Uganda may not be as popular as Kenya or Tanzania for a basic Big Five safari, but it is more accessible than Rwanda and obviously the Democratic Republic of Congo to meet the gorillas, one of the truly great experiences in nature.

The Pearl Of Africa – a sobriquet you will see everywhere, originally coined by Winston Churchill in 1907 – has lots of additional natural wonders that make it one of the most impactful destinations in the sub-Sahara. It has the source of the White Nile; Lake Victoria; white-water rafting; the equatorial line; the world’s most powerful waterfall; the coveted handful of buffaloes, elephants, lions, leopards and rhinos; hippos and crocs galore; close-ups with chimpanzees; baboons and warthogs lining what feels like every road; and numerous rare and important bird species.

All of that is viewed against a backdrop of a dramatic human story: the gradual recovery from political tragedy, economic disaster and ecological catastrophe in the 70s and 80s. Here is a place to try to understand modern East Africa, from the increasingly cool urban vibe of Kampala to the fate of the pygmy people displaced from the forest to protect the gorillas.

Safaris are difficult for independent travellers because of the need to book in advance for guides and trucks, park permits, and lodges, usually with full board. But these tours are modular, and as there are far too many places to visit in one go the aim of this review is to give some colour about the main safari stops and some insights into where else to go beyond the forest, to help you build your own trip.

There are lots of safari operators, and some are specialists, such as in birding, but most seem much of a muchness and then it is down to the luck of the draw with the personality of your guide. We went with a highly recommended boutique, Livingstone African Safaris, with a great guide and a classic safari truck for just the two of us. The truck had a radio cassette player in what may be the perfect metonym for how little, apart from the widespread use of mobile phones, much of sub-Saharan Africa has changed in the thirty years I have been coming here.

Of all the traditional kingdoms in East Africa, the largest was Buganda, which in the thirteenth century was unified across the south of what is now Uganda, including Kampala. Although it was at its most powerful in the eighteenth- and nineteenth centuries, it could not prevent Britain from establishing the Protectorate of Uganda (the Swahili term for Buganda) on its territory, and adding northern regions, in 1894, as part of the imperial Scramble For Africa. Unlike in the colony of Kenya next door, a degree of self-rule was retained which has created uniquely Ugandan political and social characteristics. Today, there are more than 10 million Bugandans, who speak Luganda, comprising almost a quarter of the population of Uganda.

The Winds Of Change blew through Uganda in 1962 when independence was declared and Milton Obote was elected first prime minister with Idi Amin as commander of the army. Obote was deposed by a military coup in 1971 that led to Amin’s eight-year reign of terror, during which The Last King Of Scotland claims more than 300,000 people were killed. That horror ended only with the invasion of Tanzania. Obote returned to power in 1980 and committed atrocities against both the supporters of Amin and the anti-Amin National Resistance Army led by Yoweri Museveni. In addition, these “bush wars” were a time of exceptional devastation for the forests and their wildlife. Obote was finally overthrown and Museveni elected president in 1986, and he remains in power to this day, currently in his sixth unbroken term.

After a series of regional civil wars that lasted until 1994, largely in the north and east away from tourist centres, most infamously led by Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army, and despite occasional border skirmishes with the DRC and a terrorist attack by Somalia-based Al Shabaab in 2010, today Uganda is finally at peace. In the context of the region, Museveni’s rule is viewed as cautiously progressive, taking steps to end the human rights abuses, protect the wildlife, and stabilise the economy. However, on top of allegations of electoral fraud, the major blot is gay rights, as homosexuality remains criminalised with heavy penalties; even while we were in the country, SMUG (Sexual Minorities Uganda), an umbrella of NGOs, was shut down.

Serious problems remain, of course. The population is exploding: more than half of people are under 15, over a million refugees have fled neighbouring countries to settle here, and half the population is in poverty, driven by youth unemployment running at two-thirds. There is still corruption too, and though tourists are unlikely to be affected, petty bribes necessary for traffic police, for instance, are a daily hazard for locals.

Climate change, bringing more extreme weather patterns including floods and droughts but overall lower water levels, is having a negative impact on humans and wildlife alike. It has been noticed that some animals have even had to change their diets, for example hippos sometimes abandoning the search for grass and eating papyrus that is not so suitable for them. In general, the long rains still come in April/May and the short rains in October/November, though you may get a quick tropical soaking at any time.

Covid-19 has had a devastating effect too. Although there were few cases, and fewer than 4,000 deaths, the country, all its tourist infrastructure and all its schools, was effectively closed for two years, and it will take longer here than in developed economies to recover the lost earnings and learnings.

