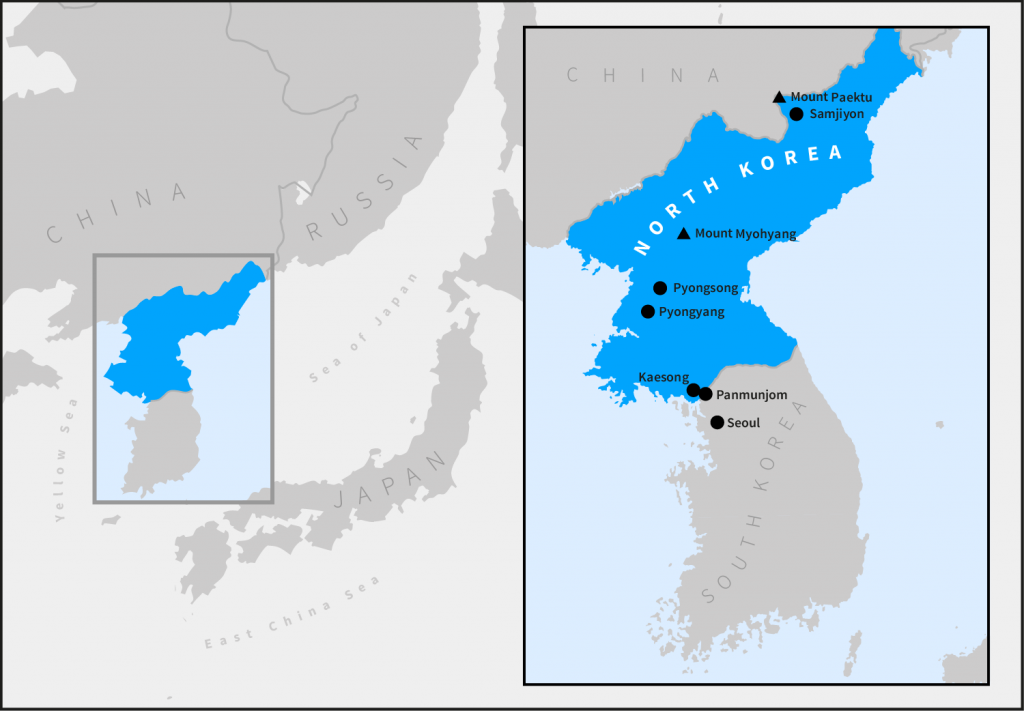

Having spent almost two weeks in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea in 2016, I came back. The trigger was to experience the Mass Games, the vast annual performance of synchronised gymnastics that had been abolished in 2013 but is now reconvened. I was also interested to see if anything had changed since I last wrote a review of North Korea; after all, this had been a period of widely publicised missile launches followed by high profile talks between Presidents Kim Jong Un and Trump. And I was surprised by some of what I found: there are small signs of economic development, with new buildings and more cars, even the green shoots of a consumer culture, as well as an unexpected but concerted effort to play down the warmongering and hatred of America in local propaganda.

At root, North Korea is politically, culturally and even economically still stuck in 1953, when the national mythology was founded that Kim Il Sung liberated the country first from Japan and then from America, despite the treachery of the South. This story has been supplemented from a time in the 1990s when Kim Jong Il battled bravely in what is known locally as the “arduous march” after the collapse of the Soviet Union to keep the DPRK independent and socialist, despite the acknowledged economic hardship caused by the loss of trading partners and the imposition of sanctions.

