A decade since the end of its twenty-six year bloody civil war, Sri Lanka faces a defining moment: the prospect of a nation at peace, with rocket-fuelled economic growth, in large part funded by China, is tantalisingly close; yet it may still be lost, caught in the terrible crossfire of global Islamist terrorism. While the future for this beautiful land is very uncertain, the attractions for adventure travellers are manifold and should not be ignored because of recent troubles.

The beaten track runs from Colombo in the west straight down past the fort at Galle and along the south coast to watch blue whales at Mirissa and loaf on the beaches around Tangalle that feature in all the brochures targeted at honeymooners.

Another heavily trodden path is through the hilly interior, where tourists retreat from the searing coastal heat and get a bit of culture, especially in Kandy, the centre of Buddhism. The itinerary also includes elephants in the Uda Walawe National Park, tea plantations at Haputale and Ella, as well as hiking on Horton Plains. Then there are the ruins of the ancient cities of Anuradhapura and Polonnaruwa, and heady stairs up the rock face at Sigiriya for stunning panoramas all around.

It is the lure of these routes that since the fighting stopped in 2009 has attracted many to what they see as “India light”, a first step for those who want to experience something a bit more “exotic”. You can easily get a visa at the airport, everyone speaks English, they use British power sockets and drive on the left, there are lots of ATMs and credit cards are widely accepted, the ubiquitous rice-and-curry isn’t too spicy, and it’s all relatively clean. There were barely 500,000 foreign visitors ten years ago; they had soared to 2.5 million in 2018. Sri Lanka was even Lonely Planet’s top country to go to in 2019. But of course this very popularity made these areas feel rather mainstream and unexotic, with the crowds thickest over Christmas and New Year, the middle of a season that runs from October to March, when the trains and hotels are booked long in advance.

Whether such numbers continue to come after the 2019 Easter Sunday bombings, when at least 250 people lost their lives in and around Colombo as well as in Negombo just north of the capital and in Batticaloa in the east of the country, remains to be seen. The immediate foreign travel advice from governments in Britain and elsewhere was to avoid going to Sri Lanka at all. We happened to be there that weekend so have first-hand evidence of the shock and fear that swept the nation. But time will pass and for those who do come things will settle into a new normal.

In the long term, in any case, it is the roads less travelled for years – the remote north (the cultural home of the Tamils and the sites of the civil war) and the secluded east (with its quiet golden beaches) – that hold the greatest appeal for the adventurous. The weather is best in these parts between April and September, when the south and the west are muted anyway thanks to the rains.

Colombo: A Melting Pot

Traditionally, many tourists used Colombo merely to enter and exit the country, hardly stopping to look around. That is a mistake and prior to the 2019 bombings at least it was all set to change as the city self-consciously began building business facilities along with tourist attractions to rival any in South Asia. In the five years since we were last here, Colombo had been transformed.

At the northern tip is a vast area currently hidden behind corrugated iron barriers. This is the planned “International Financial City”, or “Port City” as it is widely known. One of the most controversial of President Xi Jinping’s Belt & Road Initiatives, $2 billion of Chinese money is slated for investment here, sparking fears that Sri Lanka will be debt dependent on a foreign power for years to come. Almost 3 square kilometres of land is being reclaimed from the Indian Ocean, on which the blueprint is to build what will feel like a brand new city of skyscrapers akin to Dubai or Singapore bolted on to Colombo as we know it now. Posters all along the fencing give a feel for what it could be like.

Nearby, every five-star global hotel chain you have ever heard of has a huge building under construction, and there are new iconic sites, including the Lotus Tower that is due to open in 2020 and is already visible on the skyline from across the city, along with upcoming international shopping malls. The brave idea is to attract new wealthy people to pump up the local economy; whether that survives the aftershocks of 2019 time will tell and it will be fascinating to see how China responds to the very real threat posed to its interests from international terrorism.

In the meantime, the obvious place to stay is the landmark colonial Galle Face Hotel, a little south of the IFC at the end of Galle Face Green, usually a patch of brown grass in fact, by the coast, a haven for kite fliers but less of a magnet to beach lovers. The hotel has a lovely courtyard for a local Lion beer (though not on the full moon or over 13-14 April, the Sinhalese and Tamil New Year, when the whole country is dry to prevent too much partying) and a cigar (though not bought in duty free as it is illegal to bring any tobacco products into Sri Lanka).