There are many excellent lodges in spectacular locations. Many have wild animals wandering about their grounds: herds of nervous kob antelope (the national animal, embedded in the country’s coat-of-arms) graze, sounders of kneeling warthogs mow the lawns, and bloats of hippos wobble through in the mornings and evenings to and from overnight pastures, usually necessitating armed escort to and from your cabins in the dark.

In fact, you quickly become familiar with guns. Almost every hotel, restaurant and place of interest is guarded by uniformed officers with pump-action shotguns, and your guides will usually be accompanied by one or two men in khaki packing AK47s. You will also adjust to the fact that you are a vital source of income for locals, so prepare for everything from meals and taxis to transport and safaris to cost more than you would anticipate. Of course, it is much harder to get used to the scenes of poverty.

Many people, in rural areas in particular, do not like having their photos taken as they think you are making money from their images. So, either be surreptitious or, better still, just give them what they believe is their share of the profits.

Entry visas are now available online; all you need is your Yellow Fever certificate. And malaria is present so take your Malarone pills. The national language is officially English. Credit cards are accepted widely in Kampala and Entebbe but otherwise you will need Uganda shillings, which will cause you to become an instant millionaire with one trip to the ATM (also really only available in Kampala and Entebbe).

Kampala

Kampala looks and feels exactly what it is: a massive – 7m people are sprawling over 9,000 square kilometres – modernising – skyscrapers are starting to dominate – important city that is not only the national capital but rapidly emerging as one of the leading lights of the region. To casual visitors, its defining feature is likely to be the hideous traffic congestion; and it is a unique thrill to take a motorbike taxi (known as a boda boda), on which helmets are a rarity, ducking and diving at great speed around lines of gridlocked cars on tarmac roads that suddenly dissolve into rutted muddy tracks. But with a little effort you can start to get at this extraordinary city with a storied history, an emerging cool urban vibe, and several interesting typical tourist sites.

Safari operators tend to advise staying in small town Entebbe rather than Kampala because of this congestion, so many visitors never come here at all, even though the hotels here are much better. There are three five-starred. The best in the country is the Serena, right next to the construction site for the new parliament, a little along from the current parliament building. Its conference centre was used for torturing opponents of Idi Amin in the 1970s. The hotel itself has bars and restaurants around a forested courtyard that nightly hums to a frog chorus, a calming outdoor pool, one of the best gyms on the entire continent, and a sauna ideal for a refresh after weeks in the bush. The Pearl of Africa Hotel, only five years old but already an established silhouette on the skyline, is not far from the State House, the President’s official residence and office, hidden behind walls and trees, surrounded by road blocks. The Sheraton, near the Independence Monument, is not in the same league but it is a historic landmark because when it operated under its original name of Apolo it served as the headquarters of the occupying Tanzanian army after they defeated Amin.

Kampala also has an emerging contemporary cool side. For example, Latitude 0° is where Soho House meets WeWork and comes away with a distinctly African chic; apart from us, there were no westerners here. It is not far from the old skool Makindye Country Club. There are also a number of stylish cocktail bars and plush restaurants in town, especially in the Kololo neighbourhood along and off Acacia Avenue, formerly the colonial living quarters, not far from the golf course and the Uganda Museum. The standout is the Lawns, billed as fine dining on game meat; dishes include stir fried buffalo, antelope stroganoff, and a tasting menu called the Serengeti Plains Platter. It is generally delicious (though buffalo is tough), healthily low in fat, and not poached in the wild but reared on ranches. Another symbol of modernity is the Café Javas chain for salads and smoothies in a terrific local atmosphere.

Owino is one of the great markets of Africa. Reputedly a den for pickpockets, which may explain why we saw no other foreigners here at all, it is a hubbub of activity. There is massive section of second-hand clothes and shoes, with on-site sewing machines for immediate alterations and repairs. There are vast vats of peanut butter, made before your eyes, hundreds of chickens crammed tightly into cages, and curtains of hanging raw meat all mixed in with knock-off English Premier League replica shirts and Luis Vuitton bags.

A good place to get perspective on all the chaos is the National Mosque, the largest in East Africa, right in the centre of the city. According to the latest census, 14% of Ugandans are (mostly Sunni) Muslims. This is also known as the Gaddafi Mosque as it was built by the Libyan dictator in 2006. It is impressive in its own right, and in addition the view from the top of its minaret gives a spectacular panorama that will help you get your bearings on the mayhem below, with clear sight of the seven hills on which Kampala was originally built.

Atop one of those hills, Namirembe, is red brick St Paul’s Cathedral, the oldest extant church in the country, which also has good views of the city. The census says the remaining 84% of Ugandans are Christians, and of those 32% are Anglican. There were four previous churches built on this site between 1890 and 1904, but each were soon destroyed – in turn by swampy foundations, strong winds, termites and lightning – before this one was erected in 1919. When we were there on the holy day, it was packed to the rafters with people in their Sunday best in a way that few European churches enjoy.