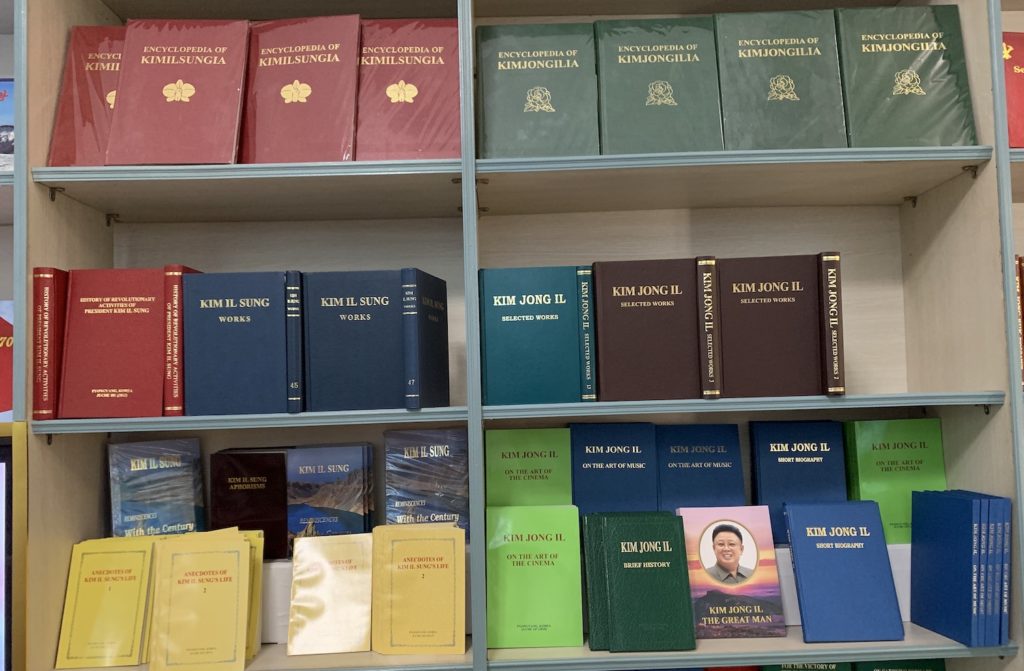

These two Kims are deified in tens if not hundreds of thousands of statues, mosaics, paintings, badges, operas, songs, TV and radio programmes, eponymous buildings and a creative array of other monuments that assault the senses of every North Korean every minute of every day.

After eight years in power, Kim Jong Un is beginning to assert his own place in this story, with the emergence of a new personal iconography along with the increasingly brutal political regime that permits zero dissent, even from close aides and family members, who are routinely purged. His claim is to be defending North Korea through a powerful army, creating an economy that is becoming self-sufficient, and developing a scientific capability that is modernising the country.

Leaving the rest of the world behind

Still the only way into the country is via a travel agent based in Beijng. Again we used the excellent Koryo Tours, which months in advance set up a private schedule of activities that the two of us requested. It is a requirement to attend an induction at their offices where we were reminded of the basic rules for tourists: do not give your opinions about the Kim leaders, religion, nuclear weapons, defectors, or prison camps; do not take photos of the Kim statues, of which there are many, other than from the front-centre within an angle of 45 degrees and always of the whole body not just a part, like the head; do not take photos of construction sites or department stores; do not fold, tear or throw away any publications containing pictures of the leaders, and they all do; and do not point, though this is the default position of the Kims in literally thousands of photos and paintings.

Koryo Tours also arranged our visas, which are no longer put into our passports because of rumours that those with North Korean stamps would be denied ESTAs for automatic entry into the United States; a contrary threat amid the current supposed detente.

The Air Koryo (Koryo is the Korean word for Korea) flight from Beijing to Pyongyang takes ninety minutes. Both out and back it was three-quarters full, mostly with Chinese tourists, a few North Korean elite and a score or so Europeans; since I was last here, in another counter-intuitive move, the American authorities have banned their citizens from travelling to the DPRK. We arrived during the seventeenth biennial Pyongyang International Film Festival, showing local and international movies, including a selection of latest Bollywood hits, so it is likely there were more foreigners than usual. There is obviously a prettiness threshold to become a flight attendant on these planes, and like every North Korean over the age of 14, at all times they have to wear a badge over their heart picturing one or both of the first Kims wearing benign smiles. We are reminded there are no photos allowed of or from the plane.