The Cinnamon Grand, the Kingsbury and the Shangri-La were of course all bombed (and there was a small explosion, probably by accident, at the Tropic Inn too). For somewhere more niche, try the former prime minister’s gorgeous residence, Tintagel, scene of a famous assassination in the 1950s, in the elegant district of Cinnamon Gardens; or the faded glamour of the Grand Oriental Hotel, which has a lovely view across the port from its old world piano bar; or the modern Marino Beach Hotel with its fabulous infinity pool facing the ocean.

A very popular place to eat is the Ministry of Crab, owned by local cricketing legends Mahela Jayawardene and Kumar Sangakkara, which is often cited in lists of the best restaurants in Asia and the world. There is also a cool underbelly to Colombo and a good place to find it is in Baillie Street Merchants.

Not far from the IFC are the Fort and Pettah districts, split by the thin line of water between Lake Beira and the port on the open sea. These may soon amount to what is sure to be marketed as the “old city” with a historic lighthouse and clock tower and meandering street markets. Not far from here is St Anthony’s Shrine, a Catholic church where almost 100 people lost their lives on that Easter Sunday, as well as the striking red and white striped Jami-Ul-Alfar Mosque.

Of Sri Lanka’s 22 million people, 7% are Christian and 10% Muslim, mainly Sunni. Christians have historically played a bonding role here, as the congregation includes both Sinhalese and Tamils, so it was particularly unexpected that this community should be targeted. It seems that a local terror group, the National Thawheed Jammath, probably with support from international Islamist organisations, exploited Sri Lanka’s determination to have very low key security measures in its misguided attempt to show the world there was no longer a threat to peace because the civil war was over.

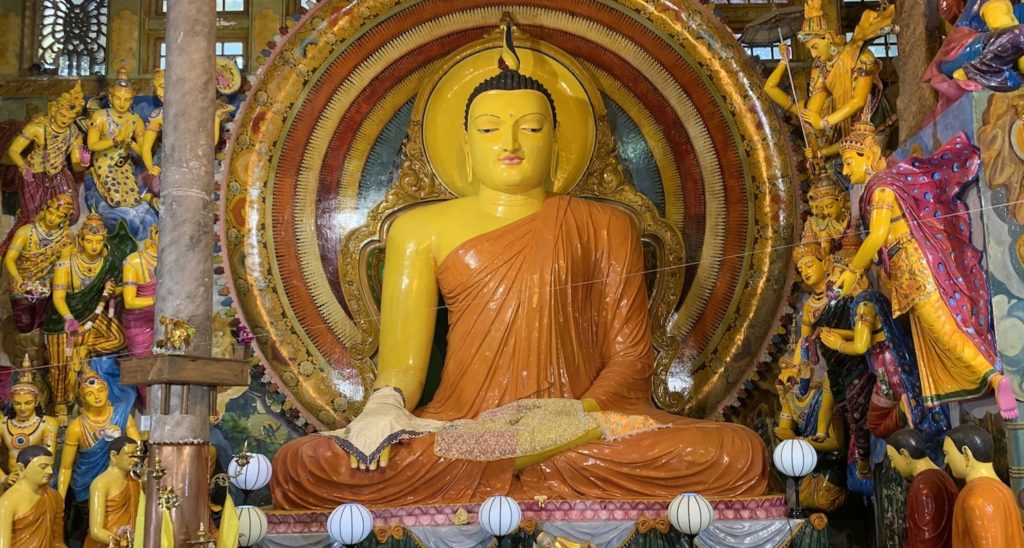

Some 70% of Sri Lankans, mostly Sinhalese, are Buddhists. One of their most important and most visited temples is Gangaramaya, near Lake Beira. For many years, an elephant was controversially chained to its courtyard, but these days it seems to have gone. Their most cute and most photogenic temple is Seema Malakaya, just around the corner, actually floating on the water. Remember: no selfies here as it is rude to turn your back on Buddha. About 13% are Hindus, a religion originally brought from Tamil Nadu in south India in the tenth century when migrants settled in north Sri Lanka just 50km across Palk Strait.

