Like an onion, the layers of the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea are too many and too deep for tourists to see what is really going on, especially in the environment of the strictly policed tour that is required to visit the country as a foreigner. But you can pick at the surface, and you will certainly get to know the country as its officials wish to present it to the world, and this is more than sufficiently fascinating to make the accompanying frustrations worth bearing.

The only way to get through this trip to a country unlike any other on earth is to accept that you are not able to express your judgments: just learn, experience and quietly try to understand. It is an awkward and morally ambiguous position.

This is a travel review not a political commentary. Obviously, politics are omnipotent in North Korea; but, in so far as it is possible, I have tried to keep my reflections to my experiences as a tourist. To read about the real lives of North Koreans, albeit in the 1990s, everyone turns to Nothing To Envy, by American journalist Barbara Demick, on the impact of the famine that followed the collapse of the Soviet Union. For a glimpse into the inner circle try Dear Leader, Jang Jin Sung’s recent memoir of a propagandist forced to flee to South Korea. And for contemporary news and analysis a useful website is the Seoul-based New Focus International.

Some of what we are told during this tour is simply a lie. Other things are hard to verify and many are hard to believe. (You quickly develop a neat line of ironic exultations to answer your guides’ enquiries as to what you thought of such-and-such: it was “incredible” or “fantastic”, you will say, gamsahabnida.) I have faithfully reported here what we were told and shown.

The Kim cult and the thought-control are of course orchestrated from Pyongyang, where you will struggle to take in the immense scale of it all: the quantity of portraits and mosaics of the leaders; the heights of the statues and monuments; above all the extremity of the Mausoleum where the two late leaders’ bodies are presented to the public; as well as the effort devoted to the Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, related war memorials and associated anti-US, anti-Japanese and anti-South Korean mythology.

You will be shown what are thought to be examples of modern industrial efficiency and scientific advancement, like the catfish farm and the brand new SciTech facility, mesmerising in themselves. But there is a softer side too, where ordinary people play: picnicking in the park; at the circus; in the waterpark; at the first ever beer festival; and in the high-end spa. And there is a blizzard of daily excitements, including eating dog, dancing illicitly, and trying to figure out what that you are shown is real and what is fake.

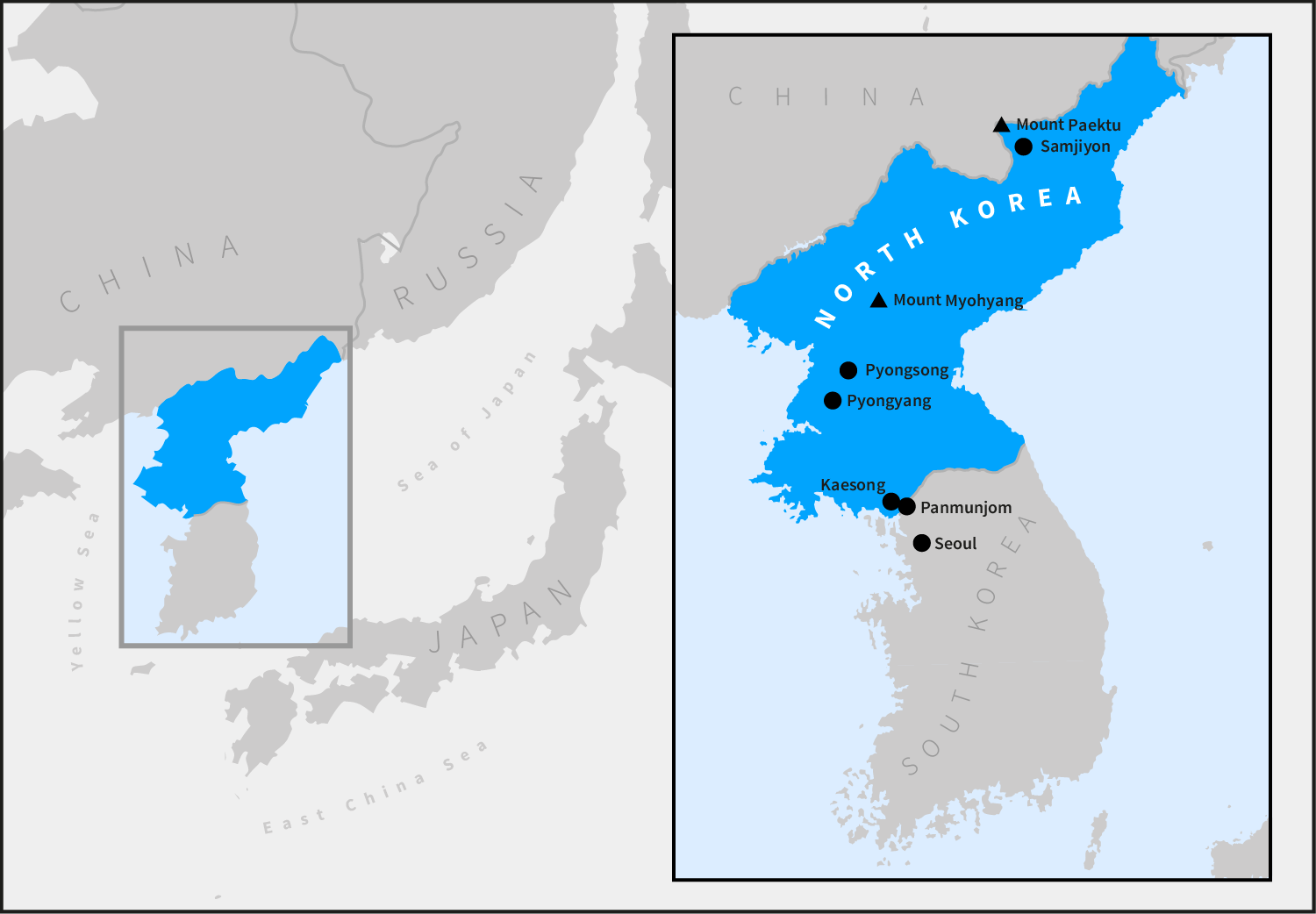

Outside the city, there is much to see too. A little to the north is a little-visited Buddhist temple in the beautiful forest around Mount Myohyang. In the far north is the totemic volcano of Mount Paektu. And in the south is the DMZ and one of the world’s most dangerous borders. All in all, this is an action-packed experience right from the get-go.