What is noticeably different though is that on the drop-down TVs we are not entertained by military parades and marching army bands. There is instead a reel of Pyongyang’s many tourist highlights: the 20m-tall Mansudae statues of the Kims where we along with everyone else have to bow and lay flowers, the 46m Chollima Monument to the advance of the socialist society, the 50m Party Monument commemorating the might of the Workers’ Party of Korea, the 170m Juche Tower symbolising the ideology of isolated national self-reliance, the enormous Kumsusan Mausoleum where the two late Kims lie embalmed on view, the gigantic Victorious Fatherland Liberation War Museum telling a version of the 1950-53 Korean War with America, and the vast but empty Kim Il Sung Square where troops and weapons are paraded on ceremonial occasions.

These immense memorials can make Pyongyang feel like a tourist’s theme park and a photographer’s dream, while just under the skin is a very dark place.

Also shown on the plane are a series of softer images of sun rises, scientists in lab coats, parents and teachers surrounded by smiling children. In fact, we did not see any military bands or soldiers on TV in Pyongyang either, whereas three years ago that was more or less all we saw. However, on one day we noticed the TV schedules were cleared and devoted to revering the wife of Kim Il Sung as it was the anniversary of her death in 1949.

The security checks at Pyongyang airport are much more rudimentary too. Of course our suitcases were opened and we had to take everything out for inspection, but it was all rather cursory. My guide books to China were initially removed but an English speaking soldier soon said they were fine. We were allowed to take mobile phones and laptops, safe in the knowledge that there would be no connectivity, though this time nobody bothered to check our emails or apps or photos to make sure we were not bringing anything seditious.

Just like last time we had two guides and one driver, mostly to report back on each other rather than the two of us. They emerged from the crowd at the airport arrivals gate, immediately confiscated our passports, and from that moment until we were deposited back in the departures hall we were hardly ever allowed more than a few paces away from at least one of them during the entire trip, including while going to the toilet.

Almost the only place we were left to roam alone was at the Yanggakdo Hotel, where virtually all international visitors are marooned on an island in the middle of the Taedong River that slices Pyongyang east and west. In training for an upcoming marathon, I was allowed to run only the 200m up and down the car park. But from our 41st floor room, and the restaurant on the top, we had wonderful views across the city, especially first thing in the morning as the colourful buildings rise out of the mist like Brigadoon.

The other landmark hotel in town is the 105-storey Ryugyong, a 330m pyramid skyscraper that dominates the skyline more or less everywhere. Construction started in 1987 and it is still not open, though since 2018 the North Korean flag and various propaganda symbols and messages are projected onto it in an impressive nightly light show.

This is not the only hotel unfinished: near Kim Il Sung Square there is a big building behind corrugated iron barriers which lies derelict after, we are told, its Chinese financiers recently withdrew.

The Kim iconography hits us slap in the face straight away. The same pair of giant portraits of Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il adorn the outsides of hundreds of public buildings as well as the insides of all buildings, from homes to children’s nurseries. Everywhere we visit has a gift shop, always selling the complete works of the Kims.

The clothing is still drab. Nobody wears jeans, the unofficial uniform for women seems to be a black pencil skirt and nearly all the men wear dark blue or grey suits, with short sleeved jackets and wide flares.

There are still strict security controls. Our minibus is stopped each evening by traffic police to check that our guides have the necessary paperwork.

Lying is still in vogue too. At dinner one night I asked if I could have the most revered dish in the city: Pyongyang cold noodles. I was told that this restaurant did not serve it. But I could see it on the menu and when I pointed to a plate of it on the table next to ours I was told that it had been brought from another eatery.

Our guides

Our two guides were women in their late twenties with contemporary personalities and modern attitudes that could fit into any world city quite easily. They have big English vocab, perfect pronunciation, and know exactly how far to push it. For example, while they always kept us from walking too far from the agreed route, when we asked about some music that was piped into a public square we were told with a shrug that it was just propaganda to motivate the workers.

They also have big sunglasses, fake Louis Vuiton bags, and kitten heels. Beautiful and elegant, I saw plenty of local young men ogling them as they walked by. And these days they have big smartphones too, North Korean models with a camera, SMS facility, and an intranet for swapping photos, reading newspapers and watching films, though obviously the internet is blocked.

One of them was happy to tell us that at 26 she was not yet ready to get married “because I enjoy my freedom too much”. That is why she had already rejected the first boy that her parents had arranged for her to meet as a possible husband.