Of the Christians, 39% are Catholics, and on top of another hill, Lubaga, the landmark St Mary’s Cathedral was constructed by French missionaries in 1925.

Also important historically in Uganda has been the Baha’I faith, established in Iran in the nineteenth century, which seems to profess the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Amen. In any case, they were banned and their leaders were murdered by Amin, although their community has started to revive again recently. The faith has only a dozen or so temples worldwide but they have a nice octagonal one in Kampala, built in 1961, up by the northern ring road about 3km from the golf course.

The Kingdom of Buganda formed the backbone of the British Protectorate of Uganda, though it was abolished in 1966 after independence. However, after years of political instability and military conflict, it was officially restored in 1993, with a largely ceremonial function. Its largely ceremonial parliament, the Lukiiko, sits in a building, the Bulange, put up in 1958 towards the end of British rule. It is an impressive structure locked behind iron gates, though 20 shillings will grease the palm of the guard enough to get you through to have a look around the outside.

Ever since restoration, the Buganda king, or Kabaka, has been Muwenda Mutebi II, the 36th in succession. His office is in Lubiri Palace, built in 1885, at the other end of the Royal Mile that sweeps down the hill from the Bulange, through the gate that is only opened for his royal procession, and on up to Mengo. The route is lined with statues of the animals representing each of the 52 clans that compose the Buganda Kingdom.

Lubiri Palace was seized by Milton Obote, the first Prime Minister of independent Uganda, after a power struggle when he drove into exile Freddie Muteesa II, the then Kabaka – and first President of the country – and established the Republic of Uganda in 1966. It was subsequently occupied by Idi Amin when he declared himself President. In 1971 he had built in the lovely garden of local fruit trees an underground armoury that a year later was converted into an horrific torture chamber that used electrified water on his political opponents; it is estimated that in these five cells his soldiers murdered almost 20,000 Ugandans. When Obote assumed power for the second time, in 1980, he took over Lubiri and it is believed that his soldiers then murdered 16,000 Amin supporters there. You can visit both palace and torture chamber with a guide who will mince no words.

Four prominent former Kabakas dating back to 1884, including Freddie Muteesa II, are buried in the Kasubi Tombs. This is one of only three UNESCO World Heritage Sites in Uganda, anointed particularly because the main edifice at its centre, Muzibu Azaala Mpganga, with a 31m diameter, is the largest thatched roof building in the world. Sadly it caught fire in 2010 but after more than a decade of reconstruction it is opening step-by-step.

Jinja

It is two hours east from Kampala to Uganda’s second largest city, Jinja. There are several very good reasons to come here, typically on a day trip: this is the official source of the White Nile; there are boat tours of Lake Victoria, which has excellent birding; and the white-water rafting on the early part of the River Nile is easily accessible and world class.

Identification of the exact source of the White Nile is attributed to the English explorer John Hanning Speke in 1862. He pinpointed it as Rippon Falls, a narrow opening from Lake Victoria in the south of Jinja. However, Rippon Falls were completely submerged in 1954 when the Owen Falls Dam was completed, so today the spot is marked by nothing more than a small hut with a sign and a curio shop on a tiny lump of land called Rippon Island. Although it certainly does not live up to its billing, tour boats constantly pull in for the obligatory photograph.

These little boats do not need to be booked in advance. They leave the jetty near the statue of Ghandi that marks where some of his ashes were spread (they were dispersed in four of the world’s great rivers). The ride to the source is only five minutes from shore, though the trip is enlarged into an hour-long cruise of Lake Victoria (the largest freshwater in Africa, and the second largest in the world, after Lake Superior). Guides point out dozens of important bird species found here, including rock pratincoles, African open-billed storks and Western banded snake eagles. The water is also full of fishermen in boats with both nets and hand-held lines. The best place for a sundowner is Jinja Sailing Club, and the town’s own Nile beer is excellent. Uganda also has several popular craft beers, notably Banange, along with Waragi gin.

The Nile flows at a speedy average of 70km a day, taking three months to travel north the entire 6,600km of the longest river in the world before emptying into the Mediterranean at Alexandria. It is only about 5km up river to a lengthy section of rapids that are ideal for rafting and kayaking. There are plenty of local operators; we went with White Nile Rafting, a big firm that does long half-day (8am to 4pm) and longer full day (to 6pm) trips with half-a-dozen people per boat, each supervised by an experienced captain and a flotilla of safety kayaks.