A Semi-Detached House in Chiswick

Nobody can get into North Korea, let alone travel around, on their own. You have to book through a tour company, and there are several based in Beijing. We chose Koryo Tours, set up in 1993 by a British guy who still runs it; they proved to be extremely professional. They have a relationship with the Korea International Travel Company, the state-owned set of buses, drivers and guides that will shepherd you around the DPRK.

They can sort your visa for you in Beijing, but then you are simply given a piece of paper which you have to give up when you leave North Korea. Or you can jump an extra hurdle and get it for yourself at home, in which case you have a glorious stamp in your passport to keep as a souvenir. We chose to go to the North Korean Embassy in Chiswick (where there are just five staff) to collect ours a few days before we flew out. Either way, it is a somewhat bureaucratic process.

Your tour company will set up a detailed itinerary for your trip. You can either join one of their regular circuits with a dozen or so other people; or you can create your own independent route, as we did. If you are thinking of going, I hope this review will give you an idea of what to ask to see (and if it’s not on the itinerary agreed in advance you won’t be seeing it as there is zero room for improvisation as you go along). The standard tours tend to last about a week; we decided this was a one-off, and I was celebrating my 50th birthday, so went for a full 12 days, which gave us the chance to experience life off the admittedly not very heavily beaten track.

The day before you fly out to Pyongyang you must attend a briefing session with your tour company in Beijing. This is where you will be told some basic dos and don’ts. You are strongly advised not to ask questions about: the Kim leaders; religion; nuclear weapons; traitors; or political prison camps. There are strict rules on what you can photograph. Any pictures of the leaders’ statues must be of the whole body not just a part such as the head; and they cannot be taken from beyond 45 degrees from the front-centre. There are to be no photos of construction sites, bus stops, cows in fields or a host of other things. You must never fold, tear or throw away any newspaper or magazine that so much as contains a photograph of one of the leaders (and they all do). And you must never point (though you will see literally thousands of photographs of the leaders doing it).

Contrary to rumour, you can take mobiles, tablets and laptops into the country. It’s just that they won’t work. And at the airport on the way in, your photos, videos, messages and other files will be rigorously searched and some may be deleted. So we decided to leave a lot of gear at the Koryo Tours office for collection afterwards.

About 5,000 Western tourists a year go through this rigmarole. That averages fewer than 100 a week, though in fact there are two peaks. First, at the time of the Pyongyang marathon on 15 April to mark Kim Il Sung’s birthday. (This has been open to foreigners for the past two years and has been deemed a great success. It attracts about 1,000 foreigners and 200 locals.) Second, for the Liberation Day celebrations on 15 August, which is when we were there along with at least 500 others. (Annoyingly, on that morning we were told that this year’s Mass Dances were postponed until 28 August, the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Socialist Youth League. That’s typical of North Korea.)

Into the Darkness

There is a definite frisson of excitement as the departure board at Beijing airport terminal 2 announces the flight to Pyongyang. We board an old Russian Tupelov in the colours of state-owned Air Koryo for the one and a half hour flight. It feels like we are leaving civilisation and entering two weeks of darkness, cut off from the world.

On board, we are entertained on the drop-down screens by a video of a military band playing at a huge concert. This turns out to be from the 70th anniversary of the founding of the Workers’ Party of Korea in October 2015, and the reason I know this is because the same footage is shown every afternoon on the state TV channel throughout our whole trip.

The first thing that jumps out at you are the badges. Every DPRK citizen from the age of 14 always has to wear a badge next to their heart with the faces of one or both of the dead Kim leaders. The next thing you notice is that nobody ever wears jeans.

We land at Pyongyang’s small but shiny new airport, where we have to declare our electronics and our books. Bags are thoroughly searched to make sure there isn’t anything else. Mobiles are registered. And files are reviewed. It’s all done with smiling civility; the rules all have to be complied with, but it isn’t in the least bit intimidating.

On leaving immigration, there are as usual lines of locals waiting to meet people from the plane. But there are no boards with our names scribbled on. Instead, two ghosts emerge from the throng and introduce themselves as our guides. We are escorted out to the waiting minibus (which we are proudly informed is made in the DPRK) and driver. They will be with us day and night for the next two weeks. Importantly, this means we are outnumbered three to two. And it also means that each of them will be able to report back on the other two.

Although charm can forge a relationship of sorts with people who in other circumstances would obviously be pleasant, they had clearly drunk the Kool-Aid so we quickly find it is not possible to build any trust with our captors. For instance, soon after we had fun playing pool with one of them in a hotel, he took my camera off me for a while, and then demanded to review the pictures I had taken. They hovered close at all times – outside the hotels it was very rare that we were allowed beyond touching distance for the whole trip, even during visits to the bathroom – creating an atmosphere of anxiety. They heard every whisper. They never forgot a word we said. And they were certainly never off duty. By the end of the first week, this intense scrutiny started to cause us to be a bit stir crazy. In the second week we were talking about Stockholm Syndrome. These are highly educated loyalists with perfect English; yet they told us that when there are no tourists to marshal they have to help bring in the harvest or lend a hand on construction sites.