Another serene location is Independence Square, south-east of Lake Beira, which has a contemplative Memorial Hall at its centre, next to a statue of Don Stephen Senanayake, the first prime minister and “father of the nation”.

It is very easy to get around Colombo and 500 rupees or €2.5 will be enough for almost any tuk-tuk ride. But if you want to visit the longest named capital city in the world – Sri Jayawardenapura Kotte – which is basically an eastern suburb of Colombo, you will need a taxi as it is a bit further out.

Fort Railway Station is exactly how you hope it would be: hot, noisy, smelly, and colourfully and chaotically busy. These days it is watched over by the new pink and green Lotus Tower. Trains normally have three classes and you are going to want the only one with A/C. The problem is that they can be sold out months in advance and you can’t reserve online. So unless you’re here for a very long time, your best bet is to walk a few metres from the ticket office to the Railway Tourist Information Service where with a bit of charm foreigners can negotiate a package that is likely to include a car/driver at some point as well as a train ticket. For what should have been a €10 seat you might pay ten times over the odds; but at least you’ll have a place on the train.

We booked the 5.5 hour intercity to Jaffna in the north then a driver to Trincomalee in the east and another driver back to Colombo. There is an overnight sleeper, with no beds, and a slow day train too. Modernity means carriages are no longer so packed that passengers are sitting on the roof or standing precariously on running boards while clinging for dear life to the outsides; but even the intercity is a traditional bone-shaker and just like in the movies the carriage doors all remain wide open for natural ventilation.

Jaffna: The Cultural Home of the Tamils

The Portuguese arrived in 1505, the Dutch in 1602 and the British in 1796. Ceylon metamorphosed into Sri Lanka when the whole sub-continent shook off colonial shackles in 1948. However, nationalists in the majority community were quick to promote the Sinhala language and the Buddhist religion, arguing that under British rule minority Tamil-speaking Hindu-worshippers in the north had become over-represented at the top of society. As tensions grew, repressive state-of-emergency conditions in Tamil areas after 1971 triggered the emergence of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam as a leading advocate for an independent Tamil state.

When in 1981 Sinhalese rioters burned down Jaffna library – a symbolic attack on education and culture in the de facto Tamil capital – the touchpaper was lit that flared into a gruesome civil war two years later which was to last almost three decades, claiming the lives of more than 100,000 Sri Lankans. It is widely acknowledged that there were atrocities on both sides, with suicide bombings, kidnappings, rapes and executions, political assassinations and endless broken ceasefires. These wasted years of fear and death, economic collapse and government paralysis were then capped by the Asian Tsunami on Boxing Day 2004 when another 30,000 people died and thousands more were left injured or homeless. No wonder visitor numbers were low.

In the end, the Tamil Tigers were whittled away and defeated. Yet even now, almost ten years to the day since the violence ended, there are still very few tourists up here; we counted no more than a handful over four days. There were clusters of soldiers to be found at controversial war monuments, and we often stopped to ask them the way, but the military presence was very light touch and we were free to wander more or less wherever we liked.

The city of Jaffna is the bosom of the Tamils and very different from the rest of the island. Most obviously, they speak a different language and worship different gods. They seem to like more of everything here: the words are even longer, perhaps to accommodate all 247 characters in the Tamil alphabet compared to the already substantial 58 characters in Sinhalese, and of course there are 33 million gods of Hinduism against the one Buddha.

The food is different too. The mango is the symbol of the region and Mangos vegetarian restaurant in Nallur with its atmospheric open-air kitchen is unmissable for a thali lunch or a dosa dinner along with a creamy lassi; as long as you don’t mind waiting as the service is very slow thanks to its enormous popularity. Another essential is the defiantly authentic Malayan Cafe near the colourful fruit stands in town: there’s no menu, just point at food near the counter; there’re no plates either, just banana leaves smothered with spicy sauces; delicious and filling for 10 rupees.

The place to sleep is Jetwing Jaffna by the leading high-end boutique brand on the island. They have a lovely roof-top bar for sundowners and their excellent restaurant serves the versatile hopper as a dosa or like stringy noodles for breakfast.

Nallur, now a north-east suburb of the city, was once the capital of the ancient kingdom of Jaffna and close together along Point Pedro Road are the rather disappointing only remaining pointers to this empire: the rotting Mantri Manai palace, the modest Sankili Thoppu arch, and the golden statue of Sankili II, the last king, who was overthrown by imperialists in 1619.

