Surprisingly few foreign tourists make it to Punjab, the small state on the north-west of India neighbouring Pakistan. But those who do witness two very different treasures – the Golden Temple of Amritsar and the border ceremony at Wagah – that are among the greatest attractions in the world, never mind the sub-continent.

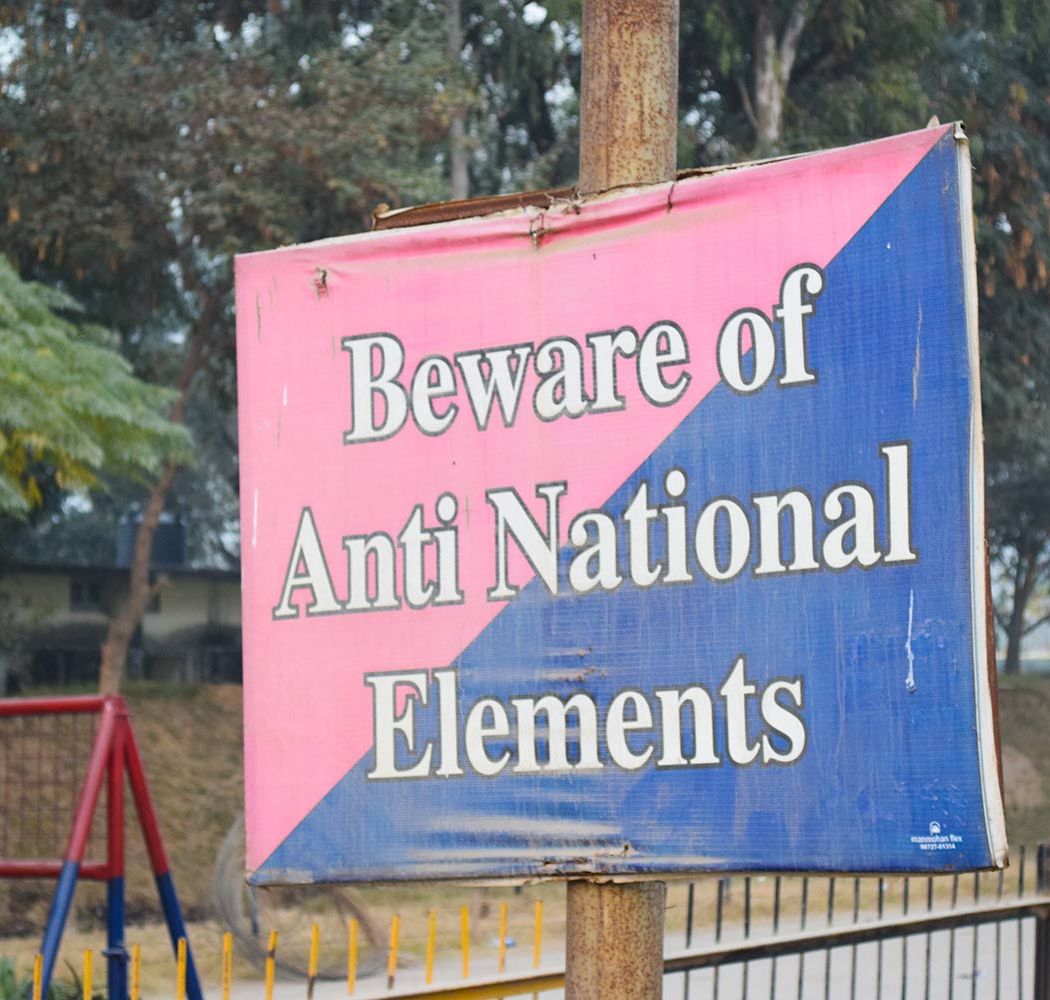

Although there are constant reports of army blockades, political protests and terrorist activity throughout the region, you will be safe in the city and at the heavily guarded border, which are the places you want to go. You should of course monitor the latest Foreign Office Travel Advice, though there are currently no restrictions at all and lots of flights that take just an hour from Delhi.

To me at least the very word Amritsar has always conjured images of exotica. Yet there is a contemporary feel to the city, where service standards seem a bit sharper than in much of India. Disappointingly, there is also a modern heavy smog all around.

Amritsar is the capital of Punjab, and Punjab is the ancient home of Sikhs. Just under 60% of the 30 million people here are Sikh; almost all the others are Hindu. This is the best place in the world to find tall, straight-backed, dignified men in turbans with magnificent moustaches.

I stayed at the Hyatt, 20 minutes from the old city. The most famous Punjabi restaurant is the Brothers’ Dhaba at Hall Bazaar, where local specialities include Sarso Ka Saag with Makki Ki Roti. And the most celebrated Punjabi delicacies are from Bansal Sweets on Lawrence Road.

Obviously, the principal reason for coming here is the legendary Golden Temple of Amritsar, the Harmandir Sahib (“the abode of God”), the holiest Sikh gurdwara (“the gateway to the guru”), and undoubtedly one of the most spectacular monuments on the planet. The city was founded in 1574 by the fourth guru, Ram Das, and the shrine was completed in 1604 by the fifth guru, Arjan. It was rebuilt in 1764 and the upper floors were covered in its distinctive gold plate in the early nineteenth century to commemorate the securing of Punjab’s borders.

Inside the main gate it feels like entering a mini-city, a vast complex of buildings with as many as 100,000 people every day coming to worship. Thousands are happily milling about, lolling in every cranny, praying in every nook, eating the free meal that is available at every gurdwara.