The Fifth Floor

On the 23 kilometre drive south to Pyongyang our guides relieved us of our passports for the duration of our trip and we entered Alcatraz. The Yanggakdo Hotel sits on its own island in the middle of the River Taedong that splits the city east and west. Virtually all foreign tourists are stationed here. Not only are we not allowed off the island unaccompanied, we are not even allowed beyond the guarded grounds of the hotel. (In training for a marathon, I was restricted to running around the car park of the compound.)

Our room is on the 38th floor with amazing views across Pyongyang. We can easily see that there are virtually no lights in the city at night. There are several channels on the TV. Until three weeks before there was even BBC World, but that was removed after Rupert Wingfield-Hayes’ fairly fact-free but critical Panorama was broadcast. Now the only foreign news channel is Al-Jazeera.

We saw Al-Jazeera nowhere else in the country but whenever we returned to Pyongyang we came back to the same room so we did get occasional news updates. It was very odd to have so little idea of what was happening in the outside world. Local TV is dominated by pictures of marching soldiers and Stakhanovite workers. We were there during the Rio Olympics, which were hardly mentioned. The only coverage we saw was of a DPRK table tennis player receiving her bronze medal. It was almost a week after the event before we knew that Usain Bolt, probably the most famous sports star on the planet, had won the 100m gold. However, we did see on Al-Jazeera reports of the defection to South Korea of the DPRK Deputy Ambassador to London, as well as news of several North Korean nuclear missile test-launches in the Sea of Japan.

In the hotel lift there is no button for the fifth floor. This is the cause of all kinds of speculation among tourists. And this is where an American 21-year-old student recently crept up the stairs, stole a flag from the walls, and got 15 years of hard labour for it. We assumed at all times that our room was bugged, and we heard reports from other tourists that their luggage had been rifled. You know before you go that North Korea is the Truman Show meets 1984 but nothing can prepare you for the reality of that.

The Kim Cult

Current North Korean national legend is very easily summarised. The Koryo Dynasty, between 918 and 1392, unified the peninsula. This was followed by what is called “feudal rule” until 1910, which was ended only by Japanese occupation. The Great Leader Kim Il Sung was born in 1912 (this is effectively year zero, the date that starts the Juche calendar, making 2016 103; you see both dates everywhere). He began fighting against the Japanese in the 1920s until he successfully overthrew them in 1945, when he set up the Workers’ Party of Korea. As the country was divided by Soviet-American deadlock along the 38th parallel, he became Prime Minister of the socialist north. He then defended the DPRK from US invasion in 1950 before defeating them in 1953. And history seems to more or less stop there.

There are two guiding philosophies. The Juche Idea, which is a code of self-reliance (for the country not for individuals of course). And the Songun Policy, which means “army-first”. Both are talked of endlessly.

After Kim Il Sun’s death he was succeeded in 1994 by his son, the Dear Leader Kim Jong Il, who in turn was followed in 2011 by his son, the Supreme Leader Kim Jong Un. (The public is not told when he was born, how he was educated or where he lives, though they do know he smokes.) The three Kims are revered as gods and the deceased pair in particular are mythologised obsessively.

The most obvious expressions of this are the giant identical portraits, with their benign countenances, outside every public building across the country (each home also has to display the same two photos inside), the colossal mosaics at the side of roads everywhere, and the gargantuan statues in public squares and the foyers of everything from factories to swimming pools.

The biggest statues, at 20m tall, are the Mansudae Grand Monument in the centre of Pyongyang. There is a runway leading up to them from the River Taedong about a kilometre away. To the left there is a huge monument to war against Japan; to the right one against America. (This is very close to the iconic Chollima Monument, which symbolises the advance of the socialist society.)

People come from all over the country to pay homage here (everyone has to bow before these and many, many other statues and pictures). As we arrived, hundreds of villagers were waiting their turn. They were obviously not familiar with foreigners because as we walked past them every pair of eyes followed us every step of the way. We then watched them lay the national flower – the magnolia, which is often seen surrounding mosaics of the leaders – and line up to bow in sync. It is a shocking sight (though it is equally shocking how quickly you get used to it). We had to do the same.

On the western outskirts of the city, we are shown the Mangyongdae “native house”. This perfectly preserved village dwelling, alone in the forest now that every other building has been cleared, is supposedly where Kim Il Sung was born and raised until the age of 14 when he went off to fight the Japanese.

The other end of this story is told at one of the most awe-inspiring tourist attractions on the planet: the Kumsusan Mausoleum. The residence of Kim Il Sung during his lifetime, a 30 minute drive north west of Pyongyang, has been turned into the tombs of Lenin plus Mao multiplied by Gracelands then subtracted from however you used to think the world works, and is now the vast vault where Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il lie embalmed in glass coffins.

It is open to foreigners only on Sundays when locals have to wait until we have all entered. For men, it is compulsory to wear closed shoes, trousers (not jeans) and a shirt collar (a tie is merely desirable); for women, shoulders and knees have to be smartly covered. We walk in crocodile formation, headed by our more than usually jumpy guides, one tour group at a time, through the machine that cleans our shoes and the wind tunnel that blows dust from our clothes. Then we are not allowed to walk at all as it is thought disrespectful. Instead, we have to stand on a series of travelators and escalators that transport us at least 1,000 metres past hundreds of titanic portraits of the two leaders (typically with one of them pointing to the far distance while lackeys appear to take down their every word in open notebooks), past dozens of female sentinels (all in their mid 20s, with identical uniforms, identical physiques and even identical haircuts), while we listen to music (we are told that the two songs on an infinite loop are Kim Il Sung Will Always Be With Us and Kim Jong Il Will Always Be With Us).