They talked about which clothes and which sports are currently in fashion – apparently ten-pin bowling is out and tennis is in – a concept unfathomable to older citizens. They reported that the “younger generation” are less obedient, and prefer burgers and pizza to local food. And to my amazement they went out of their way to tell us that foreign lesbians and gays are very welcome on trips. This is despite the fact that while LGBT people are not de jure illegal in the penal code, they are effectively prohibited from coming out by obscenity and indecency laws and there are reports of executions, so couples have to be extremely covert.

It was incongruous, and deeply sad, that these modern women would then without blinking lecture us on the merits of revolutionary songs, socialist economic planning, collective farming, and putting the army at the centre of national life. And although it felt like a breakthrough of intimacy when one of them suggested we go swimming with her in the wonderful antique Changwangwon Olympic-sized pool, we were taken aback when she appeared from the changing rooms in a 1950s modesty costume with hat and dress in canary yellow.

One of our guides told us she had graduated in British and American Studies and she was keen to understand what was going on in today’s turbulent politics. She wanted to know what the western media said would happen next between Trump and Kim, and Trump and Iran. She asked how Boris Johnson became Britain’s prime minister. Well, I explained, there was no national election, he was selected by a majority of his party’s members. “Like in China,” she responded. She also told us that she knew from local TV and foreign tourists that Johnson is “embarrassing” and “racist” and that Britain has gone “crazy”. She talked about the Hong Kong protests and could not understand how the airport is often allowed to be closed these days.

Signs of change

To our surprise, Pyongyang’s iconic “traffic ladies”, hot but severe young women who stood in the middle of the road controlling vehicles with a firm stare and a point of their batons, are no more. They were finally swept away by the installation of traffic lights in 2018. All that remains are a few camply dressed men in jackets with flashing lights who patrol the main streets at night. Although most people still get about by bicycle, there are noticeably more cars, and taxis, on the newly tarmaced roads, despite petrol sanctions.

Similarly, there are lots of new buildings all over the city, and panoramic views reveal a forest of cranes putting up many more. Of particular pride to our guides is Changjon Street in the Ryomyong neighbourhood, where a cluster of contemporary-looking apartment towers, in shades of bright green in keeping with the blues and reds and yellows of Pyongyang architecture, have sprung up, they say in the past twelve months. These stylish showcase skyscrapers apparently house 4,300 families at an average of four people per 100-120 square metre apartment. Our guides are especially anxious to tell us that they are CO2 neutral, they use solar and geo-thermal energy, and they recycle rain water. Which all makes Pyongyang feel very modern until you spot a flotilla of army trucks driving by.

On our previous visit we were permitted into only one proper retail outlet, the Kwangbok Department Store, where we were given just €5 in the local won currency to spend, and we had to return the change at the end. This time we were allowed into many and could have as much won as we wanted. The exchange rate varied considerably, though: in local shops we got 8,000 won for €1, but in the hotel and stores with imported goods we got just 100. These places also accepted euros, dollars and Chinese renminbi, but not British pounds.

We went into several grocery stores where the fruit and veg seemed plentiful and fresh, which is hard to plant as props just for foreigners. Sunrise supermarket on Tangden Street, which apparently serves the foreign diplomatic community, was particularly well stocked with high quality produce, including European tins and jars, but it was very expensive and completely empty of customers.

In the Taesong Department Store, there are Chanel, Dior and Lancome cosmetics, Johnnie Walker whisky and Bolinger champagne, non-vintage at €55. There is a large electronics department with Canon and Nikon cameras, Dell and HP computers, Phillips and Sony TVs, as well as Siemens fridges and Dyson blade-less fans.

It is not clear who buys this stuff. Especially the Rolex watches, priced here at 6,000,000 won. Nor is it clear how these goods managed to sneak through the global trade embargo. We also saw bags that claimed to be made in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.

Old habits die hard though. In the Ragwon Department Store beautifully manicured shop assistants in turquoise cocktail dresses, with identical hair and physiques, followed a few steps behind us all the way round, pushing a shopping trolley in case we needed it.