Entebbe & Around

Entebbe, a tiny town of 70,000, 35km south-west of Kampala, is home to the country’s only international airport. The older airport next door is these days used mostly by United Nations planes and for some internal flights, though it is famous as the scene of a successful and bloody Israeli hostage rescue in 1976.

Jutting out on a peninsula into Lake Victoria, Entebbe was the seat of government for the British Protectorate of Uganda from 1894 to 1962. Although there are few relics of that era left, the president maintains another State House here for receiving dignitaries, hidden away behind thick foliage and heavy security.

There are no particular reasons for visitors to come here other than as a more accessible base than congested Kampala from which to reach the western attractions, near and far. There are luxurious resorts on Lake Victoria – notably the Protea Marriott, on White Sands Beach – and a serviceable authentic option popular with the safari operators is the Boma, a lodge set in tropical gardens.

There are sunset cruises out of Entebbe as well as Jinja, leaving from the marina, and there are also several decent places between the Botanical Gardens and Entebbe Beach to sit with a beer on the coast. The most popular are 2 Friends, which serves excellent tilapia, the prime fish of the lake, and Goretti’s, a pizza joint.

It is an hour or so west of Entebbe to Mabamba Swamp, an extensive wetland in the outer showers of Lake Victoria. This is an essential destination for birders as there are more than 250 species, many of which are threatened, but it is also appealing for non-specialists because this is the best place to see the unique and elusive shoebill stork. These extraordinary creatures can stand up to 1.5m tall, with a 2m wingspan, and weigh as much as 5kg. They live in the swamp, which has relatively low levels of oxygen in the water so fish need to come to the surface to breath, where the shoebills can pounce. Slender motorised canoes head out through narrow canals between immense bushes of papyrus reeds, a stunning journey in its own right, then paddle quietly to within a few metres for spectacular close-ups of these great birds.

It is an hour-and-a-half on again to the town of Kayabwe, where everyone has their photo taken at the equatorial line. The equator passes through twelve other countries (Kenya, Somalia, Maldives, Indonesia, Kiribati, Ecuador, Colombia, Brazil, Sao Tome & Principe, Gabon, Republic of the Congo, and Democratic Republic of the Congo), though not in all of these on land or with marker signs. In Kayabwe, there are two large circles on either side of the main road identifying the line, which extends into the Equat0°r Line restaurant, where tables have been set up to allow you to sit with a foot in each hemisphere. There is also, inevitably, a string of souvenir stores.

The earth rotates faster at the equator than it does at its poles, and this fact has some fascinating consequences in physics. For instance, this is what causes hurricanes to spin anti-clockwise in the Northern hemisphere and clockwise in the Southern; it also means aeroplanes and bullets, whether travelling north or south, veer slightly to the right in the Northern hemisphere and to the left in the Southern. The Coriolis Effect shows that this so-called deflection rate decreases as latitude decreases, until it is zero at the equator itself. In Kayabwe, a guy with three basins and a hat to go round repeatedly seeks to demonstrate the truth of this proposition: water emptied through a basin plughole into a bucket only a couple of metres into the Northern hemisphere appears to drain clockwise, while a couple of metres in the Southern anti-clockwise, and on the equator it just goes straight down. However, do not be fooled. In truth, the Coriolis Force is too weak to show such differences so close together, so this is in fact a conjuring trick reinforcing an Old Wives’ Tale, though a highly entertaining one.

Murchison Falls & Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary

It is a six-hour straight drive on a good tarmac road from Kampala to Murchison Falls in the north-west of the country. There are many roads under construction around here, primarily to service the ten oil rigs that tragically have just started drilling in Murchison Falls National Park, which unfortunately has 40% of the country’s oil reserves that were discovered as recently as 2006. There are also one-hour flights from Entebbe’s old airport 350km to any of three airstrips in the Park, the scene of not one but two plane crashes in a week in January 1954 for Ernest Hemingway.

Murchison is the most powerful waterfall in the world, where the broad River Nile is forced to squeeze through a tiny 7m gorge before crashing down 45m at an astonishing rate of 300 cubic metres per second. There is a small walkway at the Top Of The Falls from where you can peer, damply, through the permanent rainbow into the plunge pool.

At this point, the Nile flows east to west, from Lake Victoria to Lake Albert on the border with the DRC. There are several lodges beautifully situated on it, including Murchison, Nile, Paraa and Twiga, all of which have jetties for two-hour guided boat tours up to the delta at Lake Albert; on Google Maps there is a vast area on the north side of the delta simply labelled “hippos”. It was around here that African Queen was set and shot.