We are deposited in a massive marble gallery, which leads to another, and another, all adorned with the same kinds of photos and sentries. There is another wind tunnel. Then we finally enter the chamber smothered in red neon light that contains at its centre the glass coffin within which Kim Il Sung is displayed. One group at a time, we file towards the feet and bow, walk clockwise to the left hand side and bow again, then walk around the head to the right hand side and bow yet again. When we exit we are confronted by several halls containing Kim Il Sung’s train, cars and other possessions. On another floor, the exact same rooms are replicated for an identical experience at the tomb of Kim Jong Il.

The whole route takes about three hours to complete and as the foreign tourists exit on the moving-walkways, swapping notes on the astonishing experience we have just had, on the opposite travelators come the locals: deathly silent, rock still, zombified. The men in white shirts and red ties, the women in gorgeous balloon dresses, they have come to mourn.

The Party Line

We were told that every home has a radio concreted into the walls that comes on automatically each morning and evening to blast out music, news and propaganda that cannot be turned off. Revolutionary songs, often allegedly composed by Kim Il Sung or his father, are blared from official vans that drive around the streets, as well as piped into public squares, hotel lobbies and even train carriages on the underground system. Instead of advertising hoardings there are socialist realism posters all over the place.

There is what seems to be a fully functioning underground system, at least the parts that we saw. There are 17 stations along two lines in the west of the city. We travelled four stops through typically named stations. Starting at Glory, then Torch, Victory and Reunification, coming out at Triumph. The platforms are packed with commuters reading the day’s newspapers pinned up on display boards.

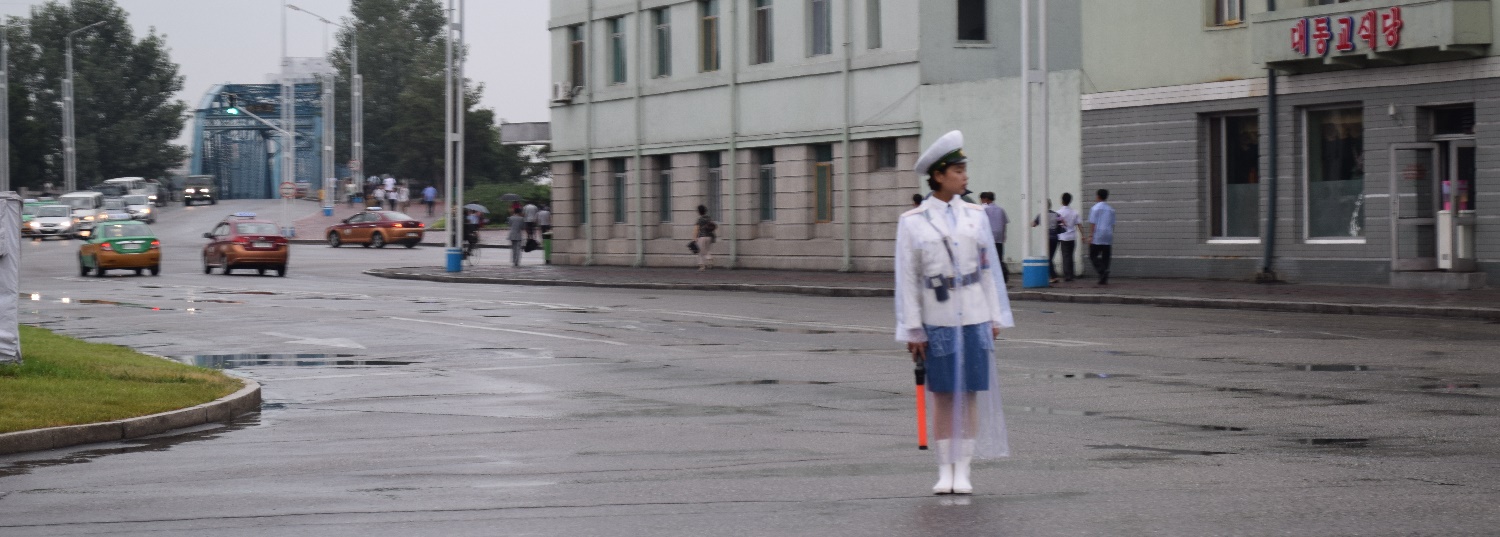

The very few cars on the roads are controlled by a series of “traffic ladies”: all are young, unmarried, dressed in matronly uniforms, and waving bright orange sticks. They are stationed at every junction in the city centre, robotically turning their feet and their heads to see in all directions, viscously whistling at anyone going a bit fast, and saluting at official party cars (about one in three; virtually all the others are taxis; old-fashioned bicycles and battery-powered cycles are more affordable and popular). Pedestrians have to use zebra crossings or risk losing their jobs.

Running parallel to the River Taedong all the way down to the Grand Theatre in the south west is the broad boulevard of Victory Street. We walked down it – one of the few places we were allowed to get out of the minibus except when visiting a specific building – and saw smoky bars packed with local men, along with a homeware shop and a hairdressers. This is also where soldiers goosestep and weapons parade on ceremonial occasions.

Victory Street cuts through one end of Kim Il Sung Square, the main plaza, surrounded by ministerial buildings and the National Art Gallery (this is notable because the paintings are presented with two dates: when they were painted; and when they were first seen by one of the leaders). Here we saw hundreds of people practicing their performances – singing, drumming and flag-waving – for the Liberation Day celebrations on 15 August. This included a number called Homesickness, which was by all accounts Kim Il Sung’s, and therefore the nation’s, favourite (a song written, obviously, by Kim Il Sung himself).