You take one of the free orange head-scarves to cover up (no bare arms or legs are permitted either) and leave your shoes at the large and efficient collection point. After wading through the warm foot bath you mostly walk on thick carpet over the cold marble floors. A calming religious music is piped all around, preparing you for your first, awesome view of the Golden Temple itself.

Stepping through one of the four entrance gates I could see that the holy lake is several hundred metres square, with large white buildings all around the perimeter. Day and night devotees bathe on the steps at the edge of the freezing water, surrounded by massive goldfish.

In the centre of the lake, beautifully reflected in the water, stands the temple, looking slightly smaller but even more immaculate than I had expected. It is reached by a long causeway at one end; the queue takes about an hour an half but that just gives you a chance to catch your breath in time to witness the singing and praying within. Adi Granth, the holy scripture of Sikhism, was installed in the temple from the start and there is a ceremony every morning when this book is placed inside the gurdwara and again in the evening when it is removed for Sukhasan, meaning relaxation. After edging past the holy book, head up two floors to take in the view from the top.

The other notable building is the Akal Takht Sahib, just behind the start of the queue to the causeway. This was rebuilt in 1999 having been damaged in 1984 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ordered the Indian Army to attack the Golden Temple to oust the occupying Sikh separatist movement of Dharam Yudh Morcha. Sikhs were outraged at this desecration and within six months Indira Gandhi’s Sikh bodyguards murdered her for her sacrilege.

There is a very relaxed and welcoming vibe around the complex. The whole time I was there – all day and back again in the evening – I saw just a handful of non-Indian faces. Which meant that while I was walking around the lake I was repeatedly asked by locals to have a selfie with them on their mobile phones. Although it was great fun, on one occasion a guard put a stop to it, apologising for any hassle. “They are from the backwaters and don’t see many foreigners,” he said.

One of the most brutal scenes of the British Raj’s slow fall occurred in Amritsar, just a five minute walk from the Golden Temple. On 13 April 1919 a crowd of non-violent protestors and pilgrims gathered on the field of Jallianwala Bagh as part of the growing campaign for independence. The British Indian Army, commanded by Colonel Reginald Dyer, entered through the main gate; fifty Gurkha riflemen were ordered to open fire repeatedly for a full ten minutes. As the field was surrounded by walls, there was nowhere to hide. It is estimated that more than 1,000 were killed and a further 1,500 injured in the massacre.

The memorial at Jallianwala Bagh is far from solemn and a great place to take a breather from the hectic bazaars all around.

Punjab was utterly transformed by the independence of India and the birth of Pakistan in 1947. Up to ten million people were displaced, as Muslims left to cross the border west, with Hindus and Sikhs pouring east, each to find sanctuary in their new home nations from the civil war that killed more than a million people.

The impact of this violence and migration has of course been widely documented. For visitors trying to understand this crucial heritage, I would strongly recommend Khushwant Singh’s classic novel Train to Pakistan, which tells the tale of the wider context through its effect on the India-Pakistan frontier village of Mano Majra.

The border lies roughly equidistant between Lahore in Pakistan and Amritsar in India, at Wagah, about 30km from each. These days, it is open throughout the day, after the gate is unlocked each morning and then closed every evening. It is the corresponding raising and lowering of the flags of both countries, accompanied by an extraordinary, co-ordinated ceremony, that brings visitors to this remote place.

There are touts all over Amritsar keen to take you out to the border, past rows of army barracks, lines of tanks and the occasional road checkpoint. There is a car park about 1km from the border where your driver will meet you afterwards to take you back. You walk through the two sets of police body searches and join a massive scrum where soldiers randomly blow their whistles and locals get the Indian flag painted onto their cheeks.

You need to get there in good time for the ceremony to get a decent seat. Your passport will get you into the small section for foreign tourists – I went on New Year’s Day and counted about fifty though I am assured that it is just the same seven days a week – but it is better to worm your way into the VIP stand right in the middle.

The road at the border is about 150 metres long, split in half by the border gate. There is raked sports stadium-style seating along both sides of the road on both sides of the gate. On the Indian side, there is a blizzard of colour and noise with as many as 4,000 people in the stands and spilling onto the road singing, dancing and waving national flags. Hundreds more are unable to get in so watch on huge TV screens outside. Typical of India, it all feels a bit like an abandoned building site and the arch welcoming people to the country, with a picture of Gandhi on top, is falling down. On the Pakistan side, there is a more sombre tone, not least because the women are all segregated on the right with the men looking grey on the left. But the impressive entrance edifice is a robust concrete tower.

A dozen or so of the tallest soldiers that each country can muster are then paraded on the road on each side of the border, to an ecstatic reception from everyone. They all wear similar flamboyant hats and garb, green and red on the Indian side, blue on the Pakistani.

Rival music blares over PA systems. On the Indian side an MC in white whips up the enthusiasm of the crowd by shouting into a mic and gesticulating angrily towards the border. The atmosphere quickly bubbles up as if it were the deciding over in an India-Pakistan test match.

Then the action begins. One soldier on each side screams into a microphone for as long as possible, each trying to hold a single note for longer than their enemy. This is the signal for pairs of their colleagues to march down the road towards the border gate in the manner of a John Cleese silly walk, egged on by the MC and shouting crowds. It is part camp pantomime but part genuine hatred, and the whole thing seems to be taken very seriously. This display lasts half an hour until the national flags are lowered at the border gate, which is the moment I remembered that these are both nuclear powers.

When it is all over, those locked out are allowed in and those in the stands heave on to the road to get photos of themselves with their team’s border soldiers.

All in all, this is an extraordinary spectacle which alone makes Punjab worth the visit. Coupled with the Golden Temple, it is a must-see destination.