Murchison Falls National Park is the first (it was gazetted in 1926), biggest (of ten) and most visited (as many as 50,000 people came each year before Covid) game reserve in the country: it covers almost 4,000km2 and the Nile flows through it for 115km. There are more than 450 known species of birds, including Goliath herons, secretary birds and yellow foot kingfishers. In addition, there are 450 tree species, 250 butterflies, 76 mammals and 13 primates. It is possible to spot four of the Big Five here and shoot vaguely usable pictures of them even on an iPhone. Among them, buffaloes are, surprisingly, the biggest killers of humans.

Due to ivory poaching and military conflict, the number of elephants in the park plummeted from about 16,000 in 1970 to under 500 by the millennium.

Numbers of lions were not officially counted until 2009, when there were about 600. Today, there are only 400, a decline of one-third in less than fifteen years.

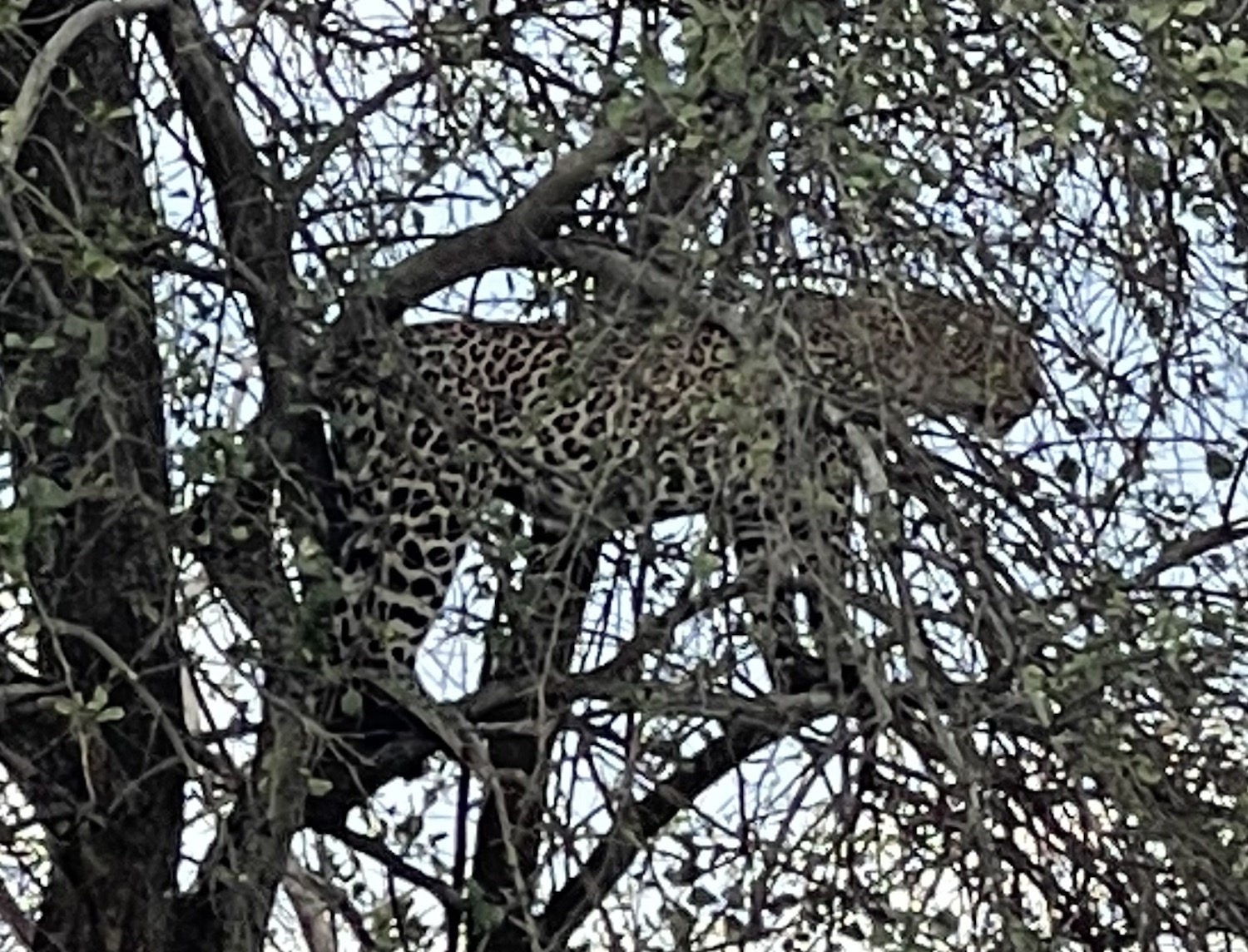

Leopards are famously hard to spot. Early one morning we came across a recently killed oribi antelope dangling from a branch in a tree with very few leaves close to the road. We assumed a leopard must be nearby and sure enough when we went back to check in the late afternoon this one was standing quite openly, ready to eat its meal.