Opposite Kim Il Sung Square on the other side of the river is the red-flame topped 170m tall Juche Tower. There is a great view from the pinnacle, not least of the May Day Stadium, on a northerly island, with over 150,000 seats the largest sports arena in the world. This is the home of the Mass Games, when tens of thousands of citizens, after practicing for months, perform synchronised gymnastics and ballet to tell epic stories. It used to be held every August to October, but has not occurred since 2013. Instead, for Liberation Day and other public holidays, there is Mass Dancing, a smaller affair held in front of the singers in public squares. Also on the east side is the enormous party monument, a sculpture featuring the hands of a worker, a peasant and an intellectual.

At these and other sights, your tour guides hand you over to female “local guides”, all dressed alike (in traditional costume, which interestingly is the exact same dress you see at tourist sites in South Korea), with the same hairstyles (these vary in the South), whose job is to constantly reinforce the party line about the leaders and the socialist revolution as well as the imperialist aggressors from the United States and Japan and the puppet regime in Seoul. Nowhere does this happen more professionally than at the no-expense-spared Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum, built in 2013 to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the end of the Korean War.

It is more than a hundred metres from the entrance gate to the Victory Statue – it goes without saying that this is mammoth – flanked by captured US military hardware on one side (including the USS Pueblo, the only American commissioned vessel currently held captive anywhere in the world, having been seized for spying in a major Cold War incident in 1968) and North Korean army stuff on the other. Inside, an absorbing 20 minute video tells a tale of how the Americans invaded in 1950, then Kim Il Sung fought them off before a strategic retreat led to the peace treaty of 1953. The whole museum builds to a superb giant rotating drum with a 360 degree panorama of one great battle scene: a painting in the round, foregrounded with full-scale military mannequins and real tanks, overlaid with a dramatic sound and video performance. You then exit through the gift shop, though the gifts are largely restricted to the 50 volume complete works of Kim Il Sung, available in several languages.

There are two war cemeteries very much worth visiting. The one for the martyrs who fought America is in the north of the city right next to the road to the airport. The one for those who died fighting Japan, apparently including Kim Il Sung’s mother and brother, is out by the Kumsusan Mausoleum, near the zoo.

A Twenty-First Century Country

As well as a focus on the Kim cult and a story of audacious national survival in the face of imperialism, this tour goes into a lot of effort to show foreigners that the DPRK is not as poor or backward as you might think.

A perfect example is our visit to the catfish farm in the south of the city, though the result is not quite as intended. To get past the entry gate we need the permission of an armed soldier. We park near a huge mosaic of the two leaders, before whom we have to bow, as we are told the workers have to every single morning. Then we are shown two large rooms full of 40 or 50 virtually life-sized photographs of when Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un each visited the farm. We are even shown half-a-dozen stuffed catfish that are supposed to be the very ones that Kim Jong Il himself saw on that fateful day all those years ago. Beyond parody.

Then we are shown the “control room”, where two or three laptops are left switched on, purportedly monitoring the exact temperature of the water, the precise mix of the fish food, and the awesome productivity levels of recent months. Oddly, the laptops are not actually connected to the graphics we are then shown on the screen on the wall. In a couple of laboratories, where we are told various experiments are undertaken, the test tubes are still in their cellophane packaging and the notebooks displayed artfully on the desks have clearly never been used. Similarly, the workers’ social area – with canteen, sauna and games room – has not been touched. In fact, there is a surprising lack of workers about the place this Tuesday morning. Outside, we are told there are 42 large bays of catfish though we are shown only two. All very fishy etc.

Sadly, we did not go to the movie studio but we heard similar tales from those who did. (Nor did we manage to wangle our way into the Pyongyang Golf Club where Kim Jong Il famously got a world record round of 34 with 11 holes-in-one.) We did, however, go to the Kangso water bottling factory, possibly the only water bottling factory in the world where there was no running water in the bathrooms, and where we bought bottles that looked absolutely nothing like those we had been told were filled here.

Another example is the atom-shaped SciTech e-library and exhibition space on the east bank of the river. We are told there are 3,000 computers in the e-library, and certainly we saw a lot of monitors, keyboards and mice (if not actual computers) laid out on desks, though our attempts to turn one on were thwarted through lack of an “access card”. About twenty were being attended by local students, apparently gaining access to a local intranet though not the World Wide Web. Meanwhile, we were directed to take photos of a plaque that marked the seat in which Kim Jong Un sat when he attended the launch of SciTech in 2015.

In the exhibition space, there is an exact replica of a DPRK satellite. Then there are a series of rooms with science games for kids. All quite imaginative, except the lights and machines were all turned off as soon as we had seen them. The whole place reminded me of “speculative learning” in Swift’s Grand Academy of Lagado: “The only inconvenience is that none of these projects are yet brought to perfection, and in the meantime the whole country lies miserably waste, the houses in ruins, and the people without food or clothes.”

The streets of Pyongyang (“flat land”) have that imposing Stalinist scope, wide and immaculate (there is no litter, never mind graffiti). At first glance, at 30 mph, from a distance, the buildings look impressive: skyscrapers stand in clusters of similarly designed pastel-coloured comrades. But on closer inspection, the outsides need a lick of paint and it is not clear what if anything is going on inside some of them.

There is certainly nothing going on inside the pyramid-shaped Ryugyong Hotel. This is proudly pointed out as the tallest building in the country, though it is also admitted that it is not yet complete despite having been started in 1987. There is construction work across the city; maybe as many as 20% of the buildings have cranes at them, and work proceeds at some, even continuously in three 8-hour shifts. (Amusingly, we were told that workers prefer construction jobs at night because then the managers are not present.) We were allowed to walk down Future Scientists Street, the most colourful, most prestigious area of the city, which is supposed to be its shop window. Are these buildings full? Or is it all just for show? It’s hard to tell.