I cannot say for sure from these experiences that there is an emerging North Korean middle class, but there are certainly more people on smartphones in the streets, more well-dressed locals in the shops and restaurants, and more taxis waiting for them outside.

Perhaps the most surprising first stirring of a consumer culture is that we also went to a Miniso. Miniso may not be well known in the west, but it is a giant of Chinese retail, big all over Asia. It is a low cost variety store selling household and consumer goods. In the past twelve months it has become the first and so far only foreign-branded retail outlet in the DPRK. That fact feels revolutionary. Just like everywhere else teenagers and twenty-somethings check themselves out in the mirrors before buying the latest fashions.

We noticed one other important change. Previously, the whole country was awash with massive billboards showing socialist-realist posters of soldiers charging into battle, of Stakhanovite workers building the country through blood, sweat and tears, emblazoned with messages of hatred of America. Tourists could readily buy copies from various specialist outlets and I have quite a collection at home.

However, this time we saw almost none. The billboards now show much softer images of farmers, scientists, teachers, mothers with children. We even saw one billboard near the airport advertising a car; another revolutionary development. And nowhere could we find any military images on posters to buy, even though we toured the Mansudae Studio where the propaganda artworks are all made. Our guides told us that is because Kim Jong Un is trying to play down the signs of warmongering while there is hope of diplomatic talks with the US.

There was a rather more relaxed attitude to photography this time too. Our guides saw me sneaking a few side shots of Kim statues but said nothing, and unlike before at no point did they ask to review, never mind delete, anything I took. The exception was at the Mass Games when I was gently asked not to take pictures when the mosaics of the Kims appeared, but even there I happily used a telephoto lens whereas before long-lenses were forbidden from the country.

Of course, the whole place feels like a mix of 1984 and the Truman Show and you can never be sure that what you have seen is real or true. But this time I also channelled Camberwick Green, Trumpton and Chigley, where simple folk lead simple lives cycling about trying to build their communities, though under the watchful eye of neighbours and officials who might report on them to the state.

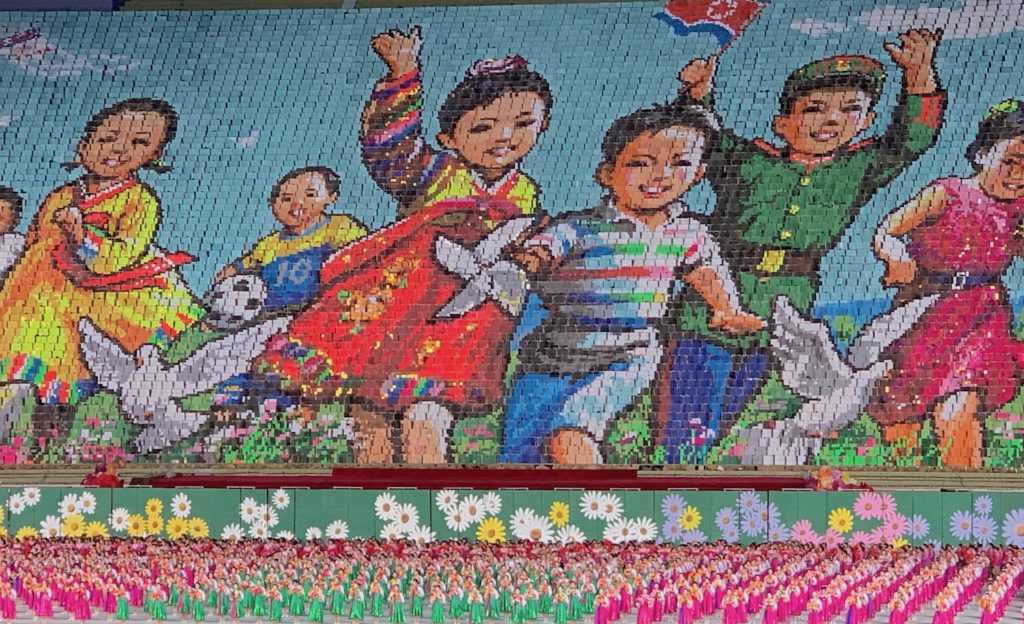

Mass Games

The unique North Korean Mass Games is socialist-realist performance art, a metaphor for the subservience of the individual to the collective, and conveying a propaganda narrative about the history of North Korea in the Kim era. It is also an unbelievable experience.