Nearby is the Nallur Kandaswamy Kovil. This is an ornate Hindu temple where the usual demands for a modest dress code are thrown over as men are required to remove their shirts as well as their shoes before entering.

The dominant feature of Jaffna proper is the seventeenth century Portuguese-cum-Dutch fort. Back towards town is the grand white library, re-built on the site of that burned down in 1981. And on out to sea is the Pannai Causeway that connects the peninsula to a cluster of beautiful islands just off the coast, where much of the fiercest fighting in the civil war took place.

The best way to get around them is by hired scooter (there are rental places all over town) because most are linked by long, thin bridges. The roads are mostly good but you’ll feel like the only one on them apart from the occasional tractor.

There is an obvious clockwise loop that can be done in a day, starting with Mandaitivu (for bird-watching), then moving on to Velanai (on which the main town of the region, Katys, and the beach at Casuarina are both very pretty).

Next is Pungudutivu, where you need to leave your moped at the dockside while you catch a rickety ferry for just 20 minutes across to Nainativu to see the north’s only major place of pilgrimage for Buddhists and its most important Hindu temple. There is either a death-trap boat – bulging with pilgrims, including women carrying young children who cling to their colourful saris, sitting and standing around the open engine in a cramped hold below deck – of the kind you see on the news when they sink; or the self-described “semi-luxury service” which is bigger and faster and just has to be safer. We took one out and the other back.

One boat docks in front of the Buddhist site, Nagadeepa Purana Vihara, and the other a ten minute walk along the shore by the Hindu temple, Nainativu Nagapooshani Amman, with a large sandy courtyard and lots of colourful cartoon effigies where again men have to remove their upper garments to get in.

From here you have to double back through Pungudutivu and Velanai to get to Kerainagar via the short ferry that will carry your scooter with you. The last boat leaves at 6pm but if you miss it, as we did, you can always offer the pilot a few rupees to do a special trip, which then means it’s also fun riding the last 20km back to Jaffna in the dark.

You will see plenty of damaged buildings, but all monuments to the LTTE have been destroyed by the government. There is just one memorial in the area, to ten government soldiers killed in an attack by the Tigers, on a dusty track just north of the AB road on Velanai. It is policed by soldiers to prevent vandalism. This trail used to run to Jaffna but it has not been repaired since an explosion in 1993 so you have to turn back.

The real purpose of coming here is to enjoy zooming around the causeways over seas afloat with fishing boats. The water is often not much more than a metre deep, full of fisherman wading waist-high to attend to their nets and traps, so the sun bounces back from the sandy bottom to create a stunningly atmospheric light. On the islands, the deserted roads are all lined with forests of coconut and palmyra palms splayed on thin stalks like giant dandelions before you blow the tops off.

It requires a second day to get to the most outlying island: Neduntivu, usually known by its Dutch name, Delft. The ferry to Delft leaves from the same pier on Pungudutivu as that to Nainativu. This one, run by the military navy, is free and rusty and flaking paint and crowded of course. It leaves at 8 and 9 each morning, takes an hour, and returns at 2.30 and 3.30 in the afternoon.

You will easily pick up a waiting tuk-tuk on the jetty for a tour of the island after a papaya juice from the only hotel, the Delft Samudra Hotel & Restaurant. This is a coral island, and coral has been used to build arrow-straight solid walls like dry stone to divide the land, which is dustily hot and zigzagged by dirt roads. There are stringy banyan trees and a massive baobab planted in the sixteenth century. Around 500 wild Portuguese horses run free, but the stars of the show are the thousands of flamingos just off the south coast, their pink wings tipped underneath with black becoming as visible as their white bodies only when they take flight.

The Route Through the Civil War

To get a better feel for the realities of the civil war, you need to take the main road from Jaffna along the north-east coast of the mainland, heading towards some of the most tranquil beaches in Asia. It is here that the fighting ended, following a sustained military assault by the Sri Lankan army against LTTE guerrillas who were effectively using local Tamils as human shields. The road is new, part of government investment in the area in the past few years, and runs through green fields, where you will see dozens of wild peacocks, and past lovely golden beaches. In this beautiful setting, there are several easily accessible sites from the awful conflict.