Fun & Games

As far as is known, there are 2.5 million people living in Pyongyang, 10% of the country’s total, which is half the number in South Korea. We saw some of them having very normal fun.

On Liberation Day, never more than a couple of paces from our tour guides, we joined lots of locals meandering around Moranbong Park, the city’s main lung, where people in their work units or housing units spread out their picnics and set up loudspeakers for folk music, karaoke and dancing. And we went to the circus, with synchronised swimmers along with jugglers, clowns and trapeze artists performing before 200 foreign tourists in the front-centre of the packed 2,000-seat auditorium.

One of the few places we were allowed to roam without our guards was at the Munsu Waterpark. We had two hours of relative freedom, mingling with hundreds of natives, messing about in the dozen or so swimming pools, inside and out, with water slides, diving boards and wave machines. An oasis of normality in a genuinely relaxed atmosphere (though two-piece bikinis are not used; this is 1953 don’t forget). We also swam in the ornate Olympic-sized swimming pool at the Changgwangwon Health Complex, where in addition you could have a sauna or choose from one of the eight or ten hairstyles that were on offer at the barbers.

A highlight was attending the first ever Pyongyang beer festival, which attracted quite a bit of media around the world as well as long queues for the 7pm opening every night throughout August. On the west bank of the Taedong near Kim Il Sung Square, there were kiosks and uniformed waitresses selling a handful of (rather good) local beers with cold meats to several hundred wealthier people in the area nicknamed Pyonghattan (geddit?). Chukbae! Whether it was just official big-wigs or perhaps a broader middle class, around here and across the water at the Ryugyong Leisure Complex – where there are bowling lanes and an upscale spa and gym – you can sometimes see an Audi, a Mercedes or even a Hyundai in the car park.

While millions of North Koreans go hungry, tourists are fed like royalty. There are no menus for foreigners; you eat what you are given. There are often six, eight or even ten delicious side dishes of soup, green bean pancake, pickled vegetable kimchi and rice. Specialities include very tasty cold noodles (buckwheat in a broth along with chili sauce and mustard), barbequed beef or duck, and of course dog (euphemistically called “sweetmeat soup”, it is considered a rare delicacy, tastes like mutton with chillies added to taste, and no, we were not told the breed). Every meal is accompanied by a bottle of water and a bottle of beer.

Rather than one open space, the restaurants are usually divided into small rooms so people eat in the confinement of their own groups. The best place we went for cold noodles is the landmark Okryu Restaurant by the Taedong. Another great place is the Rainbow River Boat. Opened last year, for my birthday we had a buffet of a dozen hot and a dozen cold dishes, with a service station that included a complete piglet.

The North Korean won is of course not a tradable currency and the only time we were allowed to have any – and this is a very recent development for foreigners – was in the Kwangbok Department Store. Everything else was either pre-paid in Beijing, or in hotel bars and shops we used dollars and euros. In the hotels they accepted a rate of about 1 euro to 100 won, but in the department store there was an official kiosk that exchanged 1 euro for 7,000 won. We were allowed only €5 worth each, but with that we had a great time buying confectionary, toiletries, two bottles of rice wine, and two top-notch watches.

Apart from the much-coveted beer festival T-shirt, common souvenirs found at the main sites included typical stainless steel chopsticks, ginseng tea and stamps. By far the best buys, however, are copies of classic agitprop posters. There are prints to be found at the Foreign Languages Bookshop, near Kim Il Sung Square, though excellent oil-on-canvas versions from the Mansudae Art Studio (where the originals are all created) are to be had at the small Wolhyang store near the Arch of Triumph (5m taller than that in Paris). We bought three for the princely sum of €70 each. When we asked if they would offer a discount for such a bulk sale, the shopkeeper simply did not understand the point we were making; the market economy is not here yet, even underground.

We did find some surprising Western influences though. In restaurants, we watched a dubbed Sherlock Holmes TV show and Tangled, the 2010 Hollywood movie about Rapunzel. We saw Winnie-the-Pooh dolls and even one or two – no more – Barcelona replica football shirts that had somehow been smuggled in.

Western tourists have been coming since the collapse of the Soviet Union forced the DPRK to look beyond its traditional sources of foreign money, and US citizens were allowed entry from 2002. Tourists who had been before told us they spotted some very first signs of liberalisation under Kim Jong Un. They said mobile phones are a bit more common, and clothing is a little less formal. But when I asked one of our guides whether the country had changed much in recent years, he just looked at me confused; he could not comprehend any notion of the country changing. It really is still 1953. We concluded that any sudden awakening is likely to invoke a shock to the system of individuals as well as of the state.

Despite these liberal baby-steps, Kim Jong Un is reported in the West to be regularly purging his officials and family as well as testing more nuclear missiles. Political scientists say the country is on a more or less permanent war footing, not because it actually wants war, but because the prospect of war staves off internal dissent and justifies the state’s poverty as necessary to maintain its massive military spending. It is existential, and contrary to perceptions in the Western media, from this perspective it is totally rational.

The state controls all aspects of people’s lives. It decides where they live, who they marry (it is not officially possible to have children outside wedlock) and where they work (six days a week, starting at 17 until 55 for women and 60 for men). One woman in her forties told us that twenty years ago, after her father was diagnosed with terminal cancer, he decided that she should marry before he died, primarily so his wife could live with his daughter and son-in-law. She was at university and in love with a fellow student. But her father would not allow that marriage because both were only children, which meant there may not be room in the house for two sets of in-laws. So the father found another man for her to marry. She was allowed to meet him for just five minutes before deciding whether to accept the arrangement. Technically, she could have said no, though the consequences would have been so dire the pressure to say yes was overwhelming. Now she has been married for twenty years and has a son and daughter, and when asked about her husband she just shrugged and said it was better for the country this way. But she had tears in her eyes as she told us this terrible story, crying for a lost love, a lost life.

