but for the occasional boat putting up and down, or a rare canoe passing slowly with a fishing net off the side.

The lake meets the sea at the village of Assinie. Here, on the relaxed sandy streets, you can easily find a local to punt you around the water, either into the huge Aby Lagoon, surrounded by a national park with its forest of palms, or out to the mouth of the Atlantic. On the corner is the Assine Beach Club, surrounded by golden sand, where high society comes to party.

There are plenty of high-end hotels along the 20km length of the mainland shore, known as Assinie-Mafia, with views across to the lake, peninsula and ocean beyond. Many of these have been built since the 2011 conflict.

There are so many places to stay that are straight from the pages of Wallpaper, but we chose the Coucoué Lodge. This not only has great facilities (with chalets right on the water; an infinity pool with nearby beds under gazebos; an open-air restaurant on decking extending over the water, with excellent seafood, a very fine wine list including a Chateaux Margaux, and a humidor packed with Cohibas; jet skis for the lake and quad bikes for the peninsula; along with several tennis courts and a golf course), but also the cutest logo. On top of all that, they have a bar with sun-loungers over on the sandy strip as well. When we arrived, we were given a mobile number and whenever we wanted to go anywhere we just rang it and our own boat appeared as if by magic.

We had it all virtually to ourselves during the week, though wealthy Abidjaners flood the place at weekends. We also saw some white French tourists here; apart from a smattering at Grand Bassam, these were the only ones we encountered in our ten days in the country.

A note to the editors of guide books: I realise it is difficult but it would be good to check that your writers have actually been to the places they write about. Bland and general copy about exquisite Assinie might reveal this deficiency.