The first that you come to is at Elephant’s Pass, a 1km causeway near the coast, that served as the border between north and south. Typical of the government’s attempts not only to annihilate but also to humiliate the LTTE, the huge Victory Memorial was built here in January 2009 as soon as the causeway reopened but while the fighting still had four months to rage. It glorifies “the steadfast political leadership, unshaken as a mountain, which brought an end to the era of terror”.

At the other end of the causeway is another memorial, this time honouring a suicide soldier who reputedly single-handedly stopped a Tigers’ bulldozer loaded with explosives that was headed towards government forces.

Slightly inland, you can skip Killnochchi as the iconic fallen water tower that was there has now been cleared and head straight for Puthukkudiyiruppu to see for yourself the massive memorial that has been erected on a platform at the end of a footbridge in the middle of a lake. Assertively named “Conquest”, it was built within six months of the war ending.

The war began on 23 July 1983 and ended on 18 May 2009 at Mullaittivu, where the A35 turns into the A34 road between a lagoon and the ocean. Here, an estimated 100,000 Tamil civilians had become trapped in rebel territory and suffered shelling from government forces before they were freed to cross the causeway that still has soldiers hiding in sandbagged dugouts at the south end. When LTTE leader Vellupillai Prabhakaran was killed on a neighbouring beach, the government was able to announce that the Sri Lankan lions had finally wiped out the Tamil Tigers.

There was no peace settlement, little active community reconciliation, and since then a concerted attempt at government imposed forgetfulness. War graves and statues commemorating the LTTE have been removed; these symbols of government victory are all that there is. One can only hope that the Tamil people are allowed to hold their dignity and their place in the nation in the face of some efficient mythologising by the government that is visible in the sites along this route.

Beautiful golden beaches, lapped gently by the blue sea, run for miles along here without a single hotel in sight. There is just an army welfare cafe, which serves a decent lunch. With no airport in the north, and tourists apprehensive or ignorant about what they might find in the former battlefields, few came here even before the 2019 bombings. Yet this is not only a place to get insight into Tamil culture and to understand the horrors of the civil war, it is also a paradise waiting to happen.

The Quiet Golden Beaches of the East

It is 230km from Jaffna to the east coast hub of Trincomalee, which the LTTE hoped to include in a separatist Tamil state. There are tiny fishing villages, empty beaches and occasional lagoons all the way along the peaceful shoreline. This does have an airport – Cinnamon Air fly here in cute planes – so there are more tourists and facilities than in the north, though nowhere near as many as the major routes of the west and the south.

Just above Trinco, as it is known, is Pigeon Island, popular for snorkelling, and a small reef for basic scuba diving. There is also whale-watching and fishing in the sea and the lagoon. But the real attractions are the golden beaches. The first you come to is the long straight line of Nilaveli, then the curve of the bay at Uppuveli all the way into town. Both are currently at about the perfect level of development: unspoiled but with enough facilities to make it fun and easy for travellers. There is a sprinkling of bars and restaurants and guest houses as well as diving centres, all of which are heavily advertised on billboards along the road, set back some way from the coast. There are loads of colourful fishing boats pulled onto the sand, and there is also an ATM.

The best places to stay are not far from the lagoon that splits Nilaveli from Uppuveli where it empties into the sea. Trinco Blu By Cinnamon is the biggest, flanked on either side by the Anantamaa Hotel and the USAID-funded Amaranthé Bay Hotel.

In Trinco town, a narrow peninsula juts into the sea, at the end of which sits the seventeenth century Fort Frederick. This is still partly used today by the Sri Lankan military, and is also home to an important Hindu temple, Kandasamy Kovil, that has a huge statue of Shiva.

There are two further stops on the east coast. It is another 130km down to Batticaloa, where 27 people were killed and more than 300 injured when a suicide bomber detonated an explosive in the courtyard of the Protestant Zion Church on Easter Sunday in 2019. Batticaloa is an historic and mostly Hindu town set between the sea and a swirl of lagoons. The main places of interest are the Dutch fort on the island of Puliyanthivu, and the beaches of Kallady to the east. Heading towards the busier south another 120km brings you to the last key stop on the east coast, Arugam Bay, where for six months of the year the tiny town gets overrun by surfers.