Mount Myohyang

The rains come in July and are supposed to be over by August but this year it is hot (up to 35℃ in the day and 25℃ at night), and very, very humid. So it was good to get out of the sweaty city and drive north for an hour, with beautiful old mining villages and smoking chimney stacks lining each side of the river that we trace. In the countryside the ladies wear very cool long-peak tinted visors, whereas in the city they use colourful parasols. Generally, the DPRK appears surprisingly not very polluted: there are few cars and little industrialisation, but lots of green spaces – a particular feature are abundant lotus ponds – and heavy rains that clear the air.

We stopped at Pyongsong in the pleasant Jangjusan Hotel. Pyongsong is the ideal base to explore the verdant, rolling hills around Mount Myohyang (“mysterious fragrance”), the main attractions of which are close together a further hour and a half north.

The International Friendship Exhibition is unmissable. Surrounded by rural poverty are two huge buildings with oak doors and high ceilings: No1 is for Kim Il Sung, built in 1978, and No 2 is for Kim Jong Il, from 2013, and they contain what we are told are 110,000 gifts the leaders received, spread over 70,000 square metres of marble flooring. We saw only a few rooms and 500-odd gifts, though these were remarkable enough. Most were from predictable dictators like Assad, Gadaffi and Mugabe, Soviet-era Eastern European leaders, Russian and Chinese business and trade groups, and oddball national friendship societies, including the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Great Britain (Marxist-Leninist). The centrepiece is the crystal missile from China, sent to commemorate the launch of the DPRK H-bomb programme in 2013.

After this we started to feel the benefit of the length of our trip as we were clearly in places that very few tourists get to see. Here, there are simply no cars on the roads, which are more potholed, and pass over bridges more derelict, like in a war-zone; and the poverty is more extreme. Our guides were much more than usually agitated whenever we stopped, and tried to prevent us even making eye contact with locals. We stayed at the Chongchon Hotel in Hyangsan, really in the middle of nowhere. The lobby had obviously recently been re-painted but the veneer was thin. The bar and restaurant were shut. The electricity failed at about 7pm. And here I was even forbidden from running around the hotel car park (in case I saw the less renovated areas at the back). Yet the staff were incredibly friendly to us, as if they hadn’t seen enough foreigners to know about the need to hold the party line.

It is said that Kim Il Sung’s mother was a practising Christian so although religion is effectively banned two or three churches and the Pyohon Buddhist Temple, dating from 1042, have been allowed to remain open. We are told there are a handful of Buddhists living in the dozen or so buildings in the acacia, fir and maple forest of the Manpok Valley, where we spent a wonderful morning hiking up the steps and across the rope bridges over the waterfalls of the mountainside. The locals were evidently astonished to see foreigners here.

The Ryongmun Caves are unremarkable but for a fascinating accidental cultural insight. They run for 7km and are well lit. The local “expert” guide gave us no geological background at all. Instead, she took every opportunity to reinforce the party’s values – for instance, by showing us where Kim Il Sung had had his photo taken, near the Pool of the Anti-Imperialist People’s Struggle – and then kept pointing out stalactites that she thought looked like a dolphin or an eagle or whatever. When she found various different-sized erect penises and open vaginas, she was gigglingly desperate to tell us which she thought might look like ours. State control is clearly infantilising.

Mount Paektu

There are pictures of iconic Mount Paektu (“white head”) all over the country, but it is remote and hard to get to: right on the Chinese border in the far north and smothered in unpassable snow for much of the year. So we were very lucky to be on a rare chartered Russian Ilyushin flight to Samjiyon along with about 40 other foreigners.

At the airport everyone decants into separate buses with their respective tour guides to drive another hour north to the funicular railway station. Our guides told us this was not working so we drove on. Even when we saw some other buses offloading their passengers, who got into the carriages and trained it up the mountain-side, meeting us at the station at the top, our guides still insisted that it was not working.

It is another 1km walk to the very top of the 2750m peak, the highest in both Koreas. The volcano is a million years old and in its giant crater is the stunning Lake Chon. There is a cable car down the inside, though we are told this is not for use by foreigners. Mount Paektu has its own micro-climate and can get cold and cloudy very rapidly; it tends to be at its best in the early mornings.

On the outer slopes we see the famed Mount Paektu “marching squads”. These are groups from their work units or housing units, dressed in khaki like soldiers, who come here during the summer months to yomp around, team-building and enjoying the views.

We had signed up to run a half-marathon on the lower slopes, but at the last minute it was cancelled as too few people had applied to make it viable; the first one, last year, attracted 30 runners, but this year there were just four of us. No matter: there was a party of ten or so doing a cycling tour (there is also a kayaking tour) and they had a spare bike so I managed to blag it and joined them on a fabulous, easy descent for about 50km. (One of them had been raised in East Germany, giving an interesting perspective on the DPRK, which he reported was similar to what his parents had told him it was like at home in the 1950s.)

We got a close look at the border with China on the way down, before visiting the Secret Camp at the foot of the mountain. This is supposedly where Kim Jong Il was born while Kim Il Sung was fighting the Japanese, and therefore an important centre of the country’s creation myth.

There is no running water, not even cold, in the Begaebong Hotel just south of Mount Paektu, but it is worth staying over to see two amazing sights nearby.