“Developing mass gymnastics is important in training schoolchildren to be fully developed communist people. To be a fully developed communist man, one must acquire a revolutionary ideology, the knowledge of many fields, rich cultural attainments and a healthy and strong physique. These are the basic qualities required of a man of the communist type. Mass gymnastics play an important role in training schoolchildren to acquire these communist qualities. Mass gymnastics foster particularly healthy and strong physiques, a high degree of organisation, discipline and collectivism in schoolchildren. The schoolchildren, conscious that a single slip in their action may spoil their mass gymnastic performance, make every effort to subordinate all their thoughts and actions to the collective.”

– Kim Il Sung

The annual Mass Games known as the Arirang Festival started in 2002 but was abolished by Kim Jong Un in 2013. It was brought back in an updated form in 2018. When we heard a few months ago that it would be staged again in 2019 – every night apart from Mondays between June and October – we immediately planned this trip around it.

The Mass Games is held in the May Day Stadium in central Pyongyang, the largest sports arena in the world, with a capacity of 150,000. Opened in 1989 as a statement response to Seoul hosting the Olympic Games in 1988, and renovated in 2015, its looping arches are impressive and visible all the way down the Taedong River, though you have to get closer to see the military motifs carved into the concrete.

There is no security check to get in, as it is obviously unnecessary, but surprisingly there is a merch stall, including great T-shirts.

Inside are two tiers of colourful seating. Both ends are empty as the small number of spectators are concertinad either side of the VIP green table that consumes most of one side. Tickets are priced for foreigners at €800 for a VIP seat, which we could see nobody took, €500 for first class, €300 for second class, and €100 for third class, which we were correctly informed are right next to the VIP section anyway.

The side opposite the VIP seats is given over to 18,000 people, each holding many different bits of coloured card that they move in perfect rhythm to keep changing a backdrop mosaic that can be seen from around the ground.

Proceedings begin with a massive North Korean flag ceremoniously marched in to the arena and raised high into the gantry. Then a huge team of drones are flown over the stadium, replicating the colours of the flag and then drawing Korean words in the sky. The highlights of the show are on the field, where tens of thousands of synchronised gymnasts perform for 90 minutes.

At one level this is a spectacle on a vast scale. At another level it is deeply controversial because of the alleged abuses of the gymnasts, especially children, who are made to miss school for ruthless training sessions over many months.

Just in front of us, there is a stage on which for twenty minutes in the middle of the show there are small scale dances. The stars of that section are definitely the soldiers who shatter concrete slabs with their bare hands in a karate chop.

This year’s production is called Land Of The Country and it tells the official story of North Korea since 1945 in three parts.

The first part, the liberation in 1945 through to winning the Korean War in 1953, is surprisingly short and ends with a mosaic of Kim Il Sung that triggers a rapturous standing ovation.

The second part tells a version of how the DPRK stood alone after the collapse of communism in Eastern Europe. It ends with a mosaic of Kim Jung Il.

The third, and much the longest, part portrays North Korea as it would like to be seen today, with plentiful food, a developing country built by teachers and scientists, with disco dancers in modern costumes. The mosaic of Kim Jong Un underscores the clear message that this country has been built by not two but three leaders.

The mosaic also reveals unsubtle messages, in English, about the need for “global independence”, “solidarity, co-operation, good neighbourliness”, and “multi-lateral foreign relations”.

The finale, to the tune of Guantanamera and then the national anthem, centres on two women on a giant stage in the middle, surrounded by hundreds of Korean flags waved vigorously, holding hands in a symbolic craving for the reunification of Korea.