Half way back to Kampala from Murchison Falls is the Ziwa Rhino Sanctuary, the only place in the country where you can complete Big Five bingo. Rhinoceroses became extinct in Uganda in 1983. A white rhino pair from Kenya were reintroduced in 2001 and a couple of others from the US soon after. They were kept in a zoo until this 70km2 park opened in 2004. The first Kenya-US rhino calf was born in 2009 and it was inevitably named Obama. Today, there are a total of thirty-three individuals who live in small family groups under 24-hour armed surveillance to protect them from trophy hunters.

The difference between white and black rhinos has nothing to do with their colour as they are all shades of grey. The label “white” appears to have originated from a mistranslation of the Afrikaans word “weird”, which referred to their wide lips used for munching grass as opposed to the hook-shaped lips of the others used for eating leaves from branches, which became called “black” simply to differentiate them. In addition, white rhinos are larger, have a longer front horn, and live on the savannah, rather than in the forest, making them easier to see.

At the Ziwa Sanctuary, guides lead small groups on regular two-hour walks in gumboots through the open plains. During the day, white rhinos mostly sleep so we were lucky to come across a family wandering about grazing. They are obviously intimidatingly powerful, and can charge at up to 45kmph, but white rhinos have poor eyesight so we were told we would be safe in the event we needed to step into a bush or nip behind a tree.

Some people come to Uganda just to tick off the Big Five in the north-west. As you like it. However, the essential excitement of coming to this country is from putting in the effort to enjoy animals and experiences that cannot be found in other places. Apart from Kampala, Jinja and around Entebbe, that primarily means the forests of the west and south-west.

West & South-West Safaris

It is a one-hour flight in a little Cessna Caravan over the 320km from Entebbe’s new airport to the little town of Kasese. We flew out on the 7am Aerolink, the only two passengers in the plane’s eleven seats so we had all-round views over the Entebbe Peninsula, Lake Victoria, the rolling hills smothered in mist, and then the canopy of the jungle looking like broccoli.

We drove back through the bush from Bwindi, breaking the 12-hour return to Kampala – on murrum dirt roads, under-construction roads and even some actual tarmac roads – at Lake Mburo. This is where you can find the last pair of white backed night herons and the endangered African finfoot. It is also an ideal spot to see your common and garden safari mammals including zebra, giraffe, eland antelope and impala gazelle, as well as highly unusual longhorn Ankole cattle.

Kasese is in the shadows of the Rwenzori Mountains, the highest range in Africa and the second UNESCO site in Uganda. The biggest is Mount Stanley, at more than 5,000m the third tallest in Africa, and several other peaks are also permanently covered in ice so the trails are more for climbers than trekkers. The range stretches for over 100km and much of it serves as the border with the DRC.

There are occasional police checks that increase in frequency the closer the border you get, though they are usually light touch. Around here you may well see yellow-uniformed prisoners working on the fields like a chain gang. We certainly had semi-dressed kids running from their wooden homes to wave at the muzungu as we drove past. The fields are full of fruit and veg, most obviously the more than twenty different varieties of bananas, jumbled together with plantains, all with leaves and fruit so similar that only an expert can tell them apart. The roads are buzzing with motorbikes and creaking with bicycles over-laden with hundreds of bananas being taken to market.

Plantains are boiled and mashed as matooke, a popular meal. Some of the banana types are too hard to be eaten in the traditional manner; instead they are pulped with a grass to extract their juice that can be drunk neat or at makeshift banana breweries distilled into a rather tasty beer called tonto that is served in a calabash cup. Bonga.

Rural village weekly markets are a riot of colour, noises and smells, still lively if less claustrophobic than Owino in Kampala. There are cows’ bloody innards, bits of skin-covered legs and even severed heads lying on benches outside the hut that serves as the abattoir, and heaps of dried fish near the row of thatched rooves without walls that act as restaurants, next to the mounds of flip flops home-made from old car tyres. In addition to bananas and plantains all the local fruit and veg is piled high: cassava, guava, jackfruit, yams, avocados the size of pineapples and pineapples the size of melons.

Kasese is the gateway to the road north that takes in the Crater Lakes and Kibale National Park for the chimpanzees, and also south through Queen Elizabeth National Park to Bwindi Impenetrable Forest for the gorillas.

The drive north takes you past many of the 50-odd beautiful Crater Lakes in this area that were formed 8,000 years ago when the lava tops blew off extinct volcanoes, leaving large basins of water. The most iconic is Nyinambuga, surrounded by eucalyptus and vanilla trees, which is pictured on the 20,000 shilling bank note. That view is from the Top Of The World souvenir stall by the main road to Fort Portal. There are hiking trails all over as are black and white, and red, colobus monkeys, red tail, grey cheek and blue monkeys, as well as friendly vervets and scavenging baboons. The red colobus are endangered, partly because of human encroachment causing habitat loss, but also because they are the famous drunken monkeys which eat certain leaves that can leave them befuddled, at which point they get picked off and eaten by gangs of chimps.