The Samjiyon Grand Monument – at just under 20m the second tallest statue in the country – pinpoints the area where it is said that Kim Il Sung spent his first nights back in the country after returning from China in the 1930s. And about an hour east is the Musan battlefield – marked by a relatively titchy 10m statue – where we are told that in one day 300 Japanese were killed in exchange for a single Korean.

The DMZ & the Border

Driving south from Pyongyang we stopped at Sariwon farm in the middle of maize and rice fields. Even here we had to visit ornate marble halls commemorating the visits of Kim Jong Il and Kim Jong Un. They had three enormous rooms each, with upwards of 30 photos of 1m x 1.5m in each.

About 100km before the border it starts to feel like M*A*S*H country, heavily wooded rolling hills, the battle ground of the Korean War. Near the DMZ we stop in Kaesong, the capital of the ancient Koryo Dynasty. Here they had removed the statue of Kim Il Sung as they were re-landscaping the main square to make way for the addition of Kim Jong Il. This has been happening in towns all over the country for the past five years. In the two days we were there, we saw them totally rebuild the main roundabout.

At the traditional Kayagum Folk Hotel we were warned we had hot water for only an hour and had to sleep on the floor, but we were not ready for what happened after dinner when our guides had gone to bed. Having been repeatedly told there is no pop music in the DPRK, we were surprised when as many as forty locals set up a loudspeaker in the car park, ingeniously via a car battery, and danced to the first thing we’d heard that didn’t sound like it was written by Kim Il Sung; it sounded like Russian techno. So we joined in. They were hammered on beer and rice wine, including one guy in military fatigues who kept shouting in English, friendlily, that “Korea is a very strong country”. We had a great time and were given rousing applause as we left to get some sleep. It all felt very Footloose.

There is a coda to this anecdote. For lunch the next day we went to have a picnic at the nearby Pakyon Waterfall, where we found the same revellers with their speaker, still drinking and dancing. Some of them rushed over to us to encourage us to join in again, but this time our guides were present. A guard appeared with a megaphone, the music was turned off, and we were marched straight back to the minibus.

The Korean peninsula is of course of historic strategic importance, jammed between China, Russia and Japan, and we are close to the fulcrum of the crisis. Kaesong is 160km from Pyongyang and it is another 8km to the border at Panmunjom Truce Village, the home of the Joint Security Area, which is only 50km from Seoul. As we approach the De-Militarised Zone, a 2km strip of land either side of the 248km border, our guides again become extremely edgy.

After we march single file past the anti-tank barriers, the first stop in the DMZ is Armistice Talks Hall, which did what it says on the tin, and the next is where the peace treaty was signed. We note an unusual lack of photos on the walls here; then we learn that Kim Il Sung was not himself present at that time. Under the beady eye of very heavily militarised soldiers and watchtowers on all sides, we finally reach the Demarcation Line itself and have a great view of Freedom House on the South side from the consciously larger Reunification Pavilion a few metres away here in the North.

We did not go out to the east coast, though apparently there are good beaches there at Wonsan and at Mazon, roughly 4-5 hours from Pyongyang. We did, however, go to the west coast, where we visited the Sea Barrage at Nampo. But after 12 days we had a hankering for some kind of normality and personal freedom.

There are two ways out of the country. Either you can take the 23-hour train to Beijing which includes a 2-hour stop and full search at the border. Or you can get the flight out of Pyongyang, which we took, where there was a very light touch security search (our main crime was to hide a single note of local currency as a souvenir).

We felt exhausted, overwhelmed at the incident-per-hour ratio of experiences, full of mixed feelings like someone guilty at rubbernecking a horrific car crash. And yet we had had a great time.

24/10/2016 @ 10:19

Fascinating travelogue. I’ve been obsessed with NK for years. Read all the books you mentioned and more. My default stance has been not to go as my hard currency props up the regime but your trip notes and making me reconsider. Should go to dinner soon and you can tell us more

22/10/2016 @ 00:39

I found this article fascinating. Thank you for sharing your experiences.

21/10/2016 @ 21:51

A lot of inaccuracies in this

1) why would your computer not work? The internet doesn’t work on it, which is not the same. Just say there is no internet coverage.

2) they don’t delete files at the airport, they do a very cursory check

3) going with a tour company is not the only way of going – you can go on a work visit eg to embassies, UN, etc.

19/10/2016 @ 00:53

I loved the pic of Freedom House from the NK side. I was there in 2005 and took the tour from Seoul. It was interesting to see the House from the backside. Brought back a lot of good memories.

18/10/2016 @ 05:42

Foreign visitors of North Korea cannot see what resident foreigners can see. Here’s a glimpse behind the veil: http://northkoreacapitalist.tumblr.com/post/86201882467/north-korea-behind-the-veil-visiting-foreigners

17/10/2016 @ 08:04

Interesting experience! I’ve always wondered about the “DPRK touring experience”, now I know.

17/10/2016 @ 07:15

The account is really good, not impartial but ok, to be expected.

The main inaccuracy is when you talk about the non existent “Peace treaty” of 1953, there has never been any kind of peace treaty, it was an armistice what was signed in 1953.

17/10/2016 @ 02:35

What a horrible country. I feel bad for those people who have no idea of what life is like outside of NK.

I would never visit NK because I would never bow down like they force you to.

20/10/2016 @ 21:33

Or stand for the pledge of alliegence.

16/10/2016 @ 17:34

It seems we were there on the same week Simon. Here’s a video I made of the trip incase interested: https://youtu.be/pwtpTGB5vHQ

16/10/2016 @ 15:33

Very interesting and entertaining article. Thank you for sharing.

16/10/2016 @ 05:53

Great article!

14/10/2016 @ 16:05

Very interesting read…1984 meets the Truman Show indeed!

04/10/2016 @ 22:00

Great account. Always wanted to go, but now don’t need to.