At the zoo

We were supposed to go to the botanical gardens, half an hour outside Pyongyang, on the way to the Memorial for North Koreans who fought Japan in WWII. When we got there, in a totally unexpected and spontaneous development, our guides suddenly declared that they wanted to abandon the schedule meticulously negotiated months before as they would prefer to go to the zoo, which is right opposite. We leapt at the chance. It turned out to be very revealing.

The entrance is through the giant mouth of a tiger, and we immediately felt like exhibits ourselves as villagers and schoolchildren unused to foreigners were more interested in staring at us than the animals.

Throughout the zoo, there are many signposts explaining which Asian politicians donated which animals. For instance, Ho Chi Minh apparently contributed an elephant in 1959. Most were of course given by Kim Jong Un, including English Pointers. Yes, in the zoo there are domestic dogs, Irish setters, cocker spaniels, poodles and pekingese, creatures all familiar with human company.

The other shock is that people are encouraged to feed the animals. Bread rolls are handed to elephants, popcorn is thrown at hippos, and ice cream in its plastic containers is thrown at bears, making them beg on two feet.

On the farm

One of the most common questions I am asked about North Korea is: what is the food like? There was of course widespread shortages and starvation in the years after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, and North Koreans are famous for eating dogs, which you can choose from the menus in select restaurants, as we did.

We were taken to the Jangchon Vegetable Farm Collective, near the Taedonggang brewery to the east of Pyongyang. Apart from the huge mosaic of Kim Il Sung standing with farmers in a field, at first sight the buildings look modern enough. We were shown to the nursery where the farmers’ young children were singing, and we saw the farmers’ health club, with a huge photo of Kim Jong Un at the entrance. But we saw no actual farmers; we were told they had all gone to the Film Festival for the day.

Each family in North Korea is allocated a fixed ration of fruit and veg more or less for free that is delivered to their homes every week, with a little extra on special occasions such as Kim Il Sung’s birthday. This is a far cry from the cuisine we experienced in the swanky restaurants which were mostly filled with what looked like middle class locals.

Barley tea and Taedonggang beer are popular with every meal. Barbecue, bibimbap, hotpot, Chinese, Japanese and other Asian foods are all common, as of course is kimchi and similar small spicy dishes, followed by rice to finish. The local favourite is the excellent raengmyon, Pyongyang Cold Noodles, with vegetables and mustard, especially from Okryugwan, the historic restaurant that even has a branch in Indonesia and used to have one in Dubai too.

We were taken to outstanding restaurants, mostly divided into small rooms which were full of locals; but we were unable to tell how many people were in other rooms. On our previous visit we had set meals, but this time we were able to order from menus at roughly €10 a head, and we bought for our guides and driver who always insisted on eating at the same table with us.

Taedonggang Seafood Restaurant has very large pools of very large fish swimming about that can be selected for cooking. We were shown to the very table at which last year Kim Jong Un hosted Moon Jae In, President of South Korea. There are great views of the Mansudae statues of the first two Kims across the river, though our reverie was disturbed by cruelty when we were served with a still-breathing sturgeon, despite the fact that its body had been sliced into sashimi and we had just drunk its blood with a local liqueur.

***

There is no doubt that there is a moral dilemma in choosing to travel in an authoritarian country where people are so oppressed and so poor and you know you are going to be presented only with a propagandised version of how things are. I am under no illusions that we saw very little of whatever there is of the real Pyongyang.

But apart from the awesome spectacle of the Mass Games, there is real value to understanding how the North Korean regime wants foreigners to see their country, in glimpsing aspects of life that here would be called normal but to me felt bizarre, and in calibrating the changes of the past three years, a time when the DPRK is never far from the international headlines.

These tours are packed with incident and experiences: drinking local beer in a bar; firing rifles and pistols at a popular shooting range; attending a performance in the Opera House, apparently the greatest hits from five revolutionary operas written by Kim Jung Il himself; joining a cruise down the Taedong with introverted North Koreans, a drunken Chinese tour party and a brave Japanese couple. Our guides worked hard to keep us from sitting still, to show us as much as possible or to stop us becoming too inquisitive.

It feels so sad to leave, much more so than other countries. Knowing we are leaving behind our guides, and 25 million people, to a life of unfulfilled potential. Gamsahabnida.