The place to see the chimps up close is Kibale National Park, the entrance to which is about two hours north, mostly on a dirt road, from Kasese. There are loads of lodges around here, the best of which seem to be Chimpanzee Forest and Turaco Treetops. There is also a series of bar shacks with wonderful names including “Cool”, “Good Shade”, “Nice”, and “Surprise”.

Kibale, like Bwindi, is surrounded by ragged coffee bushes and neat tea plantations in patchwork quilt patterns. This is encouraged because chimps, gorillas and monkeys do not eat tea leaves and elephants find it hard to traipse through them, making them a natural barrier for the reserves.

Chimps are our closest relatives, with a 98.7% DNA match, and there are about 1,500 of them in Kibale, of which around 10% are wild but habituated to human interaction. Guided trackings leave the park office at 8am and 2pm each day. You need to buy a permit in advance, which limits numbers to about twenty-five per half-day. You are then given strict rules (wear a mask when you get close to prevent the spread of human diseases, especially Covid, and do not mimic their vocalisation on the grounds that you do not know what you might be saying to them) and you are allocated to a group of half a dozen with a ranger (plus an armed escort, just in case). There are no beaten tracks; you just charge across the flat dense jungle listening for calls.

It can take up to a couple of hours to locate them though within twenty minutes we accidentally awoke an alpha male dozing on the ground. He is the president of a troop of about a hundred individuals and we soon found another dozen partying in the neighbouring fig trees. Theoretically, we were limited to an hour with them and restricted to an 8m distance, though in reality we were there about two hours and got to within a couple of metres. In a footnote, some of the early Johnny Weissmuller Tarzan films were shot in Uganda and I never understood why his chimp was named Cheeta.

This whole area is a paradise for birding specialists, with 375 species including rare blue-headed bee-eaters, Cassin’s spine tails, great blue turacos, masked apalis, Nahan’s Francolins, Prigogine’s ground thrushes and above all green breasted pitas. Although the grey-crowned crane is common, it is the national bird and appears on the national flag.

Just south from Kasese is another equator crossing. This time there is simply a cardboard cut-out of the circles from Kayabwe and another guy with the three-basin Coriolis Effect trick. Soon after is the start of Queen Elizabeth National Park, which is only 5k from the border with the DRC. There is no doubt where to stay here: Mweya Safari Lodge, on a hilly headland between Lake Edward and the Kazinga Channel that flows from it to Lake George 32km away, with views from the club bar, terrace restaurant and every room of the iconic African scene of elephants and buffaloes bathing at the water’s edge. The Queen of England stayed here in 1954 when the park was re-named, and signs in the car park tell you to check under your vehicle for banded mongoose before starting the ignition. What more do you want? Oh, and the drive out to it is full of game coming and going to the water on either side.

The Kazinga Channel is only about 8m deep though it is wide and full of life. It is home to hundreds of crocodiles and an estimated 2,000 hippopotamuses (we probably saw about half of those, including this two-days-old calf), as well as more than a hundred species of water birds including white pelicans, pied kingfishers and yellow billed storks. Boats leave the jetty below the Mweya Safari Lodge for two-hour round trips, one of the outstanding highlights of this whole country.

To access the 2,000km2 of Queen Elizabeth National Park itself you buy passes in multiples of 24-hours for game drives. I recommend the “experiential ticket” that gives you a GPS big cat tracking device and the right to go off-road to get closer to the wildlife. Do not miss the popular spot for a picnic lunch at a gorgeous part of the Ishasha River that is loaded with hippos and at no more than 10m wide marks the border with the DRC; there is an army encampment made from little grass huts nearby. It is obvious at first glance that the elephants around here are much more aggressive than in Murchison Falls, apparently as a consequence of their roaming across the border and encountering hostile human activity.

There are lions all over Queen Elizabeth National Park, and like lions everywhere they can and do climb trees, though they are never as adept as say leopards. Yet in the Ishasha Sector, which is three hours from Mweya Safari Lodge in the far south-west of the Park, they are marketed heavily as “tree climbing lions” because the branches of the fig trees start so close to the ground that they are easy to jump onto. However, there are only thirty lions in that 400km2 area so your chances of seeing one – up a tree – are slim.

It is another two hours south on a rocky and dusty road through steep hills covered in banana fields and tea plantations to Bwindi. The road is full of bedraggled children with homemade scooters, women in colourful kitenge with straight backs and baskets of corn on their heads, and men on little battered motorbikes heavy with bundles of fruit and veg.

Aptly and evocatively named, Bwindi Impenetrable Forest is the third and final UNESCO site in Uganda. It is 330km2 of the Western Rift Valley in the Kigezi Highlands, more than half of it over 2,000m above sea level, undulating with brutal slopes of as much as 45° inclines, creating a montane ecosystem. It has an annual rainfall of about 2m, and it is often soaked in mist, fomenting a biodiversity thick with one thousand species of flowering plants, including two hundred species of hardwood trees and one hundred species of ferns. And, of course, it is home to 400 endangered mountain gorillas, up from 300 twenty years ago. This is roughly half the world’s population; the rest are in the nearby Virunga Conservation Area shared with Rwanda and the DRC.

There are fourteen habituated groups open to visit in four sectors: Buhoma, Nkuringo, Ruhija and Rushaga, which all have lodges nearby. We tracked in Ruhija, where there are four groups. The process is similar to chimp tracking in Kibale, but a whole lot more serious. Permits, which are restricted to forty people per sector per day, are booked up months in advance. Groups are limited to eight people per guide plus two armed rangers (essential since the turn of the millennium when fourteen foreigners and their guide were captured here, and half were later murdered, by Rwandan guerrillas trying to warn off tourists from coming to the region). In addition, everyone is allocated a walking stick (which also turns out to be essential) and a porter from the local community (whether you need one or not). Porters carry your rucksack (which really contains only some water, a packed lunch, and a raincoat in case of sudden showers) and offer an occasional hand, a pull or a push on the muddy hills. The minimum fee is US$15 though if you end up having to be carried they will charge more on a sliding scale proportionate to your weight, and if you need a stretcher it is US$300. Two trackers go out in search of each group a couple of hours before you set off around 9am, and there is a limit of nine hours to find them.

No outsider had seen a gorilla, with whom we have a 98.4% DNA match, until the French explorer Paul Du Chaillu in 1856, and no amount of David Attenborough or Dian Fossey can prepare you for sitting just a metre from a fearsome silverback or being pushed aside by a passing mother with a little infant clinging to her.

When Bwindi was reclassified as a national park in 1991, with a range of measures to protect the gorillas and the opening of its gates to tourists, there was a life-changing impact on 6,000 Batwa pygmy people. One of the oldest surviving indigenous tribes in Africa, which had for centuries lived as nomadic hunter-gatherers in the forests of Uganda, Rwanda and the DRC, they had been major killers of gorillas and other threatened animals, as depicted in Gorillas In The Mist. So they were evicted from their ancestral forest homes, though this in turn has caused them to become endangered refugees themselves.

Genetic changes to bolster immune systems against microbes prevalent from forest dwelling seem to have the by-product of also hindering physical stature. In addition, poor nutrition and high stress have generated a life expectancy of just 28 years, triggering further genetic changes to prioritise the development of early reproduction capabilities at the expense of teenage growth spurts. These are two of the most likely reasons why pygmies have an average height of less than 1.5m, five feet.

Over the past decade, various Batwa “empowerment village communities” have been set up by the government and supported by NGOs. We visited the one in Buhoma. I found it excruciating. We were met by two men in loincloth wielding spears, who then gave a camp demonstration of how their ancestors hunted for bushmeat. We – and two other visitors – then watched a traditional music and dance performance, in which some foreigners idiotically join in under the patronising delusion that it is a gesture of welcome. Our local guide explained that donations are needed to continue programmes of skills training in contemporary agriculture, sewing and tailoring, basket-weaving and craft-making, before leading us to the gift shop to purchase these products along with tribal masks smuggled over the border from the DRC.

This photograph says so much about the ancient and the current in this part of Africa. The guy without shoes in the snazzy headgear to my left is the Batwa king of this pygmy village. The two gentlemen carrying AK47s – Gerald and Stanley – had been protecting us for a while. I can only wonder what the little girl must be thinking.

Thankfully, there are no mountain gorillas in captivity these days. As with all these other magnificent creatures throughout Uganda, instead of stealing them away to zoos, civilization is reaching a happy medium that protects them in their natural habitat while allowing scientists and visitors to encounter some of them in controlled conditions. However, we do not seem remotely close to that balance with these important human communities. Obviously Batwa pygmies can no longer live free in the forest hunting endangered species. But since being exhibited in the Bronx Zoo in New York City in 1906, they have recently suffered genocide in Rwanda and they are still being enslaved to Bantu masters and are victims of cannibalism in the DRC. Surely there is a way in Uganda today of integrating them into society, while preserving their culture, without turning them into circus performers. Why basket-weaving? What about coding?